Space is vast, hostile, and incredibly distant. For decades, space exploration relied on a tight tether to Earth: human operators in control rooms painstakingly sending commands and waiting minutes, or even hours, for a response. Today, that paradigm is shifting. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is cutting the tether, allowing spacecraft to think, navigate, and survive on their own.

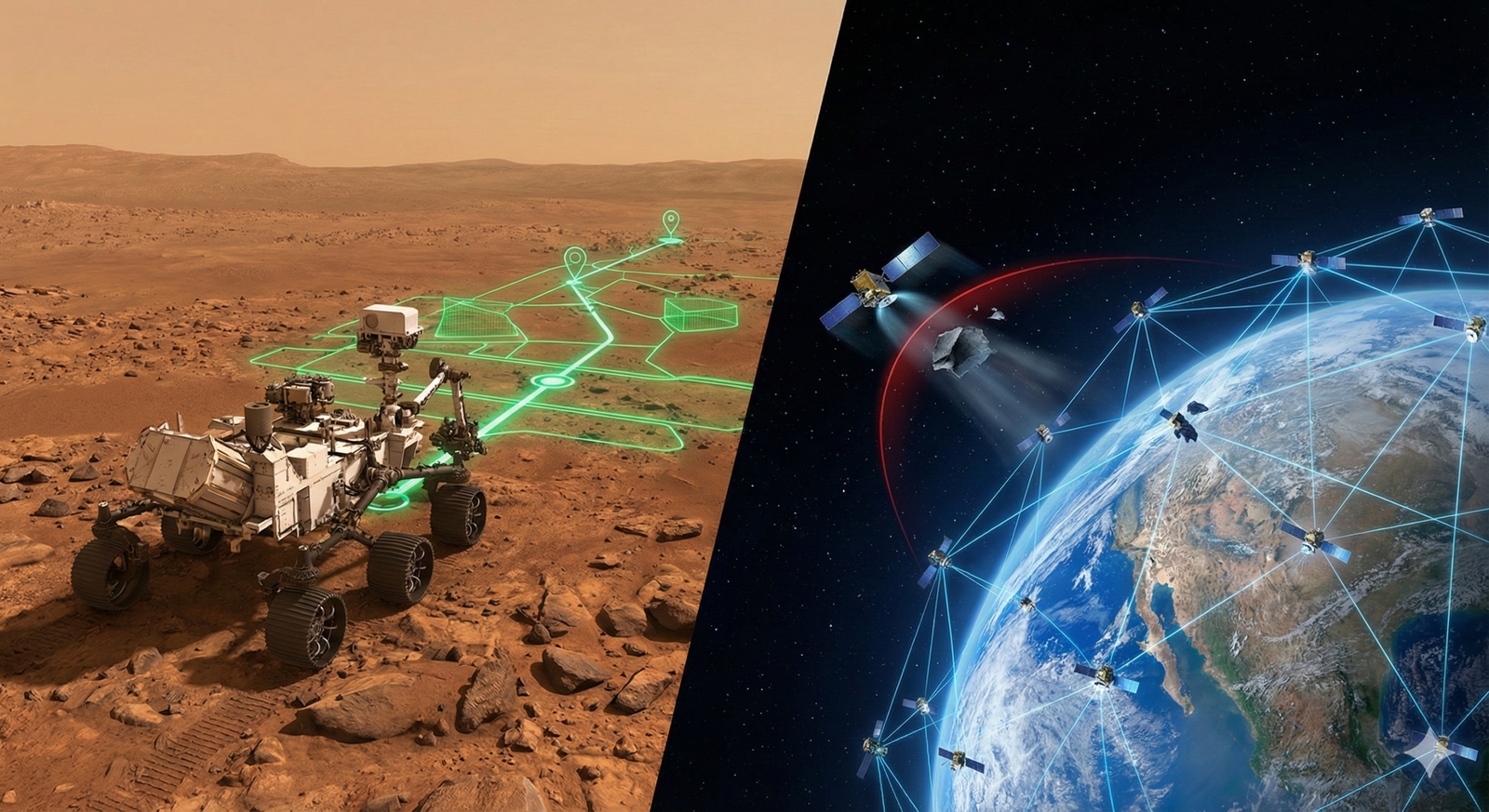

AI in space exploration is no longer a futuristic concept; it is the operational backbone of modern missions. From the Red Planet’s dusty surface to the crowded orbits of Low Earth Orbit (LEO), machine learning and autonomous systems are managing tasks that are too fast, too complex, or too remote for humans to handle in real-time.

Key Takeaways

- Latency is the driver: AI is essential because light-speed delays make real-time human control of deep-space assets impossible.

- Autonomy saves missions: Autonomous navigation allows rovers and probes to avoid hazards instantly without waiting for Earth’s permission.

- Orbit is crowded: AI is the only scalable solution for managing traffic and avoiding collisions in mega-constellations of thousands of satellites.

- Data filtering is crucial: “Edge AI” processes data on the spacecraft, sending back only scientific discoveries rather than terabytes of empty space.

- The future is swarms: Upcoming missions will utilize swarms of small, AI-driven satellites working in unison, rather than single large monoliths.

In this comprehensive guide, “AI” refers to the suite of technologies including machine learning (ML), computer vision, and autonomous planning systems used to operate space assets. This analysis covers the technical mechanisms, the critical applications in orbit and deep space, and the significant challenges that remain.

The Necessity of Autonomy: Why Humans Can’t Drive

To understand why AI is mandatory in space, one must first understand the tyranny of distance. The speed of light is fast (approximately 300,000 kilometers per second), but space is enormous.

The Latency Problem

When a Mars rover faces a cliff edge, it cannot wait for a human driver to hit the brakes.

- Moon: ~1.3 seconds one-way light time (manageable delay).

- Mars: Between 3 and 22 minutes one-way. A command sent “now” arrives 20 minutes later; the confirmation takes another 20 minutes to return.

- Outer Planets: Hours of delay.

If a spacecraft encounters a critical anomaly during a maneuver—such as the “Seven Minutes of Terror” during a Mars landing—it must react in milliseconds. A human operator on Earth is effectively a historian, watching events that happened minutes ago. AI provides the on-board capability to assess state, detect faults, and execute contingency plans instantly.

The Data Bandwidth Bottleneck

We are launching sensors capable of capturing 4K video and hyperspectral imagery, yet our “internet connection” to space (the Deep Space Network) is akin to a dial-up modem from the 1990s for many deep-space missions. AI solves this by analyzing data in situ, discarding the noise, and transmitting only the signal.

Autonomous Spacecraft: How Robots Navigate the Unknown

Autonomous spacecraft are vehicles capable of executing complex tasks without real-time human intervention. This is most visible in planetary rovers and deep-space probes.

Visual SLAM and Terrain Relative Navigation

How does a robot know where it is on a planet with no GPS? It uses a technique called Visual SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping).

- Perception: The rover’s cameras take rapid photos of the surrounding terrain.

- Feature Extraction: The AI identifies distinct features (sharp rocks, crater rims, dune edges).

- Tracking: As the rover moves, it tracks how these features shift in its field of view.

- Mapping: It builds a 3D map of its surroundings while simultaneously calculating its own position within that map.

NASA’s Perseverance rover uses a system called AutoNav. Unlike its predecessor Curiosity, which often had to stop and wait for Earth to plan its path, Perseverance can “think while driving.” It generates maps of the terrain ahead, identifies hazards (sand traps, high slopes), and calculates the safest, most efficient route—all while moving. This has drastically increased the speed of exploration, allowing the rover to cover more ground in a month than previous rovers covered in a year.

Hazard Detection and Avoidance (HDA)

During the landing phase of modern missions, AI is the pilot. Terrain Relative Navigation (TRN) allows a descending spacecraft to photograph the landing site, compare it to an onboard orbital map, and identify a safe landing spot free of boulders or slopes. If the primary site looks dangerous, the AI diverts the craft to a safer target within seconds. This technology was critical for the successful landing of the Mars 2020 mission in Jezero Crater, a site previously deemed too hazardous for unguided landings.

Satellite Management: AI Traffic Control in Low Earth Orbit

While deep space requires autonomy due to distance, Earth orbit requires autonomy due to density. We are in the era of “New Space,” characterized by the launch of mega-constellations like Starlink, OneWeb, and Kuiper.

The Congestion Crisis

As of January 2026, the number of active satellites in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) has skyrocketed into the tens of thousands. Human operators can no longer manually plot the orbits of every object to check for collisions. The “conjunction alerts” (warnings of close approaches) are becoming too frequent for manual review.

Autonomous Collision Avoidance

Satellite management is shifting from ground-based control to on-board autonomy.

- The Old Way: Ground radar tracks debris. A computer on Earth calculates a probability of collision. An operator reviews the data. A command is uploaded to the satellite to fire thrusters.

- The AI Way: Satellites constantly share their position and trajectory data with each other and ground stations. On-board AI algorithms evaluate collision risks in real-time. If a probability threshold is crossed, the satellite autonomously calculates a “slew” (maneuver) to duck out of the way and return to its original orbit, notifying Earth only after the safety maneuver is complete.

This level of satellite constellation traffic management is the only way to prevent the Kessler Syndrome—a theoretical scenario where a collision creates debris that causes further collisions, eventually rendering LEO unusable.

Formation Flying and Swarms

AI enables satellites to fly in tight formations, acting as a single, large instrument. For example, a swarm of small satellites could arrange themselves to form a giant telescope mirror. To do this, they must maintain precise relative distances. AI control loops adjust thrusters dynamically to compensate for atmospheric drag or gravitational anomalies, keeping the swarm in perfect sync without constant ground instruction.

Space Debris Monitoring: Tracking the Invisible

Space is filled with junk: spent rocket stages, dead satellites, and paint flecks traveling at 17,500 miles per hour. Space debris monitoring is a data problem of massive scale.

Machine Learning for Object Detection

Ground-based radar and optical telescopes generate petabytes of noisy data. Distinguishing a piece of debris from cosmic noise, a star, or a glitch is difficult.

- Deep Learning Models: AI models are trained on historical radar data to recognize the “signature” of debris. They can identify new objects faster and with higher accuracy than traditional statistical methods.

- Orbit Prediction: Predicting where a tumbling, irregular piece of metal will be in three days is complex due to fluctuating atmospheric drag (affected by solar activity). Neural networks can analyze years of orbital decay data to learn these complex patterns, providing more accurate “conjunction” (collision) warnings.

In-Orbit Debris Removal

Future missions aim to actively remove debris. This requires a “chaser” satellite to approach a tumbling, non-cooperative target (a dead satellite). This is an extreme robotics challenge. The chaser must use computer vision to understand the rotation of the target and match its spin perfectly to capture it. This maneuver requires high-frequency, autonomous control loops that only AI can provide.

On-Board Data Processing: Edge AI in Orbit

Historically, satellites were “dumb” data collectors. They snapped photos and radioed them down to Earth for processing. This is inefficient.

The Cloud vs. The Edge

In the context of space, “The Edge” is the satellite itself. Onboard data processing involves putting AI chips (like FPGAs or specialized ASICs) directly on the spacecraft.

Use Case: Earth Observation

Consider a satellite monitoring deforestation or illegal fishing.

- Without AI: The satellite takes 1,000 photos. 600 of them are covered in clouds. It transmits all 1,000 photos to Earth. This consumes massive power and bandwidth.

- With AI: A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) on the satellite analyzes the photos instantly. It detects that 600 are cloudy and deletes them. It identifies illegal trawlers in 5 images and marks them as “High Priority.” It transmits only the clear, relevant images to Earth.

This capability reduces the “time-to-insight” from days to minutes. In disaster response (e.g., wildfires or floods), this speed saves lives.

ESA’s Φ-sat-1 Experience

The European Space Agency (ESA) demonstrated this with the Φ-sat-1 (Phi-Sat-1) mission, which carried an AI chip specifically to filter out cloudy images. This marked the beginning of “Smart Satellites” that act as intelligent agents rather than passive cameras.

NASA AI Initiatives and Global Efforts

Major space agencies are investing heavily to integrate AI into every layer of mission architecture.

NASA’s Cognitive Radio and Communications

The electromagnetic spectrum is crowded. NASA is developing “cognitive radios” that use AI to analyze the radio environment and switch frequencies or modulation schemes on the fly to avoid interference and maximize data throughput. This optimizes the use of the Deep Space Network (DSN), ensuring that precious antenna time is not wasted.

The Search for Life (Exoplanets)

Finding a planet around another star involves analyzing dips in light (transit method). Machine learning in space science is used to sift through data from telescopes like TESS and Kepler. AI models can detect subtle patterns in light curves that human astronomers might miss, identifying potential exoplanet candidates and classifying them by habitability potential.

ESA’s “Digital Twin” Earth

The ESA is using AI to create a “Digital Twin” of Earth—a dynamic, digital replica of the planet fueled by satellite data. AI models simulate atmosphere, ocean, and ice interactions to predict climate impacts with unprecedented precision.

Deep Space & Interstellar Concepts

As we look beyond Mars, AI becomes the captain of the ship.

The AI Astronaut Assistants

In movies, we have HAL 9000 (a cautionary tale) and TARS. In reality, we have CIMON (Crew Interactive Mobile Companion). Used on the International Space Station, CIMON is an AI-powered floating sphere that helps astronauts with procedures. It can display manuals, record experiments, and answer voice queries. In deep space missions to Mars, communication with Earth will be too slow for troubleshooting. An onboard AI assistant will act as the repository of all mission knowledge, helping astronauts diagnose system failures or medical emergencies without calling Houston.

Self-Healing Systems

Deep space probes must be resilient. “Self-healing” systems use AI to detect component degradation. If a reaction wheel starts vibrating abnormally, the AI could proactively shift the load to a backup wheel or alter the spacecraft’s control laws to compensate, extending the mission life.

Common Mistakes and Misconceptions

When discussing AI in space, it is easy to fall into science fiction tropes. Here is a reality check on common pitfalls.

1. “AI Controls Everything”

Reality: Mission control is still king. While AI handles immediate navigation and safety, strategic decisions (e.g., “Where should we drive next week?” or “Should we change the mission goals?”) are still made by human scientists. AI is a tool for execution, not high-level strategy.

2. “Space AI is the same as Earth AI”

Reality: You cannot just put an NVIDIA gaming GPU in space. Space has high radiation which flips bits in computer memory (Single Event Upsets). AI hardware for space must be “radiation-hardened,” which often means it is older, slower, and much more expensive than consumer tech on Earth. Running modern neural networks on 10-year-old equivalent processors requires extreme software optimization.

3. “AI removes the need for bandwidth”

Reality: While edge AI reduces the amount of raw data sent, it increases the need for sophisticated telemetry. Engineers need to know why the AI made a decision. If the AI deletes an image because it “thought” it was cloudy, engineers need verification to trust the system hasn’t started deleting good data.

Challenges and Risks

Implementing AI governance frameworks in space is fraught with technical and ethical challenges.

The Radiation Barrier

As mentioned, cosmic rays degrade electronics. To run advanced machine learning in space, engineers are developing “software-hardened” techniques where the software detects and corrects radiation-induced errors in the AI calculations, allowing the use of faster, commercial-grade chips.

The “Black Box” Trust Issue

Space missions cost billions. Engineers are risk-averse. They need to know exactly why a spacecraft fires a thruster. Deep Learning models are often “black boxes”—we know the input and output, but the internal logic is opaque. “Explainable AI” (XAI) is a critical field of research for space agencies. Before NASA hands over full control of a nuclear-powered rover to an algorithm, they need to be able to mathematically verify its decision-making boundaries.

Power Constraints

Spacecraft run on solar panels and batteries. Running heavy GPU computations drains power. AI models for space must be “quantized” and compressed to run on very low wattage (sometimes less than a standard lightbulb).

Who This Is For (And Who It Isn’t)

This guide is for:

- Space Industry Professionals: Engineers and analysts looking to understand the integration of autonomy in mission architecture.

- Tech Enthusiasts & Developers: Readers interested in edge computing, robotics, and how ML constraints differ in extreme environments.

- Students & Educators: Those researching the intersection of aerospace engineering and computer science.

This guide is not for:

- Sci-Fi Writers: Looking for speculative fiction about sentient starships (though real tech inspires it, this is about current capabilities).

- General Astrophotographers: Looking for tips on how to use AI to process their backyard telescope photos (this focuses on institutional mission hardware).

How We Evaluated: The Technology Readiness

To understand where these technologies stand, we look at Technology Readiness Levels (TRL), a scale from 1 (basic principles) to 9 (flight-proven).

1. Autonomous Navigation (TRL 9)

Proven on Mars (Perseverance) and asteroid missions (OSIRIS-REx). This is mature technology actively being refined for higher speeds and rougher terrain.

2. On-Board Image Filtering (TRL 7-8)

Demonstrated on missions like Φ-sat-1 and various commercial Earth observation satellites. Becoming a standard feature for new commercial constellations.

3. Autonomous Swarm Control (TRL 4-5)

Still largely experimental. While formation flying exists, true “hive mind” autonomy where satellites self-organize without pre-programmed slots is mostly in the research and university satellite phase.

4. Semantic Communication (TRL 3-4)

Using AI to reconstruct meaning from highly corrupted signals (beyond standard error correction) is largely in the lab phase, being tested for future deep-space internet protocols.

Conclusion

AI in space exploration is not just about smarter robots; it is about extending the reach of humanity. By outsourcing the second-by-second survival decisions to autonomous spacecraft, we free up human minds to focus on the science—the search for life, the understanding of cosmic origins, and the protection of our home planet.

As we move toward 2030, expect to see the definition of “spacecraft” change. They will no longer be remote-controlled drones, but independent explorers, capable of traversing the ice shells of Europa or the methane lakes of Titan entirely on their own, phoning home only when they have found something wonderful.

Next Steps: If you are a developer, look into “Edge Impulse” or “TensorFlow Lite” to understand how models are compressed for low-power devices. If you are a student, follow the updates from the NASA JPL AI group or the ESA Advanced Concepts Team to see these algorithms in action.

FAQs

What is the primary role of AI in space exploration?

The primary role is autonomy. AI allows spacecraft to operate independently of Earth, managing navigation, health monitoring, and data processing without waiting for commands that are delayed by the vast distances of space.

How does AI help with space debris?

AI helps by processing tracking data from radar and telescopes to identify debris objects and predict their orbits more accurately. Onboard AI in satellites can also automatically calculate and execute maneuvers to avoid collisions with this debris.

Can AI replace astronauts?

No, AI is designed to augment astronauts, not replace them. While robotic probes can go where humans cannot, AI in crewed missions (like CIMON) acts as an assistant, handling routine tasks, monitoring systems, and providing information so astronauts can focus on complex work.

Why is latency a problem for space missions?

Radio waves travel at the speed of light, but space is huge. A signal to Mars takes anywhere from 3 to 22 minutes to arrive. This means real-time “joysticking” of a rover is impossible; the rover must be smart enough to drive itself to avoid falling off a cliff before the operator even sees the cliff.

What is Edge AI in satellites?

Edge AI refers to processing data directly on the satellite (the “edge” of the network) rather than sending raw data to Earth. This saves bandwidth and allows for faster reaction times, such as detecting a forest fire and alerting ground crews immediately.

What computer languages are used for Space AI?

C++ and Python are common. C++ is favored for flight software due to its performance and direct hardware control. Python is often used for training models on the ground, which are then converted (transpiled) to C++ or specialized formats for the spacecraft’s onboard processor.

Is AI used in the search for extraterrestrial life?

Yes. Machine learning algorithms analyze vast datasets from radio telescopes (SETI) and optical telescopes (TESS/Kepler) to identify anomalous signals or planet transit patterns that stand out from cosmic background noise, which could indicate life or habitable worlds.

How do satellites avoid crashing into each other?

Satellites use orbit propagation algorithms to predict future positions. Modern mega-constellations like Starlink use autonomous onboard systems that receive position data from other satellites and automatically fire thrusters to dodge potential collisions without human intervention.

What is the Deep Space Network?

The Deep Space Network (DSN) is a collection of giant radio antennas on Earth (in California, Spain, and Australia) used to communicate with spacecraft beyond the Moon. AI helps schedule these antennas and optimize signal encoding to get the most data out of the limited connection time.

Are there risks to using AI in space?

Yes. The main risks are “black box” failures (where the AI makes a wrong decision and engineers cannot determine why) and hardware failure due to radiation. Space agencies use rigorous testing and “radiation-hardened” designs to mitigate these risks.

References

- NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “Artificial Intelligence at JPL.” JPL Science and Technology. https://www-robotics.jpl.nasa.gov/

- European Space Agency (ESA). “Artificial Intelligence in Space.” ESA Enabling & Support.

- NASA. “Mars 2020 Mission: Perseverance Rover AutoNav.” NASA Mars Exploration Program. https://mars.nasa.gov/mars2020/mission/technology/

- European Space Agency (ESA). “Phi-Sat-1: The First AI Chip in Space.” ESA Earth Observation.

- NASA. “Space Debris and Human Spacecraft.” NASA Orbital Debris Program Office. https://orbitaldebris.jsc.nasa.gov/

- Garrison, J. (2025). “Deep Learning for Spacecraft Guidance and Control.” Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. (AIAA). https://arc.aiaa.org/journal/jsr

- Starlink. “Autonomous Collision Avoidance System.” SpaceX Updates. https://www.spacex.com/updates/

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). “AI for Good: Space.” ITU Publications. https://aiforgood.itu.int/

- Airbus. “CIMON: The AI Assistant for Astronauts.” Airbus Space.

- The Planetary Society. “How We Communicate with Mars.” Planetary Society Guides.

- Nature Astronomy. (2024). “Machine learning for exoplanet detection.” Nature Portfolio. https://www.nature.com/nateastron/

- NASA Technology Transfer. “Visual SLAM for Autonomous Navigation.” NASA Spinoff. https://spinoff.nasa.gov/