The relationship between AI and the arts has shifted rapidly from experimental novelty to a fundamental component of the modern creative workflow. For many observers, the narrative has been binary: either machines are replacing human creativity, or they are mere toys. However, the reality on the ground—in studios, writers’ rooms, and music production suites—is far more nuanced. We have entered the era of co-creation, where the algorithm acts not as a replacement for the artist, but as a collaborator, a provocateur, and a force multiplier.

This guide explores the practical reality of human-AI collaboration. It moves beyond the hype of “one-click masterpieces” to examine how professional artists are integrating artificial intelligence into their creative processes to break creative blocks, iterate faster, and explore aesthetics that were previously impossible to achieve.

Key Takeaways

- Co-creation vs. Generation: True co-creation involves an iterative loop between human intent and machine output, rather than passive consumption of AI-generated content.

- Tool Agnosticism: The most effective artists treat AI as another tool in the box, similar to a camera or a synthesizer, rather than an “easy button.”

- Ethical Complexity: Navigating the legal and ethical landscape—specifically regarding copyright and training data—is now a critical skill for the modern creative.

- Workflow Evolution: The “Sandwich Method” (Human start → AI iteration → Human finish) is becoming the standard model for professional quality control.

- Domain Expansion: While visual art grabs headlines, significant co-creation strides are occurring in music composition, literary plotting, and architectural design.

Scope of This Guide

In this guide, “co-creation” refers to workflows where human input and oversight remain central to the artistic output, using AI to augment capabilities rather than replace the creator. We will cover visual arts, music, and writing. We will not cover fully autonomous AI agents that generate content without human direction, nor will we provide legal advice regarding specific copyright filings.

Defining Human-AI Co-Creation in the Creative Economy

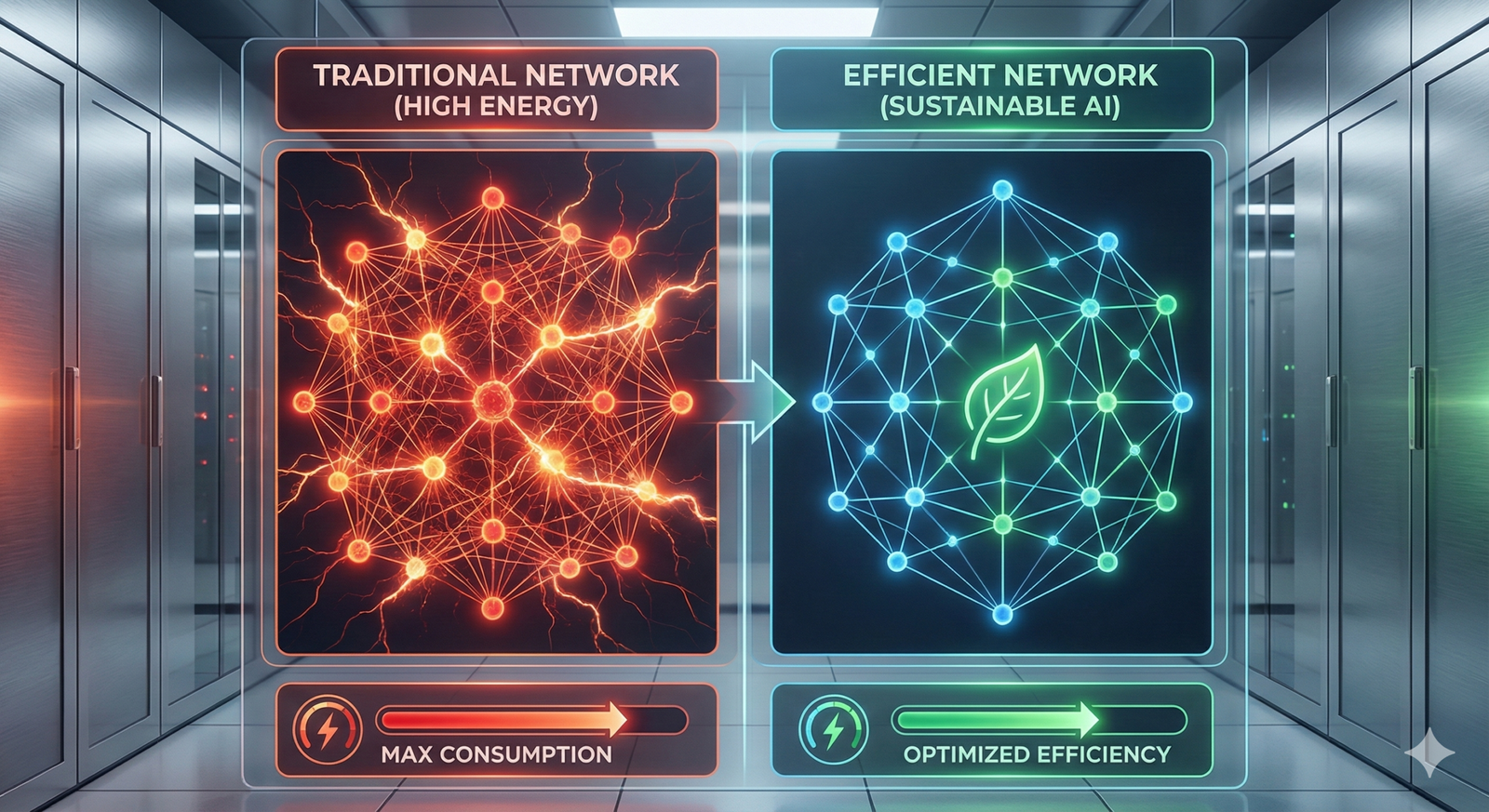

To understand where AI and the arts are heading, we must first define the mechanism of collaboration. Co-creation is distinct from simple generation. In a generative model, a user might type “cat in a hat” and accept the result. In a co-creative model, the artist engages in a dialogue with the machine.

This relationship is often described as “centaur chess”—a concept borrowed from competitive chess where a human player teamed with an AI computer consistently beats both solo supercomputers and solo grandmasters. In the arts, this translates to the “Centaur Artist”: a creator who leverages the hallucinatory power of AI to generate raw material, which is then curated, refined, and contextualized by human sensibility.

The Feedback Loop

The core of this process is the feedback loop.

- Ideation: The artist provides a sketch, a melody, or a plot outline.

- Expansion: The AI offers multiple variations, finishing the sketch or harmonizing the melody.

- Curation: The artist selects the most promising elements, rejecting the hallucinations or errors.

- Refinement: The artist manually edits the output or feeds it back into the AI with tighter constraints.

This loop solves the “blank canvas problem”—the paralysis artists often feel at the start of a project—while ensuring the final piece retains the artist’s specific voice.

Visual Arts: Beyond the Prompt

The visual arts sector has been the most visible battleground and testing laboratory for AI and the arts. Tools like Midjourney, Stable Diffusion, and Adobe’s Firefly have democratized the ability to create high-fidelity images, but professional illustrators and concept artists use these tools differently than the general public.

The “Sandwich Method” in Illustration

A common workflow adopted by concept artists in gaming and film is the “Sandwich Method.” This approach ensures that the structural integrity and intent of the piece remain human-driven.

- Layer 1 (The Bread): The artist creates a rough composition. This might be a pencil sketch, a 3D block-out in Blender, or a collage of photos. This establishes the perspective, lighting, and composition—elements AI often struggles to control precisely.

- Layer 2 (The Filling): The artist uses an image-to-image (img2img) AI workflow. They feed their sketch into the AI with a prompt describing the texture and style (e.g., “oil painting, dramatic lighting”). The AI renders the details, handling the tedious work of rendering textures like fur, metal, or foliage.

- Layer 3 (The Top Bread): The artist brings the AI output back into Photoshop or Procreate. They paint over artifacts (extra fingers, nonsensical text), color correct, and add specific details that carry narrative weight.

In practice, this allows a concept artist to generate ten high-quality variations of a character armor set in an afternoon, a task that might have previously taken a week.

In-Painting and Out-Painting

Rather than generating full images, co-creation often happens locally within a canvas.

- In-painting: An artist might paint a beautiful landscape but struggle with the figure in the foreground. They can select just the figure area and ask the AI to generate “a warrior in rusted armor,” blending it seamlessly into the hand-painted background.

- Out-painting: An artist creates a central motif but needs to extend the canvas for a different aspect ratio (e.g., turning a square Instagram post into a wide YouTube banner). The AI hallucinates the rest of the scene based on the stylistic cues of the original art.

3D and Texture Generation

In 3D modeling, AI is solving the “texture bottleneck.” Artists can now model a simple geometry and use AI to generate seamless, physically based rendering (PBR) textures—diffuse, normal, and roughness maps—from text descriptions. This allows 3D artists to focus on form and silhouette rather than spending hours painting rust onto a virtual pipe.

Music and Soundscapes: The New Jam Session

While visual art is static, music is temporal, making the integration of AI a different challenge. In the realm of AI and the arts, music tools are evolving from novelty generators into sophisticated “session musicians.”

AI as a Session Musician

Producers are using AI to fill gaps in their arrangements. If a solo producer needs a saxophone solo but cannot play the instrument, they can use audio-to-audio AI tools. By humming the melody into a microphone, the AI converts the timbre of the voice into the sound of a saxophone, preserving the human phrasing, vibrato, and timing.

This preserves the “human feel”—the slight imperfections and swing that make music groove—while changing the instrumentation.

Sample Generation and Sound Design

Sound designers are using generative audio to create new libraries of samples. instead of hunting through Splice for the perfect “cinematic boom,” a designer can describe the sound: “A deep sub-bass impact followed by shattering glass and a metallic shimmer.” The AI generates a unique waveform.

This is particularly useful for avoiding copyright strikes. Because the sample is generated from noise, it is theoretically unique, allowing composers to build soundscapes without worrying about clearing samples from existing records.

The Mastering Assistant

On the technical side, AI has become a standard second set of ears. Automated mastering services analyze a track’s frequency spectrum and dynamic range, comparing it to thousands of hit records. They then apply compression and EQ to bring the track up to commercial standards. While top-tier engineers still outperform these tools, for independent musicians, AI mastering provides a polished sound that was previously unaffordable.

Literature and Narrative: The Digital Co-Author

Text generation is perhaps the most widely accessible form of AI and the arts, yet it is also the easiest to misuse. Generating an entire novel with a single prompt usually results in bland, structural wandering. However, writers are using Large Language Models (LLMs) as highly effective developmental editors and brainstorming partners.

The “Rubber Duck” Debugging for Plot

In coding, “rubber ducking” involves explaining a problem line-by-line to an inanimate duck to find the solution. Writers use AI similarly. When stuck on a plot hole, a writer might engage the AI:

- “I have a protagonist who needs to break into a high-tech vault without triggering the alarm, but they don’t have hacking skills. What are five non-digital ways they could exploit the security?”

The AI provides a list—some cliché, some absurd, but often one or two sparks that the writer can twist into something original.

Character Voice and Dialogue

Writers use AI to test distinct character voices. By feeding a scene to an AI and asking it to rewrite the dialogue in the style of “a cynical noir detective from 1940” or “an overly enthusiastic Gen Z influencer,” authors can analyze the lexical differences and sentence structures. They rarely use the output verbatim, but the contrast helps them refine their own character sheets.

World Building at Scale

For fantasy and sci-fi authors, consistency is key. AI tools can help manage the “bible” of a fictional world. An author can input facts about their world’s economy, magic system, and geography, and then query the AI to check for contradictions. “If magic requires water to function, does it make sense for this city to be in a desert?” The AI can act as a logic checker, highlighting world-building flaws before the reader finds them.

The Ethics of Co-Creation

No discussion of AI and the arts is complete—or responsible—without addressing the ethical elephant in the room. The rapid adoption of these tools has outpaced regulation, leading to significant friction between traditional creative communities and tech developers.

The Training Data Controversy

The primary ethical concern is the origin of the data used to train these models. Many foundation models were trained on datasets scraped from the open internet, including copyrighted works of living artists, without explicit consent or compensation.

- The Artist’s Perspective: Many artists feel this is theft—high-tech laundering of their intellectual property to build a machine that competes with them.

- The Developer’s Perspective: Developers often argue this falls under “fair use,” akin to a human art student looking at thousands of paintings to learn how to paint.

As of early 2026, courts in various jurisdictions are still wrestling with these definitions. For the ethical co-creator, this means being mindful of the tools you choose. Some platforms are moving toward “opt-in” datasets or licensed training data (like Adobe’s Firefly, trained on Adobe Stock), which offers a safer ethical and legal ground for commercial work.

Copyright and Ownership

Who owns a co-created work? In the United States, the Copyright Office has taken a stance that copyright protects human authorship.

- Pure AI generation: Generally not copyrightable.

- Human-AI hybrid: Copyright applies only to the human-created elements. If you use AI to generate a background but hand-paint the characters, the characters and the overall composition are likely protected, but the raw background is not.

This nuance is critical for professional artists. If you cannot copyright your work, you cannot sell exclusive rights to a client. Therefore, professional co-creation emphasizes significant human transformation of any AI output.

Transparency and Disclosure

A growing best practice in the industry is transparency. Commercial artists are beginning to label their work with “AI-Assisted” or specifying the workflow used. This builds trust with audiences who value human effort and allows clients to understand the provenance of the files they are buying.

Tools and Platforms for Hybrid Creativity

The landscape of tools is vast, but certain platforms have emerged as industry standards for human-AI collaboration.

| Category | Tool | Best Use Case for Co-Creation |

| Visual Art | Stable Diffusion (with ControlNet) | High control over composition; allows artists to dictate pose and structure while AI handles rendering. |

| Visual Art | Adobe Photoshop (Generative Fill) | Seamless in-painting and expanding canvases; integrated into the standard professional workflow. |

| Visual Art | Krita (with AI plugins) | Open-source painting tool that allows real-time generation on top of sketches. |

| Music | Suno / Udio | Generating backing tracks or ideating melodic structures to be re-recorded by humans. |

| Music | iZotope Ozone | AI-assisted mastering and audio repair; enhances human mixes rather than creating them. |

| Writing | Sudowrite | Designed for fiction writers; offers features like “show, not tell” rewrites and sensory description expansion. |

| Writing | ChatGPT / Claude | General brainstorming, outlining, and developmental editing. |

| 3D | Blender (with AI add-ons) | Texture generation and auto-rigging of characters. |

How to Start Co-Creating: A Step-by-Step Framework

If you are an artist looking to integrate AI without losing your soul, follow this framework.

1. Identify the Bottleneck

Do not use AI for the part of the art you enjoy. If you love sketching but hate coloring, look for AI colorization tools. If you love writing dialogue but hate plotting, use AI for outlines. Outsource the drudgery, not the joy.

2. Learn “Prompt Engineering” as a Dialect

Talking to an AI is a skill. It requires precision.

- Vague: “Make a cool sci-fi city.”

- Precise: “Cyberpunk city street, low angle shot, neon lighting, wet pavement reflection, atmospheric fog, architectural style of Zaha Hadid, cinematic composition.” Learning technical terms regarding lighting, camera lenses, art styles, and materials will drastically improve your ability to control the output.

3. Iterate, Don’t Settle

Never accept the first result. Use the first result as a critique. “The lighting is wrong.” “The tone is too dark.” Feed that feedback back into the system. The best co-created works often result from dozens of generations and refinements.

4. Post-Process Heavily

Treat AI output as raw material, like clay or unhewn stone. Take it into your editing software. Color correct it. Rewrite the sentences. Chop up the audio sample. Imposing your will on the material is what makes it art.

Common Mistakes and Pitfalls

The “Slot Machine” Effect

It is easy to get addicted to the dopamine hit of generating image after image, hoping for a “lucky spin” that looks perfect. This is not creation; it is gambling. If you find yourself hitting “generate” for an hour without editing or refining, you have stopped co-creating and started consuming.

Style Inconsistency

AI models can be chaotic. If you are creating a graphic novel or a series of assets, maintaining a consistent character face or art style is difficult.

- Solution: Train your own distinct LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) models on your own previous artwork. This teaches the AI your specific style, allowing you to generate new content that looks like you made it.

Ignoring Resolution and Quality

Most AI generators output web-resolution images (e.g., 1024×1024 pixels). This is insufficient for print.

- Solution: You must learn to use AI upscaling tools (like Topaz Gigapixel or Magnific) to increase resolution while inventing plausible details, followed by manual touch-ups to ensure the new details make sense.

The Future of Creative Workflows

As we look toward the latter half of the 2020s, the distinction between “AI art” and “traditional digital art” will likely blur until it vanishes. Just as the “Paste” command was once a novelty that purists feared would ruin writing, generative fill and melodic auto-completion will become boring, standard utilities.

Custom Models for Studios

We are moving toward a future where every major design studio or game developer trains their own private AI model. A Disney or a Marvel will have an internal AI trained exclusively on their decades of proprietary art. Their artists will use this secure model to co-create, ensuring no copyright issues and perfect brand consistency.

Real-Time Co-Creation

Latency is decreasing. Soon, we will see real-time co-creation where the AI renders along with the artist’s brushstroke instantly. Imagine painting a gray block shape, and the screen immediately showing it as a photorealistic rock, updating the lighting and texture 60 times a second as you rotate or resize it.

The Return of the Physical

Paradoxically, as digital art becomes easier to mass-produce, we may see a resurgence in the value of the physical. Hand-painted oils, live acoustic performances, and handwritten manuscripts may gain a “human premium”—valued specifically because they cannot be generated by a machine.

Who This is For (and Who it Isn’t)

This approach is for:

- Commercial Artists: Graphic designers, concept artists, and copywriters who need to meet tight deadlines and produce high volumes of high-quality work.

- Indie Developers/Creators: Individuals with small budgets who need to wear multiple hats (coding, art, sound) to ship a product.

- Hobbyists: People who want to explore their imagination but lack years of technical training in specific mediums.

This approach is NOT for:

- Purists: Artists who derive their primary satisfaction from the manual execution of every stroke or note and view automation as a dilution of the craft.

- Copyright Absolutists: Those who require absolute, unshakeable copyright certainty for every pixel of their work (current laws are too fluid for guarantees).

Related Topics to Explore

- Prompt Engineering Guides: Deep dives into the syntax of talking to specific models like Midjourney or GPT-4.

- Legal Rights for Digital Artists: Resources on how to register hybrid works and protect your style from being scraped.

- The History of Generative Art: From the plotters of the 1960s to the GANs of the 2010s.

- AI Model Fine-Tuning: Tutorials on how to train a model on your own dataset.

- Digital Watermarking: Tools like Glaze and Nightshade that protect art from AI training.

Conclusion

The intersection of AI and the arts is not a finish line; it is a new medium. History shows that technology rarely subtracts from art; it expands it. The camera did not kill painting; it freed painting from the need to be realistic, leading to Impressionism and Cubism. Synthesizers did not kill the orchestra; they gave birth to electronic music, hip-hop, and pop.

We are currently at the “camera moment” for intelligence. The artists who thrive in this new era will not be the ones who type a prompt and walk away. They will be the co-creators—the ones who see AI as a powerful engine that requires a human hand on the steering wheel. They will use these tools to tell deeper stories, compose richer symphonies, and paint vaster worlds than one human lifetime would previously allow. The future of art is not human vs. machine; it is human plus machine.

Next Steps: Choose one part of your workflow that feels tedious or repetitive. Find an AI tool designed for that specific task, and dedicate one afternoon to experimenting with it. Focus on how you can guide the output to match your vision, rather than letting the tool dictate the result.

FAQs

Can I copyright art I make with AI?

In the US, you generally cannot copyright the raw output of an AI. However, if you significantly modify the output—through painting, collage, or editing—you may be able to copyright the human-created aspects of the work. This is a developing legal area, so consult an IP lawyer for commercial projects.

Is using AI in art cheating?

“Cheating” implies breaking the rules of a game. Art has no fixed rules. If your goal is to express an idea or emotion, the tools you use are secondary. However, if you claim you hand-painted something that was generated, that is dishonest. Transparency is the key to ethical usage.

Will AI replace human artists?

AI will likely replace tasks, not artists. Low-level, repetitive tasks (like rotoscoping, stock asset generation, or basic copy editing) are vulnerable. However, roles requiring high-level direction, taste, emotional resonance, and cultural context are becoming more valuable. Artists who adapt to use AI will likely replace those who do not.

How do I stop my art from being used to train AI?

Tools like Glaze and Nightshade are developed by researchers to add invisible noise to your images. This noise confuses AI models if they try to train on your work, effectively “poisoning” the data regarding your style. You can apply these tools before posting your work online.

What is the best AI tool for beginners?

For visual art, Midjourney (via Discord) is often cited as having the highest quality “out of the box” aesthetics for beginners. For writing, ChatGPT or Claude are the most accessible. For image editing, Adobe Firefly (integrated into Photoshop) is the most user-friendly for existing designers.

Does AI art steal from other artists?

AI models learn by analyzing patterns in billions of images, many of which are copyrighted. They do not “collage” existing images, but they do learn styles. If you prompt an AI to “paint like Greg Rutkowski,” it mimics his style using those learned patterns. This mimicry is the source of significant ethical and legal debate regarding artists’ rights.

Can AI generate text on images correctly now?

Yes, newer models (like DALL-E 3, Midjourney v6, and Flux) have significantly improved at rendering readable text within images. While not perfect, they can now handle signs, labels, and logos much better than models from 2023.

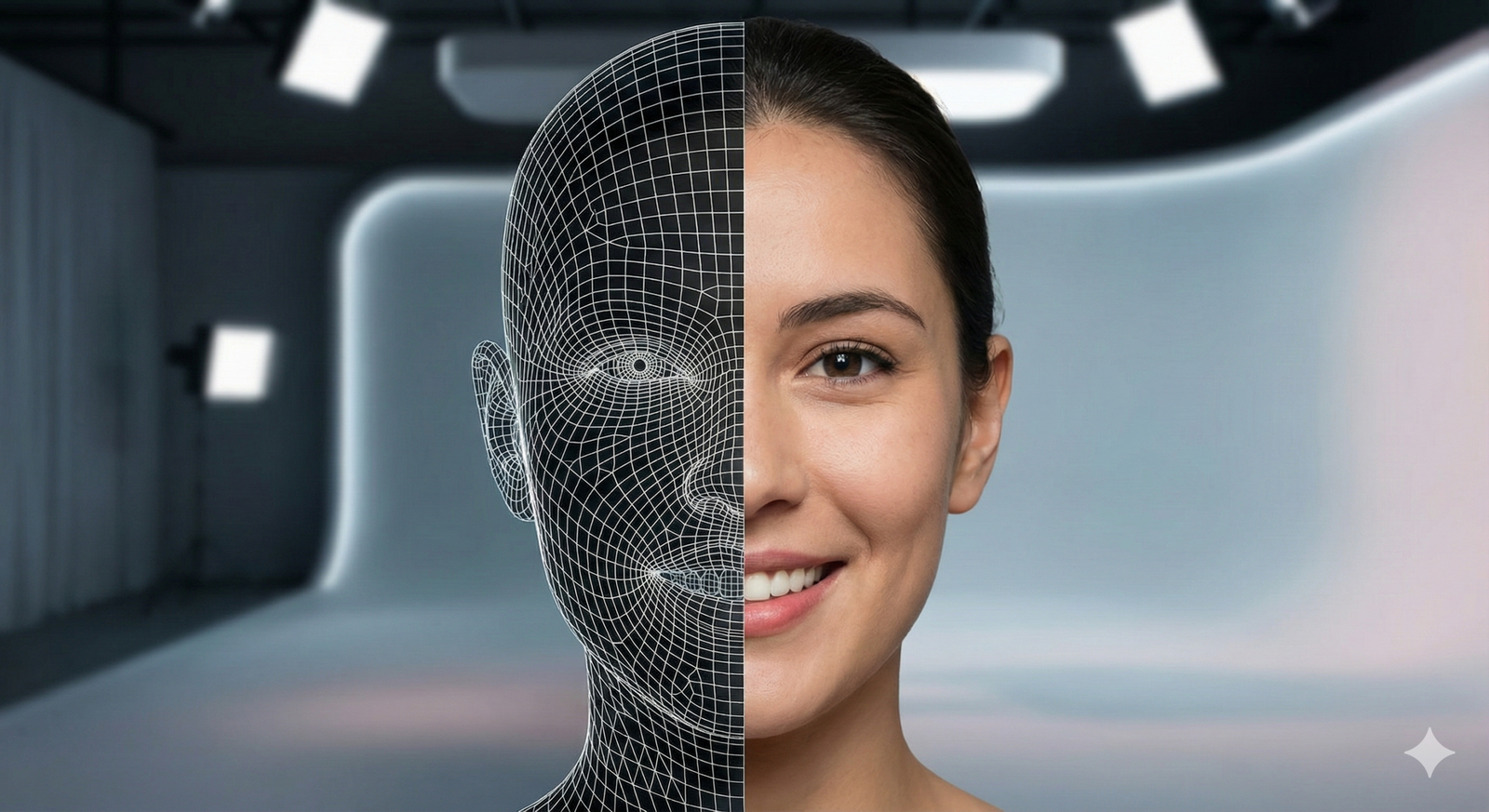

How can I tell if an image is AI-generated?

Look for inconsistencies: hands with too many fingers, nonsensical text in the background, jewelry that melts into skin, or hair that defies physics. Also, AI images often have a specific “glossy” or overly smooth texture, though this is becoming harder to spot as models improve.

References

- U.S. Copyright Office. (2023). Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence. Retrieved from https://www.copyright.gov/ai/

- Adobe. (2025). Adobe Firefly: Generative AI for Creators. Retrieved from https://www.adobe.com/products/firefly.html

- Glaze Project. (2024). Protecting Artists from Style Mimicry. University of Chicago. Retrieved from https://glaze.cs.uchicago.edu/

- Stability AI. (2024). Stable Diffusion 3 Technical Report. Retrieved from https://stability.ai/

- Epstein, Z., et al. (2023). Art and the science of generative AI. Science. Retrieved from https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adh4451

- Suno AI. (2024). Building a future where anyone can make music. Retrieved from https://suno.com/about

- Authors Guild. (2024). Artificial Intelligence and the Writing Life. Retrieved from https://www.authorsguild.org/

- Blender Foundation. (2025). Blender 4.2 Release Notes: AI Integration. Retrieved from https://www.blender.org/