Artificial intelligence thrives on data. The more diverse and granular the data, the better the model. However, this voracious appetite for information often collides with a fundamental human right: privacy. In an era of stringent data protection laws like GDPR and increasing user awareness regarding digital surveillance, the traditional method of centralizing massive datasets to train AI models is becoming risky and, in some cases, obsolete.

Enter privacy-preserving AI. This is not a single tool, but a suite of techniques designed to allow machine learning models to learn from sensitive data without ever actually “seeing” the raw information.

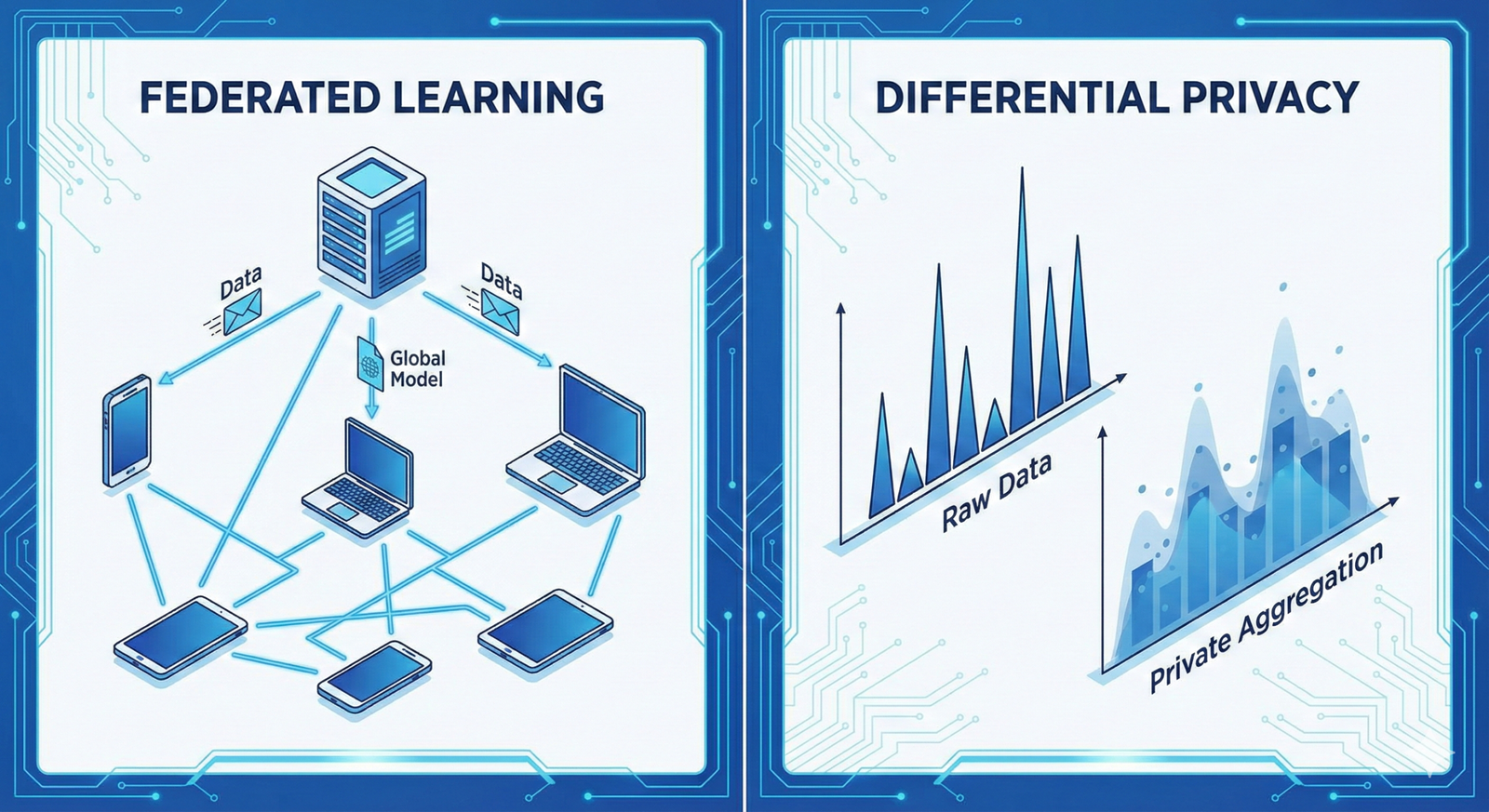

In this guide, “privacy-preserving AI” refers specifically to the architectural and mathematical techniques—primarily Federated Learning (FL) and Differential Privacy (DP)—that enable model training and inference while mathematically guaranteeing the confidentiality of individual data points.

Key Takeaways

- Decentralization is Key: Federated Learning moves the training to the data, rather than moving the data to the training.

- Noise is Protection: Differential Privacy adds calculated “noise” to data or model updates so that no single individual’s contribution can be reverse-engineered.

- Beyond Anonymization: Traditional data masking (removing names/IDs) is insufficient against modern AI reconstruction attacks; mathematical guarantees are required.

- The Trade-off: There is almost always a trade-off between the level of privacy (epsilon) and the utility (accuracy) of the model.

- Composite Security: These technologies work best when layered. FL keeps data local, while DP protects the updates sent from the local device to the central server.

Who This Is For (And Who It Isn’t)

This guide is designed for data scientists, privacy engineers, technical product managers, and compliance officers who need to understand the architecture and application of privacy-preserving machine learning (PPML). It assumes a basic familiarity with how machine learning models are trained (data inputs -> training -> model weights) but does not require a PhD in cryptography.

This is not a legal compliance manual. While we discuss regulations like GDPR in the context of technology, this guide does not constitute legal advice regarding data sovereignty or compliance certification.

1. The Core Problem: Why Traditional AI Training is Vulnerable

To understand the solution, we must first dissect the problem. In a traditional centralized AI workflow, data is collected from users (via smartphones, browsers, IoT devices), encrypted in transit, and stored in a central data lake. The AI model is then trained on this aggregate data.

While encryption protects data from hackers during transmission, the privacy risk emerges during the computation and training phase.

The Fallacy of Anonymization

For years, companies relied on “anonymization” or “de-identification”—stripping Personally Identifiable Information (PII) like names and social security numbers from datasets. However, research has repeatedly shown that in high-dimensional datasets, individuals can be re-identified using metadata.

For example, knowing a user’s approximate location, gender, and birth year is often enough to uniquely identify them within a dataset. When AI models memorize these patterns, they can inadvertently regurgitate sensitive data.

Model Inversion and Membership Inference

The threats to AI privacy are active and sophisticated. Two primary attack vectors highlight why we need advanced techniques:

- Membership Inference Attacks (MIA): An attacker queries a trained model and, based on the confidence of the model’s output, can determine whether a specific individual’s data was used to train that model. In healthcare, knowing a person was in a “cancer patient database” violates privacy, even if their specific medical records aren’t revealed.

- Model Inversion Attacks: An attacker reverses the model’s learning to reconstruct the original input data. For example, researchers have successfully reconstructed recognizable images of faces solely by querying facial recognition systems.

These vulnerabilities necessitate a shift from “security by policy” (promising not to look at the data) to “security by design” (mathematically preventing the data from being seen).

2. Federated Learning: Bringing the Code to the Data

Federated Learning (FL) is the architectural pillar of privacy-preserving AI. Introduced largely by Google in 2017 (originally for predictive text on Android keyboards), it fundamentally flips the standard machine learning workflow.

How It Works: The Baker Analogy

Imagine a bakery franchise trying to perfect a cookie recipe.

- Centralized approach: Every franchise sends their ingredients to a central headquarters. The HQ bakes thousands of cookies, tweaks the recipe, and sends the final recipe back. This is risky because the ingredients (data) leave the local shops.

- Federated approach: The HQ sends a draft recipe to all franchises. Each franchise buys its own ingredients and bakes a batch locally. They don’t send the ingredients to HQ; they only send a report saying, “Ideally, bake it 2 minutes longer and add 5% more sugar.” HQ averages these thousands of reports to update the master recipe.

In technical terms:

- Initialization: A central server initializes a global model (neural network).

- Broadcast: The server sends the current model weights to a selection of eligible client devices (edge devices like phones, or silos like hospitals).

- Local Training: Each client trains the model on its own local, private data.

- Aggregation: The clients compute the “update” (the gradient, or how much the weights should change) and send only the update back to the server. The raw data never leaves the device.

- Global Update: The server averages these updates (using algorithms like Federated Averaging or FedAvg) to improve the global model.

- Iteration: The process repeats.

Types of Federated Learning

In practice, FL is categorized by the nature of the participants:

Cross-Device Federated Learning

- Participants: Millions of mobile or IoT devices.

- Characteristics: Devices are unreliable (batteries die, WiFi drops), have limited compute power, and data is not identically distributed (one user types differently than another).

- Use Case: Predictive text, voice recognition improvements (Siri/Google Assistant), health metrics on wearables.

Cross-Silo Federated Learning

- Participants: A small number of reliable, high-power entities (e.g., 10 hospitals or 5 banks).

- Characteristics: High availability, massive local datasets, legal contracts binding the participation.

- Use Case: Financial fraud detection across competing banks; training rare disease models across hospitals without sharing patient records.

The Limits of Federated Learning

While FL ensures raw data doesn’t cross the network, it is not a silver bullet. The gradient updates sent back to the server can still leak information. If a specific user has very unique data, their “update” to the model might look drastically different from everyone else’s, allowing the server to infer their private data points.

This is why Federated Learning is rarely used alone. It is almost always paired with Differential Privacy.

3. Differential Privacy: The Mathematics of Plausible Deniability

Differential Privacy (DP) is the mathematical standard for privacy guarantees. It addresses the question: “How much information about an individual is leaked by the output of a computation?”

The Core Concept: The “Noise” Mechanism

To understand DP, imagine you are conducting a survey asking people a sensitive question: “Have you ever committed a crime?”

If people answer truthfully, they risk exposure. To protect them, you use a randomized response mechanism:

- Flip a coin.

- If distinct heads, answer truthfully.

- If tails, flip a second coin.

- If heads, answer “Yes.”

- If tails, answer “No.”

When you collect the data, you will see many “Yes” answers. However, you cannot know if any specific “Yes” is a confession or just a random coin flip. This gives the respondent plausible deniability. Yet, because you know the probability of the coin flips (50/50), you can statistically estimate the true percentage of crime in the population by subtracting the expected noise.

In AI, we don’t flip coins, but we inject statistical noise (typically Laplacian or Gaussian noise) into the data or the model gradients.

Epsilon (ϵ): The Privacy Budget

The strength of differential privacy is measured by a parameter called Epsilon (ϵ), often referred to as the privacy budget.

- Low Epsilon (e.g., ϵ = 0.1): High noise, high privacy, lower data utility. The data is very “fuzzy.”

- High Epsilon (e.g., ϵ = 10): Low noise, lower privacy, higher data utility. The data is clearer but riskier.

Managing the privacy budget is one of the hardest parts of implementing DP. Every time you query the data or train an epoch, you “spend” some of your privacy budget. Once the budget is exhausted, you must stop using that data, or the risk of re-identification becomes mathematically unacceptable.

Local vs. Global Differential Privacy

There are two main places to add the noise:

- Local Differential Privacy (LDP): Noise is added on the user’s device before the data ever leaves.

- Pro: The server never sees the real data. Even if the server is malicious, the user is safe.

- Con: Requires a lot of noise to be effective, which can severely degrade model accuracy.

- Example: Apple collecting emoji usage statistics from iPhones.

- Global (Central) Differential Privacy: The server collects clean data (or clean updates) in a secure environment, aggregates them, and then adds noise to the output.

- Pro: Requires less noise for the same level of accuracy.

- Con: You must trust the server (the aggregator) to be honest and secure.

4. The Power Couple: Combining FL and DP

The modern standard for privacy-preserving AI involves combining these two technologies.

In a Federated Learning system with Differential Privacy:

- The client trains the model locally (FL).

- The client clips the weight updates (limiting how much influence one person can have).

- The client (or a secure aggregator) adds noise to the updates (DP).

- The noisy updates are sent to the server.

This architecture ensures that the server receives an update that is statistically useful for learning patterns but contains no mathematically recoverable information about any single user.

Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC)

Often, a third layer is added: Secure Multi-Party Computation. This allows the server to aggregate the updates from users without seeing the individual updates at all.

Think of it like calculating the average salary of a group of friends without anyone revealing their salary.

- Person A adds a random number to their salary and passes it to Person B.

- Person B adds their salary and passes it to Person C.

- Person C adds their salary…

- The final sum is returned to the group, and the random number is subtracted.

- The group knows the total (and average), but nobody knows what the others earn.

In AI, SMPC (using protocols like Secure Aggregation) ensures the central server sees only the final averaged model update, not the specific updates from User A or User B.

5. Other Key Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs)

While FL and DP are the heavy lifters, other technologies play vital roles in the ecosystem.

Homomorphic Encryption (HE)

Homomorphic encryption allows computational operations to be performed on encrypted data without decrypting it first.

- The Magic: You can take encrypted number A and encrypted number B, multiply them, and the result (when decrypted) is A×B.

- The Catch: It is incredibly computationally expensive. As of 2026, fully homomorphic encryption (FHE) is typically too slow for training large neural networks but is increasingly used for inference (running a query on a model without revealing the query to the model owner).

Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs)

TEEs (or Enclaves) are hardware-based security features (like Intel SGX or ARM TrustZone). They create a “black box” within a computer’s processor. Data is decrypted only inside this hardware vault, processed, and then re-encrypted before leaving. TEEs provide a hardware guarantee that even the system administrator or cloud provider cannot peek at the data during processing.

6. Real-World Use Cases and Industry Adoption

Privacy-preserving AI is moving rapidly from research labs to production environments.

Healthcare: Collaborative Diagnostics

Hospitals possess valuable datasets (e.g., MRI scans for tumor detection) but cannot share them due to HIPAA or GDPR.

- Application: Using Cross-Silo Federated Learning, ten hospitals can collaborate to train a single, superior tumor-detection model. The model travels to each hospital, learns from the local X-rays, and moves on (or sends updates back).

- Result: A model trained on 100,000 diverse patients without a single medical record leaving the hospital premises.

Finance: Anti-Money Laundering (AML)

Banks are required to detect money laundering, but criminals often hide by moving money between different banks. Banks cannot simply share all transaction histories with competitors.

- Application: Privacy-preserving set intersection and FL allow banks to identify suspicious patterns across institutions. If a user exhibits risky behavior at Bank A and Bank B, the joint model can flag the risk score without Bank A revealing its client list to Bank B.

Smart Devices: Predictive Features

- Application: Smartphone keyboards (Gboard, iOS QuickType) use Federated Learning to learn new slang words or typing habits.

- Result: The keyboard gets smarter for everyone (“autocorrecting” new trending words) without Google or Apple reading your text messages.

7. Implementation: A Guide to the Stack

If you are an engineer or data scientist looking to implement this, the ecosystem has matured significantly. You no longer need to write cryptographic primitives from scratch.

Leading Libraries and Frameworks

- TensorFlow Federated (TFF):

- Owner: Google

- Focus: Simulation and research of FL algorithms. It allows you to simulate millions of clients on a single machine to test convergence.

- Best for: Prototyping FL architectures.

- PySyft:

- Owner: OpenMined (Open Source Community)

- Focus: A comprehensive library for remote data science. It integrates with PyTorch and allows you to perform FL, SMPC, and DP.

- Best for: Education and building privacy-preserving pipelines from the ground up in Python.

- Opacus:

- Owner: Meta (Facebook)

- Focus: High-speed Differential Privacy for PyTorch. It allows you to train PyTorch models with DP guarantees with minimal code changes.

- Best for: Adding Differential Privacy to existing centralized training pipelines.

- NVIDIA FLARE (Federated Learning Application Runtime Environment):

- Owner: NVIDIA

- Focus: Enterprise-grade FL, particularly strong in medical imaging and cross-silo setups.

- Best for: Real-world deployment in healthcare and finance.

Step-by-Step Implementation Strategy

Phase 1: Definition & Simulation

- Define the privacy threat model. Who is the adversary? (The server? The other clients? An external hacker?)

- Select the architecture (Cross-silo vs. Cross-device).

- Simulate the environment using TensorFlow Federated to ensure the model converges. FL models often take longer to converge than centralized ones.

Phase 2: Privacy Budgeting

- Determine the acceptable ϵ (epsilon). This is often a policy decision, not just technical.

- Use libraries like Opacus to measure the privacy loss over training epochs.

- Implement “Gradient Clipping” to limit the impact of outliers.

Phase 3: Deployment & Orchestration

- For cross-device, you need an orchestration server that handles device availability (handling dropouts is critical).

- Implement Secure Aggregation to protect the updates in transit.

- Monitor model performance metrics separately for different demographic groups to ensure the “noise” of DP hasn’t disproportionately affected underrepresented groups (bias check).

8. Challenges and Limitations

Despite the promise, privacy-preserving AI is difficult to implement correctly.

The Accuracy Trade-off

There is no free lunch. Adding noise (DP) creates a fuzzier view of reality.

- Impact: A model trained with strict privacy guarantees (low epsilon) will almost always be less accurate than a model trained on raw data.

- Mitigation: Engineers must find the “sweet spot” where privacy is sufficient and accuracy is acceptable. This often requires larger datasets to compensate for the noise.

System Heterogeneity

In cross-device FL, one user might have an iPhone 16 Pro, and another a five-year-old budget Android.

- Impact: The powerful phone finishes training in seconds; the old phone takes minutes or crashes. If you only wait for the fast phones, your model becomes biased toward wealthy users.

- Mitigation: Asynchronous aggregation protocols and intelligent client selection algorithms are required to ensure fair representation.

“Privacy Washing”

Just because a company uses Federated Learning does not mean they are private. If they do not use Differential Privacy or Secure Aggregation, the updates can still leak user data. Similarly, setting a meaningless privacy budget (e.g., ϵ = 100) provides a false sense of security with no actual mathematical protection.

9. Regulatory Context: GDPR, AI Act, and Beyond

Privacy-preserving AI is not just a technical feature; it is a compliance strategy.

GDPR (Europe): The General Data Protection Regulation emphasizes “Data Minimization” (collecting only what is needed). Federated Learning aligns perfectly with this by minimizing data transfer. However, the “Right to Explanation” and “Right to be Forgotten” become complex in FL. If a user withdraws consent, how do you “unlearn” their contribution from a global model that has already been aggregated? This remains an active area of research (Machine Unlearning).

EU AI Act: As of 2026, the EU AI Act classifies certain AI systems as high-risk. Using privacy-preserving techniques demonstrates a commitment to risk mitigation and robust governance, which can smooth the path to regulatory approval for sensitive applications (like credit scoring or biometric identification).

10. Future Trends: The Road Ahead

As we look toward the latter half of the 2020s, privacy-preserving AI is evolving.

1. Synthetic Data

Rather than just protecting real data, we are seeing a surge in Synthetic Data generation. Companies use a small amount of real data (protected by DP) to train a generator, which then creates infinite “fake” data that statistically resembles the real data. This synthetic data can be shared openly without privacy risks.

2. Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) in AI

ZKPs allow a party to prove they know something (or that a computation was done correctly) without revealing the data itself. We expect to see ZKPs used to verify that a client in a Federated Learning system actually ran the model correctly and didn’t just send malicious noise, all without the server seeing the data.

3. Edge AI and Personal Agents

With the rise of “Agentic AI” (personal AI assistants), privacy will move even closer to the user. We will see “Personal Large Language Models” (PLLMs) that run entirely on-device (laptop/phone), fine-tuned on the user’s emails and documents using FL, ensuring that the personal context never leaves the local machine.

Conclusion

Privacy-preserving AI represents a fundamental shift in the social contract of technology. It proves that we do not have to choose between smart technology and personal privacy—we can, with significant engineering effort, have both.

Federated Learning allows us to unlock the intelligence trapped in silos, while Differential Privacy provides the mathematical shield that builds trust. For organizations, adopting these technologies is no longer just a “nice to have”—it is becoming a prerequisite for operating in a data-conscious world.

Next Steps for Implementation:

- Audit your data: Identify which datasets are currently siloed or unused due to privacy concerns.

- Pick a pilot: Choose a low-risk use case (e.g., internal analytics or predictive maintenance) to test a Federated Learning framework.

- Define your budget: Not the financial budget, but your privacy budget (ϵ). Engage legal and data teams to agree on acceptable risk levels.

The future of AI is distributed, private, and secure.

FAQs

1. Does Federated Learning guarantee privacy on its own?

No. Federated Learning prevents raw data from leaving the device, which is a massive privacy improvement. However, without Differential Privacy, the model updates sent to the server can theoretically be reverse-engineered to reveal inputs. FL is the architecture; DP is the guarantee.

2. What is a “good” value for Epsilon (ϵ) in Differential Privacy?

There is no universal standard, but generally, single-digit values are preferred. Academic literature often targets ϵ<1, while widely deployed industrial systems (like those from Apple or Google) have historically used values between 2 and 8 (or sometimes higher). A lower number means stronger privacy.

3. Will privacy-preserving AI make my model less accurate?

Yes, typically. Adding noise (DP) or training on heterogeneous devices (FL) usually results in a slight drop in accuracy compared to training on a perfectly centralized, raw dataset. The goal is to maximize the “privacy-utility trade-off,” accepting a small accuracy loss for a massive gain in security and compliance.

4. Can I use Federated Learning for Large Language Models (LLMs)?

Yes, this is known as Federated Fine-Tuning. While training a massive LLM (like GPT-4) from scratch via FL is currently computationally impractical for edge devices, fine-tuning a pre-trained model on local user data (e.g., adapting a coding assistant to a company’s private codebase) is a prime use case for FL.

5. Is “anonymized” data the same as “privacy-preserving” data?

No. Anonymization (removing names/IDs) is a weak protection that can often be reversed via linkage attacks (combining the data with public records). Privacy-preserving techniques like Differential Privacy provide mathematical guarantees that resist these reconstruction attacks.

6. Does this comply with GDPR?

Privacy-preserving techniques heavily support GDPR compliance, specifically the principles of Data Minimization and Privacy by Design. However, using these tools does not automatically grant compliance. You still need legal bases for processing, consent mechanisms, and governance frameworks.

7. What is the difference between SMPC and Federated Learning?

Federated Learning is a machine learning approach (how we train). Secure Multi-Party Computation (SMPC) is a cryptographic technique (how we compute). They are often used together: FL determines what to calculate (model updates), and SMPC determines how to aggregate those updates so the server can’t see the individual contributions.

8. Is Homomorphic Encryption ready for production AI?

For training? generally no—it is too slow. For inference? Yes. It is increasingly used to allow a client to send encrypted data to a cloud model, have the model process it encrypted, and return an encrypted result, ensuring the cloud provider never sees the user’s query.

9. What are “Data Clean Rooms”?

Data Clean Rooms are secure environments where two parties (e.g., a retailer and an advertiser) can match their data to find common customers without either party seeing the other’s raw list. They often use technologies like SMPC and Differential Privacy to facilitate this “blind” collaboration.

10. Can I implement this on existing cloud infrastructure (AWS/Azure)?

Yes. Major cloud providers are integrating these tools. AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud offer trusted execution environments (Confidential Computing) and support frameworks like NVIDIA FLARE or TensorFlow Federated that can run on their infrastructure.

References

- Google AI. (2017). Federated Learning: Collaborative Machine Learning without Centralized Training Data. Google AI Blog. https://ai.googleblog.com/2017/04/federated-learning-collaborative.html

- Dwork, C., & Roth, A. (2014). The Algorithmic Foundations of Differential Privacy. Foundations and Trends in Theoretical Computer Science. https://www.cis.upenn.edu/~aaroth/Papers/privacybook.pdf

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). (2025). Privacy-Enhancing Technologies: An Introduction to Differential Privacy. NIST Cybersecurity White Paper. https://www.nist.gov/

- Apple. (2023). Learning with Privacy at Scale. Apple Machine Learning Research. https://machinelearning.apple.com/research/learning-with-privacy-at-scale

- McMahan, B., et al. (2017). Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. AISTATS 2017. https://arxiv.org/abs/1602.05629

- OpenMined. (2024). PySyft: A Library for Encrypted, Privacy Preserving Machine Learning. OpenMined Documentation. https://github.com/OpenMined/PySyft

- Meta AI. (2023). Opacus: High Speed Differential Privacy for PyTorch. https://opacus.ai/

- European Commission. (2026). The EU AI Act: Regulatory Framework for Artificial Intelligence. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai

- Kaissis, G. A., et al. (2020). Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging. Nature Machine Intelligence. https://www.nature.com/articles/s42256-020-0186-1

- IEEE Standards Association. (2024). IEEE Standard for Federated Machine Learning. IEEE P3652.1. https://standards.ieee.org/