The global demographic landscape is shifting dramatically. As the population ages, the demand for elder care is outpacing the supply of human caregivers, creating a crisis that researchers and healthcare providers are scrambling to solve. Into this gap steps a promising, though sometimes controversial, solution: social robots. These represent a unique intersection of artificial intelligence, psychology, and healthcare, designed not to physically lift patients, but to lift their spirits, monitor their health, and provide cognitive engagement.

Social robots in elder care are no longer the stuff of science fiction. From robotic seals providing comfort to dementia patients in Japan to proactive desktop assistants keeping seniors company in the United States, these devices are being integrated into therapy and daily living at an increasing rate. However, the adoption of this technology brings with it complex questions regarding efficacy, ethics, and the very nature of care.

Disclaimer: This article explores the technology and applications of social robots in elder care and therapy. It is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Decisions regarding the care of elderly individuals or those with medical conditions should always be made in consultation with qualified healthcare professionals.

Scope of This Guide

In this guide, “social robots” refers to autonomous or semi-autonomous robots designed primarily to interact with humans on a social-emotional level. This includes:

- Therapeutic robotic pets (e.g., Paro, Joy for All).

- Social assistive robots (e.g., ElliQ, Pepper).

- Telepresence robots with social features (e.g., Temi).

This guide does not focus heavily on physical assistive robotics (like exoskeletons for walking or robotic arms for feeding), except where their functions overlap with social interaction.

Key Takeaways

- Addressing Loneliness: Social robots are proven tools for mitigating loneliness and social isolation among the elderly, acting as a bridge to the outside world.

- Dementia Therapy: Bio-feedback robots like Paro have shown significant success in non-pharmacological therapy for reducing agitation in dementia patients.

- Proactive Engagement: Modern AI agents like ElliQ do not wait for commands; they initiate conversation, promoting cognitive health and medication adherence.

- Ethical Balance: The use of robots requires navigating the “uncanny valley” and addressing concerns about deception, infantilization, and data privacy.

- Augmentation, Not Replacement: Experts agree that social robots are most effective when used to augment human care, not to replace the human touch entirely.

1. What Are Social Robots? Defining the Technology

To understand the impact of social robots in elder care, we must first define what makes a robot “social.” Unlike industrial robots designed to perform repetitive physical tasks with precision (like welding a car), social robots are designed to interact with people in a way that follows social behaviors and rules.

The Core Components

A social robot typically integrates several advanced technologies:

- Perception Systems: Cameras and microphones allow the robot to detect faces, recognize emotions (via facial expression analysis), and process speech.

- Natural Language Processing (NLP): This allows the robot to understand spoken language and respond appropriately. With the advent of Large Language Models (LLMs), these conversations are becoming increasingly fluid and less scripted.

- Social Intelligence: The software is programmed to mimic social cues, such as making eye contact, nodding, or using intonation that conveys empathy.

- Expressive Mechanics: Many social robots have physical features—eyes, lights, or moving parts—that allow them to display “body language.”

Categories of Social Robots in Care

We can generally categorize these devices into three functional groups:

- Therapeutic Companions: These are often zoomorphic (animal-shaped). Their primary goal is to elicit an emotional response, provide tactile comfort, and reduce stress. They are widely used in memory care units.

- Service & Assistance Robots: These are often humanoid or desktop-based. They function as personal assistants, managing schedules, offering reminders, and facilitating video calls, but with a personality that encourages engagement.

- Socially Assistive Robots (SARs): These robots focus on rehabilitation or specific health goals, such as leading an exercise class for seniors or coaching a patient through cognitive therapy exercises.

2. The Growing Need for Robotics in Senior Care

The integration of robotics into geriatrics is driven by necessity as much as innovation. Several converging trends are forcing a re-evaluation of how we deliver care to the elderly.

The Demographics of Aging

Globally, the number of people aged 60 years and older is growing faster than any other age group. According to the World Health Organization, the proportion of the world’s population over 60 will nearly double from 12% to 22% between 2015 and 2050. In countries like Japan, Italy, and Germany, the “super-aged” society is already a reality.

The Caregiver Shortage

As the population ages, the workforce shrinks. There is a massive global shortage of nurses, geriatricians, and home health aides. This shortage leads to:

- Caregiver Burnout: Professional caregivers are overworked, leading to high turnover rates.

- Family Strain: Adult children often shoulder the burden of care, balancing it with their own careers and children (the “sandwich generation”).

- Decreased Quality of Care: With fewer staff members per resident in care homes, social interaction is often the first thing to suffer. Staff may have time to administer medicine and food, but not to sit and chat for 30 minutes.

The Epidemic of Loneliness

Loneliness is a critical health crisis among the elderly. Studies have consistently linked social isolation to higher risks of:

- High blood pressure and heart disease.

- Obesity and a weakened immune system.

- Depression and anxiety.

- Cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease.

Social robots act as a dedicated presence that is always available, never gets tired, and never gets impatient, helping to fill the “social void” when human interaction is unavailable.

3. How Social Robots Support Mental Health and Therapy

The application of social robots in therapy—particularly for those with cognitive impairments—is one of the most well-researched areas in this field.

Non-Pharmacological Intervention for Dementia

Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease often present behavioral symptoms such as agitation, aggression, wandering, and apathy. Traditionally, these are managed with antipsychotic medications, which can have severe side effects (sedation, increased risk of falls).

Social robots offer a non-pharmacological alternative.

- Sensory Stimulation: Robots with fur or tactile sensors provide sensory feedback that grounds patients.

- Reminiscence Therapy: Robots can be programmed to play music from the user’s youth or display photos, triggering memories and conversation.

- Reducing Agitation: The act of nurturing a robotic pet can calm a distressed patient, tapping into long-held caregiving instincts that remain even when other cognitive faculties decline.

Cognitive Stimulation and Maintenance

For seniors without dementia, or those with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), “use it or lose it” is the guiding principle for brain health. Social robots can:

- Host Trivia and Games: Interactive games that require memory and logic help maintain neural pathways.

- Encourage Storytelling: By asking open-ended questions about the user’s day or past, the robot forces the user to articulate thoughts, which is vital for cognitive maintenance.

Managing Anxiety and Depression

Depression in the elderly is often under-diagnosed. Robots can serve as a non-judgmental entity to which a senior can express feelings. While a robot cannot “cure” depression, the consistent presence and the routine of interacting with the device can provide a stabilizing daily structure, which is beneficial for mental health.

4. Leading Social Robots Currently in Use

To understand what this looks like in practice, we must examine the specific hardware currently deployed in homes and facilities.

Paro: The Therapeutic Seal

Developed by AIST in Japan, Paro is perhaps the most famous social robot in elder care. It looks like a baby harp seal.

- Why a seal? Most people have no preconceived notion of how a seal should behave, unlike a dog or cat, allowing users to accept Paro without judging its realism.

- Function: It is covered in antimicrobial fur and packed with tactile sensors. It responds to touch by moving its tail and opening its eyes. It creates an emotional bond with the patient.

- Use Case: Highly effective in reducing stress for patients with advanced dementia who may no longer be able to communicate verbally.

ElliQ: The Proactive Companion

Created by Intuition Robotics, ElliQ is designed for “aging in place”—helping seniors live independently at home. It is a tabletop device with a moving “head” (light and screen).

- Mechanism: Unlike smart speakers (Alexa/Siri) that wait for a “wake word,” ElliQ is proactive. It might say, “Good morning, it looks sunny today, have you taken your walk?” or “You haven’t played a trivia game in a while, want to try?”

- Use Case: Combating loneliness and facilitating health management for independent seniors.

Joy for All (Ageless Innovation)

These are animatronic cats and dogs that are significantly more affordable than Paro.

- Function: They purr, bark, and roll over in response to touch.

- Use Case: Providing the comfort of a pet without the responsibilities (feeding, vet bills, allergies) or risks (tripping hazards, scratches) associated with live animals.

Pepper and Nao (SoftBank Robotics)

While Pepper (the humanoid robot) has seen reduced production, it remains a staple in research and some luxury care facilities.

- Function: Pepper can lead exercise classes, tell jokes, and guide residents through facility corridors. Its humanoid form allows for gesturing, which helps in group settings.

5. Benefits of Integrating Robots into Care Plans

When implemented correctly, social robots offer distinct advantages that go beyond simple novelty.

1. Consistent, Patience-Unlimited Interaction

Human caregivers, no matter how dedicated, have bad days. They get tired, frustrated, or busy. A robot never judges a senior for repeating the same story ten times in an hour. This limitless patience is crucial for preserving the dignity of seniors who are aware of their declining faculties and fear being a burden.

2. The “Social Lubricant” Effect

Research has shown that the presence of a robot in a common area of a care home increases interaction between residents. The robot becomes a conversation piece. Residents who might sit silently otherwise will talk to each other about the robot (“Look what it did,” “Is it looking at you?”), thereby fostering human-to-human connection.

3. Monitoring and Safety

Social robots can double as safety devices.

- Anomaly Detection: If a senior usually says “Good morning” to their robot at 8:00 AM but hasn’t appeared by 9:00 AM, the robot can alert a family member.

- Hydration and Medication: Robots can track adherence to medication schedules in a friendly, non-nagging way.

4. Independence and Dignity

For many seniors, asking a human for help with small things (like “what day is it?”) feels like admitting defeat. Asking a robot is neutral. It allows seniors to maintain a sense of control over their environment and information without feeling dependent on another person.

6. Challenges and Limitations

Despite the benefits, the widespread adoption of social robots faces significant hurdles.

Technical Limitations (The “Gap” in AI)

While Generative AI is improving rapidly, many robots still struggle with:

- Speech Recognition: Seniors often have softer voices or speech patterns affected by strokes or dental issues. Standard voice recognition models often fail in these scenarios.

- Contextual Understanding: A robot might not understand the difference between a user crying because they are sad versus crying because they are laughing. Misinterpreting emotional cues can lead to inappropriate responses that break the trust.

The “Uncanny Valley”

This psychological concept suggests that as a robot appears more human, our empathy towards it increases, until it gets too close to human-like but not quite perfect. At that point, it becomes repulsive or creepy (zombie-like).

- Design Choice: This is why robots like Paro (seal) or ElliQ (lamp-like) often succeed better than hyper-realistic androids. They avoid the uncanny valley by not trying to be human.

Cost and Accessibility

Robots like Paro can cost thousands of dollars (often around $6,000 USD). While insurance models are exploring coverage for therapeutic devices, the cost remains a barrier for many families and underfunded care facilities.

Hardware Maintenance

In a care facility, devices get dropped, spilled on, or simply wear out. Maintaining a fleet of robots requires IT support that many nursing homes do not possess.

7. Ethical Implications of AI-Generated Faces and Personalities

The deployment of social robots raises profound ethical questions that philosophers and bioethicists debate heavily.

The Deception Dilemma

Is it ethical to allow an elderly person with dementia to believe a robot is a living thing?

- The Argument Against: It acts as a deception, creating a false reality and potentially violating the dignity of the patient by treating them like a child (infantilization).

- The Argument For: If the interaction brings the patient joy and reduces their suffering (anxiety/fear), the “lie” is benevolent. This is often compared to “validation therapy,” where caregivers do not correct a dementia patient’s delusions but step into their reality to provide comfort.

Privacy and Data Security

Social robots collect vast amounts of intimate data. They listen to conversations, map the home layout, and track daily routines.

- Consent: Can a patient with cognitive decline validly consent to being monitored by an AI?

- Data Ownership: Who owns the data on the senior’s mood fluctuations? The family? The insurance company? The robot manufacturer? Strict adherence to regulations like HIPAA (in the US) and GDPR (in Europe) is essential.

Replacement vs. Augmentation

The greatest fear is that robots will be used to cut costs and replace human staff, leaving seniors in a “cold,” automated environment.

- The Reality: The consensus in the industry is that robots should handle the repetitive/monitoring tasks to free up human caregivers to do what humans do best: provide empathy, touch, and complex emotional support.

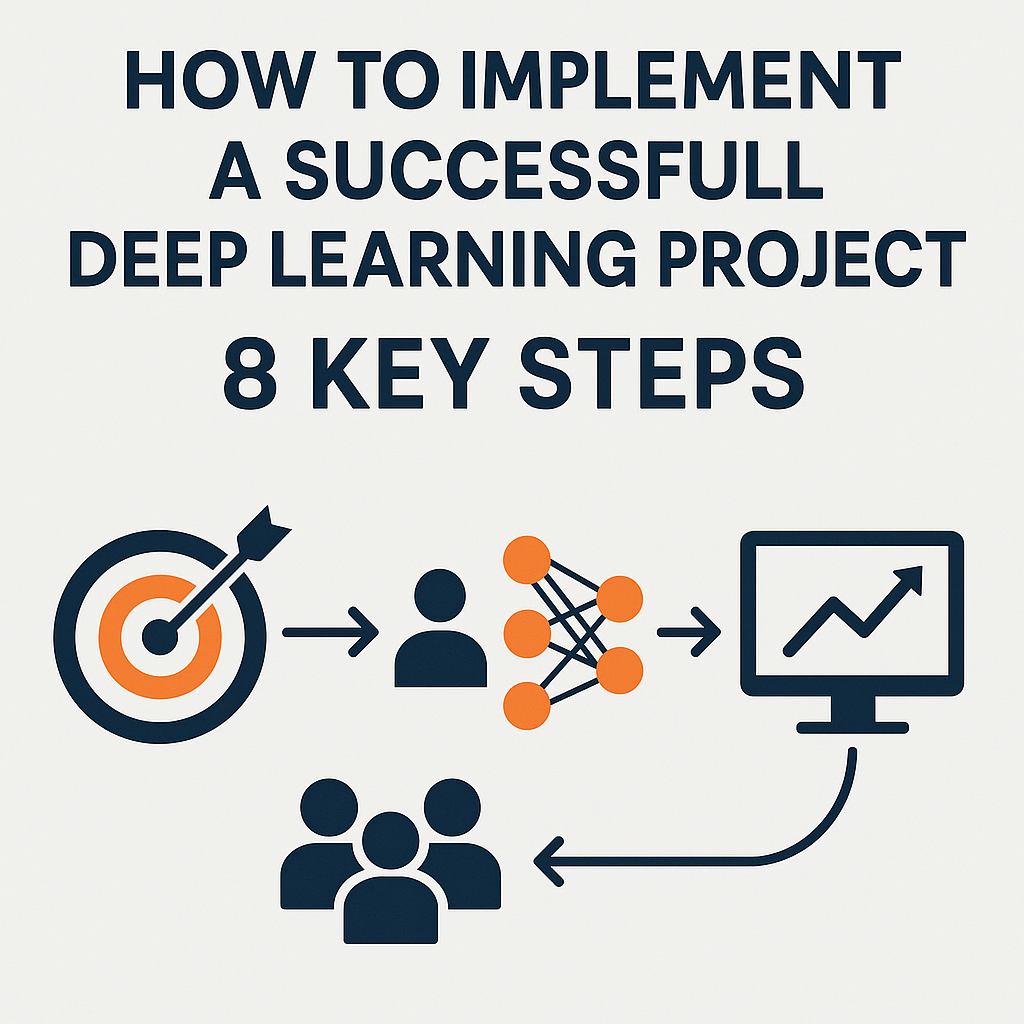

8. Implementing Social Robots: A Guide for Families and Facilities

If you are considering introducing a social robot to an elderly loved one or a care facility, a strategic approach is necessary for success.

Step 1: Assess the Need

Identify the specific gap you are trying to fill.

- Is it loneliness? A chatty robot like ElliQ might be best.

- Is it anxiety/dementia? A tactile pet like Paro or Joy for All is superior.

- Is it safety? A telepresence robot that allows family to “drop in” might be the priority.

Step 2: The Introduction Phase

Never simply leave the robot in the room. The introduction must be facilitated.

- Demonstrate: Show the senior how to touch or speak to it.

- Frame the Relationship: Introduce the robot as a “helper” or a “friend,” not a toy.

- Trial Period: Allow for a rejection period. Not every senior likes robots; some may feel patronized or frightened.

Step 3: Ongoing Support

Ensure there is someone (a tech-savvy family member or staff member) responsible for:

- Charging the device.

- Updating the software.

- Checking the logs/dashboard for any alerts regarding the senior’s health.

9. The Future of AI and Robotics in Geriatrics

As of 2025 and moving into 2026, the landscape of social robotics is evolving through the integration of Generative AI.

Generative AI Integration

Older robots relied on decision trees (If A, say B). New robots integrated with Large Language Models (LLMs) can:

- Generate Dynamic Stories: Create bedtime stories or reminiscence narratives on the fly based on the senior’s past.

- Detect Cognitive Drift: By analyzing language patterns over months, AI agents may be able to detect subtle signs of worsening Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s (via speech changes) long before a human observer would notice.

Ambient Assisted Living (AAL)

Social robots will cease to be standalone devices and will become the interface for the entire smart home. The robot will communicate with smart fridges (nutrition tracking), smart beds (sleep tracking), and fall detection sensors, acting as the central hub of the senior’s health ecosystem.

Emotional Alignment

Future robots will utilize “Affective Computing” to better read micro-expressions. If a senior winces in pain while standing up, the robot will detect the pain expression and ask, “Are you hurting?” prompting a log entry for the doctor.

10. Common Mistakes When Adopting Care Robots

To maximize value, avoid these common pitfalls:

Mistake 1: Overestimating Capability

Families often expect a “Rosie the Robot” (from The Jetsons) that can cook and clean. Social robots are currently limited to interaction and monitoring. Setting realistic expectations prevents disappointment.

Mistake 2: Ignoring User Preference

Some seniors prefer a machine-like look (to keep the distinction clear), while others want a pet-like look. Failing to match the robot’s form factor to the user’s personality can lead to immediate abandonment of the device.

Mistake 3: “Set and Forget”

A social robot requires human oversight. If the robot disconnects from Wi-Fi or acts glitchy, it becomes a paperweight. Regular technical check-ins are mandatory.

Conclusion

Social robots represent a profound shift in how we approach elder care. They are not a panacea for the structural issues of aging societies, nor are they a replacement for the warmth of a human hand. However, as therapeutic tools, they offer immense value. They can soothe the agitated mind of a dementia patient, break the silence of a lonely afternoon, and provide a safety net for those aging in place.

As technology advances, the line between assistive device and companion will continue to blur. The challenge for society is not just to build better robots, but to build better care ecosystems where these robots are used ethically to enhance, rather than diminish, human dignity. For families and care providers, embracing this technology today means opening a door to better engagement, safety, and emotional well-being for the seniors of tomorrow.

FAQs regarding Social Robots in Elder Care

Q1: Can social robots really help with dementia? Yes. Clinical studies suggest that interacting with therapeutic robots like Paro can significantly reduce stress hormones (cortisol) and improve mood in patients with mild to severe dementia. They are effectively used to manage agitation and aggression without medication.

Q2: Are social robots covered by insurance or Medicare? As of early 2026, coverage is inconsistent. Some private insurance plans and specific Medicaid waivers in certain US states may cover assistive technology if deemed medically necessary, but widespread Medicare coverage for social robots specifically is not yet standard. It is best to check with specific providers.

Q3: Will the robot spy on my elderly parent? Privacy is a valid concern. Reputable manufacturers comply with data protection laws (HIPAA/GDPR). Most allow you to turn off cameras or delete data. However, they do collect data to function. It is crucial to read the privacy policy of the specific device before purchase.

Q4: How do I know if my parent will accept a robot? Acceptance varies. Previous exposure to technology helps, but is not required. Pet lovers often respond well to robotic pets. The best approach is a trial run. Some companies offer rental periods or return windows to see if the senior bonds with the device.

Q5: What is the difference between a service robot and a social robot? A service robot performs physical tasks (vacuuming floors, fetching water, lifting patients). A social robot focuses on interaction, conversation, emotional support, and cognitive engagement. Some future robots aim to combine both, but currently, they are mostly distinct categories.

Q6: Can these robots call 911 in an emergency? Some social robots generally do not call 911 directly to avoid false alarms. Instead, they act as emergency alert systems that contact pre-designated family members or a monitoring center, who can then dispatch emergency services if needed.

Q7: Do these robots require Wi-Fi to work? Most modern social robots (like ElliQ) require a stable Wi-Fi connection to process language and access updates. However, some therapeutic pets (like Joy for All) act as standalone mechanical devices and do not require an internet connection to provide comfort.

Q8: Are robotic pets better than real pets for seniors? For seniors who cannot physically care for a live animal (walking, feeding, cleaning litter boxes) or live in facilities that ban pets, robotic pets are a superior alternative. They offer the comfort of companionship without the physical demands or hygiene risks of a live animal.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2022). Ageing and health. Retrieved from WHO.int.

- Broadbent, E., et al. (2018). Robots in Health and Social Care: A Complementary Technology to Home Care and Telehealthcare?. Journal of Medical Internet Research.

- Wada, K., & Shibata, T. (2007). Living with Seal Robots—Its Sociopsychological and Physiological Influences on the Elderly at a Care House. IEEE Transactions on Robotics.

- Pu, L., et al. (2019). The Effectiveness of Social Robots for Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. The Gerontologist.

- Vanderschantz, N., et al. (2020). Ethical Considerations for the Design and Use of Social Robots in Elder Care. Ethics and Information Technology.

- Intuition Robotics. (2024). ElliQ: The Sidekick for Happier Aging. Official Documentation.

- Paro Robots U.S. (n.d.). Paro Therapeutic Robot. Official Product Documentation.

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2019). The risks of social isolation. Monitor on Psychology.

- Sharkey, A., & Sharkey, N. (2012). Granny and the robots: ethical issues in robot care for the elderly. Ethics and Information Technology.

- National Institute on Aging (NIA). (2023). Aging in Place: Growing Older at Home. NIA.nih.gov.