The way we design the physical world is undergoing a fundamental shift. For centuries, design was a direct act of human will: an engineer or architect would sketch a concept, refine the geometry, and validate it against physics. Today, artificial intelligence has turned this process on its head. Instead of drawing the shape, designers now define the goals and constraints, and the computer draws the shape for them—thousands of times over.

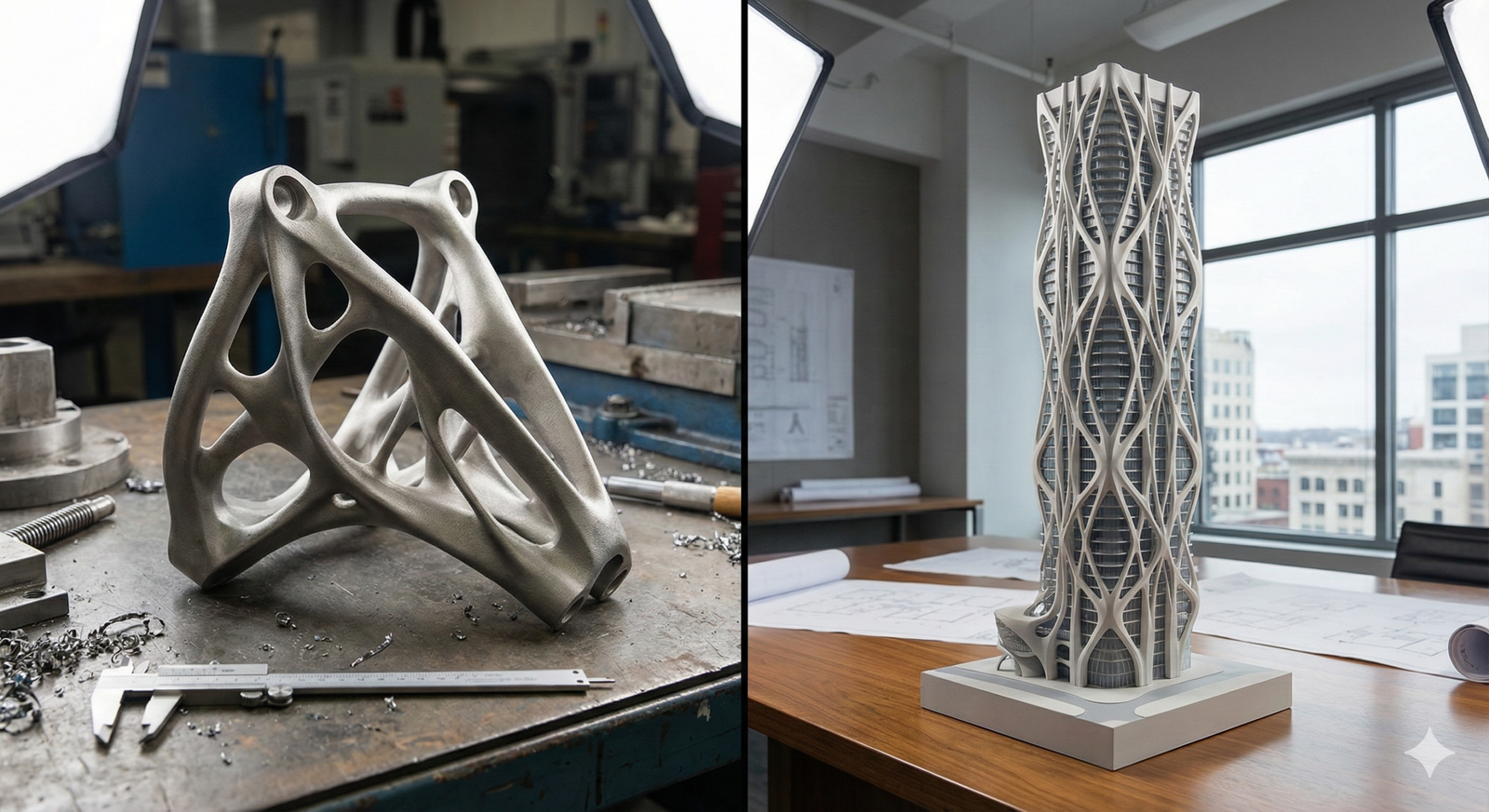

This is generative design. It is not merely a faster way to draw; it is a collaborative partnership between human creativity and machine intelligence. By leveraging cloud computing and evolutionary algorithms, generative design allows software to explore the entire solution space of a design problem, returning options that no human mind could conceive on its own. From lightweight aircraft components that look like organic bones to office floor plans that maximize collaboration, generative design is rewriting the rules of manufacturing and construction.

This comprehensive guide explores the mechanisms, applications, benefits, and future of generative design in product development and architecture.

Key Takeaways

- Goal-Driven Process: Unlike traditional CAD (Computer-Aided Design), generative design starts with constraints (loads, materials, manufacturing methods) rather than geometry.

- Radical Efficiency: It frequently results in parts that are lighter, stronger, and use less material than human-designed counterparts.

- Biomimetic Aesthetics: The resulting forms often resemble organic structures (bones, roots, webs) because the algorithms mimic nature’s evolutionary approach to stress distribution.

- Sustainability Engine: By optimizing material usage and enabling lighter vehicles/buildings, generative design significantly reduces carbon footprints.

- Manufacturing Agnostic: Modern tools can generate options specifically optimized for 3D printing (additive), CNC machining (subtractive), or casting.

Who This Is For (And Who It Isn’t)

This guide is for:

- Product Designers and Engineers looking to overcome engineering blocks and optimize part performance.

- Architects and Civil Engineers interested in structural optimization and space planning automation.

- Manufacturing Executives seeking to reduce material costs and lead times.

- Students and Enthusiasts wanting to understand the intersection of AI, physics, and creation.

This guide is NOT for:

- Generative Art Enthusiasts: While related in name, this article focuses on engineering and functional design, not “Generative AI” for creating 2D art (like Midjourney or DALL-E) unless it pertains to physical form finding.

- Those seeking a specific software manual: We discuss workflows conceptually, but this is not a click-by-click tutorial for a specific software package like Fusion 360 or Grasshopper.

Defining Generative Design: Beyond the Buzzword

To understand generative design, we must first distinguish it from the technologies often confused with it. It is frequently conflated with topology optimization or parametric design, but while related, they occupy different rungs on the evolutionary ladder of design software.

1. Parametric Design vs. Generative Design

Parametric design allows a user to define relationships between elements. For example, “if the wall gets longer, add more windows.” The computer updates the model based on these rules. However, the computer is not “thinking” or exploring new options; it is simply executing a predefined script. The human is still the pilot; the computer is the steering mechanism.

2. Topology Optimization vs. Generative Design

Topology optimization takes an existing human-designed block and whittles away material that isn’t bearing any load. It refines a known solution. Generative design, by contrast, explores the unknown. It builds from the ground up (or rather, from the connection points out) to find a valid geometry. It doesn’t just make a part lighter; it might invent a completely new shape that combines three parts into one.

The Generative Definition

Generative design is an iterative design process that involves a program that will generate a certain number of outputs that meet certain constraints, and a designer that will fine-tune the feasible region by changing minimal and maximal values of an interval in which a variable of the program meets the set of constraints, in order to reduce or augment the number of outputs to choose from.

In plain English: You tell the AI what you want to achieve (e.g., “hold 500kg, weigh less than 2kg, cost under $50”), and the AI grows the part for you.

How It Works: The Evolutionary Algorithm

The “magic” behind generative design is rooted in biomimicry—imitating the biological strategies found in nature. Nature is the ultimate generative designer. Over millions of years, evolution “iterates” on the design of a bone or a tree branch. If a variation is too heavy or too weak, it fails (goes extinct). If it is efficient, it survives.

Generative design software accelerates this evolutionary timeline from millions of years to a few hours using cloud computing.

The 4-Step Workflow

- Define (The Setup): The engineer does not draw the part. Instead, they define the “preserve geometry” (connection points, bolt holes, interfaces that must exist) and “obstacle geometry” (areas where material cannot go, such as where a tool needs access or a wire must pass).

- Constraints & Objectives: The user inputs the physics:

- Loads: Forces, pressures, and moments the part must withstand.

- Materials: Titanium, aluminum, plastic, concrete, etc.

- Manufacturing: Is this being 3D printed? Milled? Cast? (This is crucial, as the AI will avoid creating shapes that cannot be manufactured).

- Generate (The AI Loop): The software uses algorithms (often finite element analysis combined with search algorithms) to generate hundreds or thousands of high-fidelity design options. It creates a design, simulates a stress test, learns where it failed or where it has excess material, creates a variation, and repeats.

- Explore & Select: The user receives a matrix of solutions. They can filter these results using scatter plots—for example, plotting “Safety Factor” against “Mass.” The designer explores the trade-offs and selects the option that best fits the project goals.

Applications in Product Design and Manufacturing

The impact of generative design on physical products is profound. It is moving manufacturing away from the geometric simplicity of the industrial revolution (straight lines, flat surfaces) toward the organic complexity of the digital age.

1. Automotive Lightweighting

In the automotive industry, mass is the enemy of efficiency. For internal combustion vehicles, more weight equals higher fuel consumption. For electric vehicles (EVs), weight directly reduces range.

Generative design is used to redesign heavy components like seat brackets, suspension control arms, and seatbelt anchors. A classic example involves replacing a multi-part welded steel assembly with a single-piece generative part. The AI typically produces a lattice-like structure that removes material from low-stress areas and reinforces high-stress paths.

- Result: Parts that are 30–50% lighter but maintain or exceed the structural integrity of the original.

- Part Consolidation: Because generative design thrives on complexity (which comes “free” with additive manufacturing), engineers can combine assemblies of 10 or 20 parts into a single printed unit, reducing inventory, assembly time, and failure points.

2. Aerospace and Space Exploration

In aerospace, the cost of launching a kilogram of payload into space is astronomical. Consequently, the value of weight reduction is higher here than in any other industry. NASA and commercial space companies use generative design for interplanetary landers and satellite components.

- Complex Constraints: Spacecraft parts face extreme thermal fluctuations and vibrational loads during launch. Generative algorithms can optimize for these multimodal physics scenarios simultaneously, creating “bionic” structures that human engineers would struggle to calculate manually.

3. Consumer Goods and Sports Equipment

From shoe soles to bicycle frames, consumer goods are leveraging generative design for performance and customization.

- Performance Footwear: Shoe companies collect data on a runner’s stride and pressure distribution. Generative algorithms use this data to create a custom lattice midsole that provides varying stiffness and support exactly where that specific runner needs it.

- Sports Equipment: Bicycle stems and cranks are being redesigned to handle the specific torques of professional cycling while shaving off grams that matter in competitive racing.

4. Medical Implants

Human bone is not solid; it is a porous matrix that balances strength with weight. Traditional titanium implants are often solid, which can lead to “stress shielding”—where the bone creates less density because the implant takes too much load.

- The Solution: Generative design creates implants with porous, bone-like micro-structures (lattices). This matches the stiffness of the patient’s real bone and encourages osseointegration (bone growing into the implant), leading to faster recovery and longer-lasting implants.

Applications in Architecture and Construction (AEC)

While product design focuses on the object, architecture focuses on the system. Generative design in the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry operates at two scales: the macro (building layout/urban planning) and the micro (structural connections).

1. Space Planning and Urban Design

Designing a floor plan for a large office or a hospital is a complex logic puzzle. Architects must balance occupancy capacity, walking distances, daylight access, fire egress, and department adjacencies.

- Generative Solvers: An architect defines the goals: “Fit 500 desks, ensure every desk is within 20 feet of a window, and minimize the distance between the breakroom and the engineering team.”

- The Output: The AI generates thousands of floor plan iterations. The architect can then choose the one that creates the best “vibe” or workflow, knowing the metrics are already optimized. This was famously demonstrated in the redesign of Autodesk’s MaRS office in Toronto, where AI helped navigate competing stakeholder goals.

2. Structural Optimization

Skyscrapers and large-span roofs require massive amounts of steel and concrete. Generative design creates structural trusses and beams that place material only where the load paths dictate.

- Material Reduction: By optimizing the internal structure of concrete slabs or steel nodes, engineers can reduce raw material usage by significant margins. In an industry responsible for a large percentage of global CO2 emissions, this efficiency is critical for sustainability.

3. Site Optimization

Before a building is designed, the site must be analyzed. Generative design can analyze a plot of land to determine the optimal orientation and massing of a building to maximize solar gain (for heating efficiency) or views, while minimizing wind tunnel effects or noise pollution.

The Role of Manufacturing Methods

Generative design is intrinsically linked to how the object will be made. The geometric complexity of the output often dictates the manufacturing process.

Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing)

Generative design and 3D printing are often viewed as “best friends.” The organic, undercut-heavy, hollow shapes produced by algorithms are often impossible to machine or cast using traditional molds. 3D printing has no penalty for complexity—printing a solid cube costs roughly the same time and effort as printing a complex lattice cube of the same volume. This synergy allows the full creative potential of generative design to be realized.

Constraints for Subtractive Manufacturing

However, generative design is not exclusive to 3D printing. Modern algorithms now include “manufacturing constraints.”

- 3-Axis/5-Axis Milling: You can tell the AI, “I only have a 3-axis CNC machine.” The AI will then generate shapes that avoid undercuts and ensure the tool can access all surfaces.

- Casting: You can constrain the AI to ensure the part has a “draft angle” so it can be pulled out of a mold.

This flexibility is what makes the technology scalable today, rather than just a futuristic concept for high-end prototypes.

Benefits of Generative Design

Why are companies investing in this technology? The return on investment comes from three main areas:

1. Innovation and Creativity

Designers often fall into “cognitive ruts,” reusing similar geometries because they know they work. Generative design removes this bias. It provides “alien” solutions that no human would intuitively draw, often unlocking performance breakthroughs that were previously hidden.

2. Light-weighting and Material Efficiency

Reducing mass is a direct cost saver in aerospace and automotive fuel. Furthermore, using less material reduces the upfront cost of goods sold. Even a 10% reduction in material across a production run of a million units results in massive savings.

3. Speed to Market

Traditional design involves a linear loop: Design -> Simulate -> Fail -> Redesign. Generative design essentially does the simulation during the design creation. The result is a validated part much earlier in the cycle, reducing the time spent on trial-and-error testing.

4. Part Consolidation

As mentioned, merging multiple parts into one reduces assembly labor, creates a more robust supply chain (fewer SKUs to manage), and eliminates failure points like loosening bolts or leaking welds.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite its promise, generative design is not a “make it perfect” button. It faces several hurdles that prevent universal adoption.

1. The “Black Box” Problem

Engineers are trained to understand why a design works. When an AI generates a complex organic web, it can be difficult to verify its safety without extensive secondary testing. The lack of clear geometric logic (like simple beams and columns) can make certification authorities (like the FAA or building code officials) hesitant to approve these designs without rigorous, expensive physical testing.

2. Computational Cost

Running evolutionary algorithms requires significant processing power. While cloud computing makes this accessible, it can still be expensive and time-consuming for very complex, multi-physics problems.

3. Manufacturing Reality

While software can constrain for manufacturing, it isn’t perfect. It can still generate geometry that is technically printable but creates issues with thermal warping, support removal, or surface finish quality. The bridge between the “digital twin” and the physical part still requires human oversight.

4. The Learning Curve

Transitioning from explicit modeling (drawing lines) to implicit modeling (defining constraints) requires a different mindset. Designers need to learn how to “speak physics” to the software. If the constraints are set up poorly (e.g., forgetting a specific force vector), the AI will generate a perfect solution to the wrong problem, leading to catastrophic failure.

The Future: Beyond Geometry

As generative design matures, it is moving beyond static geometry into new frontiers.

1. Multi-Physics and Multi-Material

Future algorithms will be better at optimizing for multiple contradictory physical phenomena simultaneously—such as optimizing for structural integrity, fluid dynamics (cooling), and electromagnetism all at once. We will also see designs that vary material composition at the voxel level (e.g., a part that transitions from rigid titanium to flexible rubber).

2. Generative Urbanism

We will see city-scale generative models that optimize traffic flow, energy consumption, and social interaction, helping urban planners design resilient cities for a changing climate.

3. 4D Printing and Active Structures

Combining generative design with “4D printing” (materials that change shape over time or in response to stimuli) could lead to adaptive architectures—buildings that “grow” or shape-shift to optimize for changing weather conditions.

Conclusion

Generative design represents a transition from the era of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) to Computer-Aided Engineering (CAE) and Creation. It frees the designer from the tedium of drawing and geometry manipulation, elevating them to the role of conductor.

For the product designer, it offers a path to lighter, stronger, and more sustainable goods. For the architect, it offers a way to navigate the immense complexity of modern habitation. While it does not replace the human need for judgment, aesthetics, and empathy, it provides a toolset of unprecedented power.

As we look toward a future constrained by limited resources and the need for sustainability, the ability to do more with less—which is the core promise of generative design—is not just a competitive advantage; it is a necessity.

FAQs

Q: Is generative design the same as AI art generators? A: No. AI art generators (like Midjourney) use neural networks trained on images to create visual media based on text prompts. Generative design uses physics algorithms and engineering constraints to create functional 3D geometry that must withstand real-world forces.

Q: Does generative design replace engineers? A: No. It changes the engineer’s role. Instead of focusing on geometry creation, the engineer focuses on problem definition, constraint setting, and result validation. The “garbage in, garbage out” rule applies strictly here; the AI needs a skilled engineer to define the problem correctly.

Q: Can generative design be used with standard CNC machines? A: Yes. Modern generative design software (like Autodesk Fusion 360) allows users to set “manufacturing constraints” for 2.5-axis, 3-axis, and 5-axis milling, ensuring the output can be machined using traditional subtractive methods.

Q: Is generative design expensive? A: The software can be costly, and the computational credits required for cloud processing can add up. However, for high-value parts (aerospace, automotive, high-performance sports), the savings in material and the performance gains usually justify the investment.

Q: Why do generative designs look organic? A: They look organic because the algorithms often use principles similar to biological growth (like bone remodeling). Nature puts material only where stress flows; generative algorithms do the same, resulting in curved, lattice-like structures that resemble trees, bones, or webs.

References

- Autodesk. (2023). What is Generative Design? Autodesk Research.

- NASA. (2022). Evolved Structures: Generative Design for Spaceflight. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- Oh, S., et al. (2019). Deep Generative Design: Integration of Topology Optimization and Generative Models. Journal of Mechanical Design.

- Shea, K., et al. (2005). Towards a grammatical approach to structural design. Architectural Engineering and Design Management.

- General Motors. (2018). GM and Autodesk define the future of making things. General Motors Press Release.

- Airbus. (2019). The Bionic Partition: A case study in generative design. Airbus Innovation.