The rapid integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) into the global economy promises unprecedented efficiency and innovation. However, it also presents a profound challenge: the potential for significant labor market disruption. Unlike previous industrial revolutions that primarily automated physical tasks, the AI revolution—driven by generative models and advanced machine learning—is poised to automate cognitive and creative tasks as well. This shift necessitates a fundamental rethinking of the social contract.

Managing AI job displacement is not merely a technical challenge; it is a societal imperative. It requires a comprehensive suite of social policies designed not just to cushion the blow of job loss, but to actively facilitate transitions, empower workers, and redistribute the economic gains of automation. This guide explores the policy frameworks, from safety nets to education reform, that governments and organizations must consider to navigate this transition equitably.

Key Takeaways

- The Scope is Broader: AI displacement affects white-collar and creative sectors, not just manual labor, requiring new policy paradigms.

- Beyond Cash Handouts: While income support is vital, effective policy must prioritize “Active Labor Market Policies” (ALMPs) like reskilling and job placement.

- Funding the Transition: Innovative fiscal mechanisms, such as “robot taxes” or AI-specific levies, are being debated to fund social programs.

- Rights in the Algorithm: protecting workers involves regulating “algorithmic management” and ensuring human oversight in hiring and firing.

- Lifelong Learning: Education systems must shift from a “front-loaded” model to a continuous, lifelong learning infrastructure.

Scope of This Guide

In this guide, “displacement” refers to the involuntary loss of employment due to automation or AI integration. “Social policies” refers to government and institutional frameworks (laws, benefits, regulations) designed to support societal well-being. This article focuses on systemic policy responses rather than individual career advice.

The Nature of the Challenge: Why This Time is Different

To design effective policies for managing AI job displacement, we must first understand how AI differs from previous waves of automation. Historically, technology created more jobs than it destroyed by lowering costs and increasing demand. However, the speed and breadth of AI adoption pose unique risks.

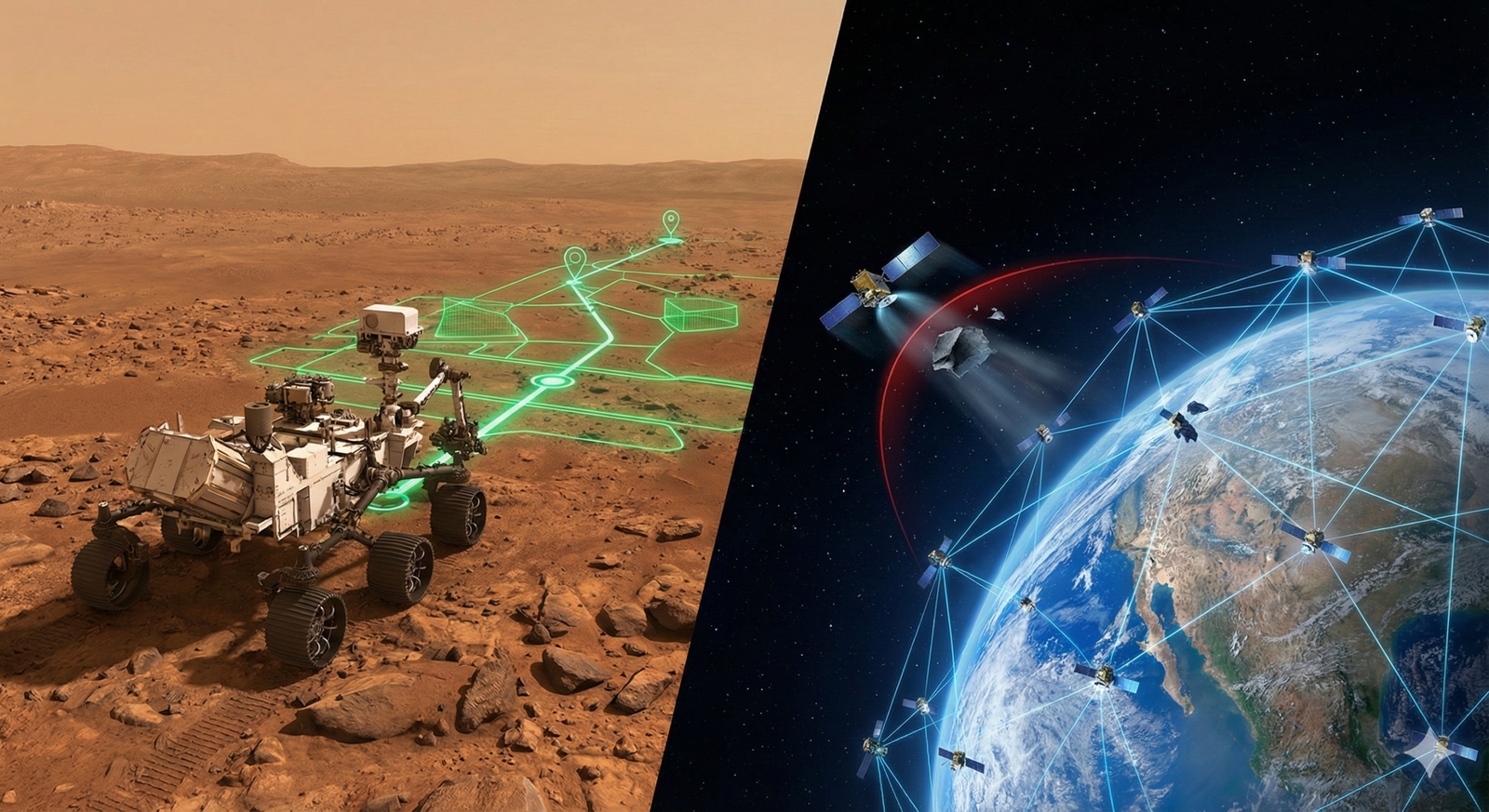

Cognitive Automation vs. Physical Automation

The Industrial Revolution replaced muscle with machines. The Information Revolution replaced calculation with computers. The AI Revolution is replacing cognition with algorithms. This means that high-skill, high-wage jobs in law, finance, coding, and journalism are now exposed to automation pressures previously reserved for manufacturing.

The Speed of Transition

The rate at which AI models improve—scaling in capability arguably faster than human adaptability—creates a “transition friction.” Even if new jobs are created, displaced workers may not have the time or resources to acquire the necessary skills to fill them. Structural unemployment occurs when there is a mismatch between the skills workers possess and the skills the economy demands.

Who is Most at Risk?

While predictions vary, organizations like the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the OECD suggest that routine cognitive tasks are most vulnerable.

- Administrative Support: Data entry, scheduling, and basic customer service.

- Junior Professional Services: Legal research, basic coding, and financial analysis.

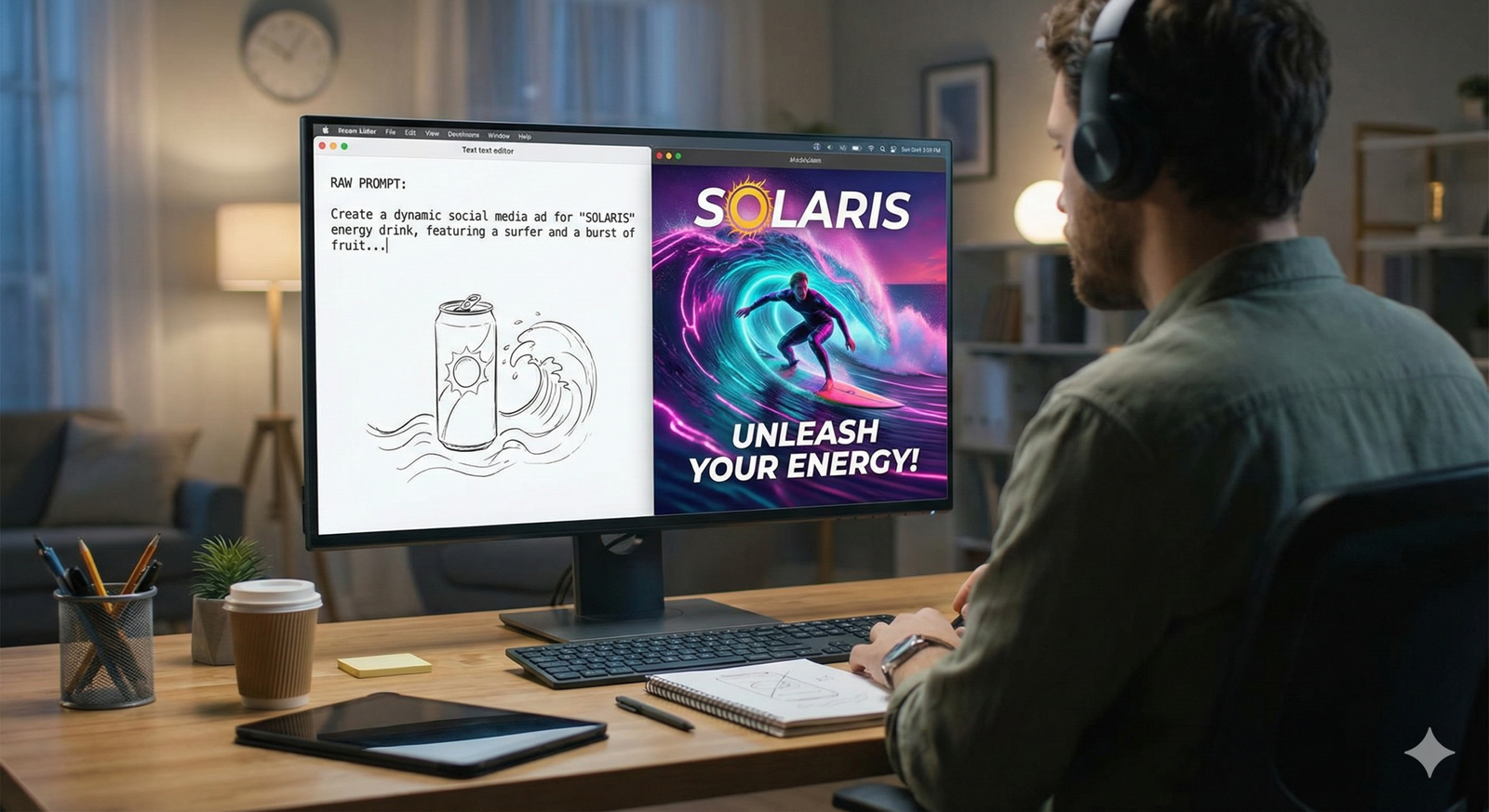

- Creative Industries: Copywriting, graphic design, and translation.

Conversely, jobs requiring high emotional intelligence, complex physical dexterity in unstructured environments (e.g., plumbing, elder care), and high-level strategic decision-making remain more resilient.

Rethinking Social Safety Nets: The Foundation of Security

When displacement occurs, the immediate policy priority is preventing poverty and maintaining aggregate demand. Traditional unemployment insurance, often tied to full-time employment and limited in duration, may be insufficient for an era of fluid, gig-based, or intermittent work driven by AI.

Universal Basic Income (UBI)

Universal Basic Income is frequently cited as a primary solution for managing AI job displacement. UBI involves a periodic cash payment delivered to all on an individual basis, without means test or work requirement.

- The Argument for UBI: It provides a guaranteed floor of financial security, allowing workers to retrain, start businesses, or engage in care work without the fear of destitution. It decouples survival from traditional employment.

- The Argument Against UBI: Critics argue it is prohibitively expensive and may discourage workforce participation. There are also concerns that it could lead to the dismantling of other essential targeted welfare programs.

- Pilots and Evidence: Various trials (e.g., in Finland, Canada, and the US) have shown mixed results regarding employment effects but generally positive impacts on mental health and community stability.

Universal Basic Services (UBS)

An alternative or complement to UBI is Universal Basic Services. Instead of cash, the government guarantees free access to life’s necessities: housing, transport, high-speed internet, and education.

- Relevance to AI: UBS lowers the cost of living, making lower wages (which might result from AI devaluing human labor in some sectors) more livable. It ensures that displaced workers remain connected to the infrastructure needed to find new work (e.g., internet access).

Portable Benefits Systems

As AI fragments traditional employment into “tasks” and gig work, social benefits must become portable. A portable benefits system allows benefits (healthcare, retirement, training funds) to be tied to the individual worker rather than the employer.

- Implementation: Workers could have a “benefits account” into which every employer contributes a pro-rated amount based on hours worked or tasks completed. This ensures that a freelancer working for five different AI platforms still accumulates a safety net.

Active Labor Market Policies (ALMPs): Bridging the Skills Gap

Passive benefits keep people fed; active policies get them back to work. Managing AI job displacement effectively requires a massive scaling of Active Labor Market Policies (ALMPs).

Government-Funded Reskilling and Upskilling

The most critical ALMP is training. Market-led training often fails because companies are reluctant to train employees who might leave (the “free rider” problem).

- Individual Learning Accounts (ILAs): Governments can provide every citizen with an annual stipend specifically for accredited training. Singapore’s “SkillsFuture” initiative is a leading model, providing credit to citizens to use for approved courses.

- Targeted Reskilling: analyzing labor market data to identify growing sectors (e.g., green energy, healthcare, AI ethics) and subsidizing training specifically for those pathways.

Job Guarantee Programs

For those who cannot easily be reskilled or where private sector demand is insufficient, some economists advocate for a Job Guarantee.

- Concept: The government acts as an “employer of last resort,” offering a job at a living wage to anyone willing and able to work.

- AI Context: These jobs could focus on areas where human interaction is premium and automation is difficult: community care, environmental restoration, and public art. This ensures social inclusion and maintains the psychological benefits of work.

Hiring Subsidies and Transition Support

To encourage companies to hire displaced workers, governments can offer temporary wage subsidies. This lowers the risk for employers to take on older workers or those pivoting from declining industries. Career counseling services, enhanced by AI matching algorithms, can also help navigate complex job markets.

Funding the Transition: Who Pays?

Implementing UBI, UBS, or massive reskilling programs requires significant capital. A central debate in managing AI job displacement is how to tax the new wealth generated by automation.

The “Robot Tax” Debate

The idea of a “robot tax” suggests taxing companies that replace human workers with automated systems.

- Pros: It slows down the pace of automation to a manageable rate and generates revenue directly from the source of displacement to fund social programs.

- Cons: It is difficult to define what a “robot” or “AI” is for tax purposes. Does a spreadsheet count? Critics argue it penalizes efficiency and innovation, potentially driving companies to relocate to jurisdictions without such taxes.

Excess Profits and Digital Services Taxes

A more feasible approach may be taxing the “excess profits” of highly automated firms. Since AI allows companies to scale revenue without scaling headcount, corporate tax systems based on physical presence or headcount are becoming obsolete.

- Global Minimum Tax: International cooperation (like the OECD’s Pillar Two framework) is essential to prevent a race to the bottom, ensuring that multinational AI giants contribute to the social safety nets of the countries where they operate.

Data Levies

Since AI models are trained on public data (the “commons”), some policymakers propose a levy on data extraction. If public data fuels private profit, a portion of that profit should return to the public purse to fund transition assistance.

Regulatory Guardrails: Protecting Rights in the Workplace

Displacement isn’t just about losing a job; it’s about the degradation of the jobs that remain. Policy must address the power dynamic between workers and AI systems.

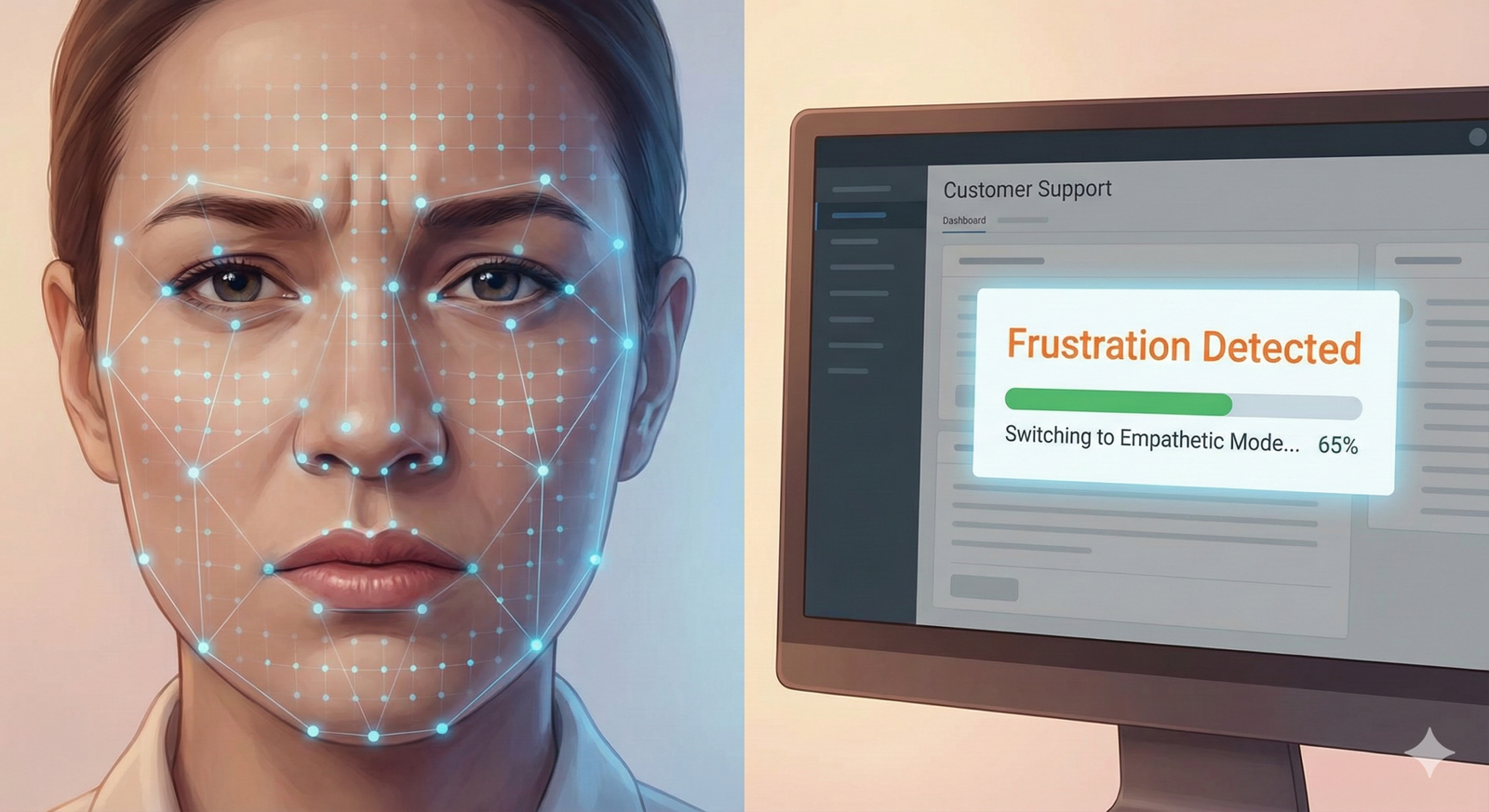

Regulating Algorithmic Management

“Algorithmic management” refers to the use of AI to direct, evaluate, and discipline workers (common in gig economy apps and warehouses).

- Transparency: Workers should have the right to know if they are being managed by an AI and understand the criteria used for evaluation.

- Human-in-the-Loop: Decisions regarding firing or significant disciplinary action should require human review. Automated terminations without appeal should be legally prohibited.

Addressing Bias in Hiring

AI is increasingly used to screen resumes and conduct interviews. If these systems are biased, they can systematically exclude certain demographics from the workforce, exacerbating displacement inequality.

- Auditing Standards: Governments must mandate regular, independent audits of hiring algorithms to check for disparate impact based on race, gender, or age.

- Explainability: Rejected candidates should have the right to a basic explanation of why the system rejected them, allowing for recourse if the reasoning is flawed.

The Right to Disconnect

As AI tools make work accessible 24/7 and blur the lines between office and home, protecting worker mental health is crucial. “Right to Disconnect” laws, which forbid employers from requiring communications outside of working hours, help prevent burnout in an AI-accelerated environment.

The Role of Education Systems: A Long-Term Strategy

While ALMPs address the current workforce, education policy must look 20 years ahead. Managing AI job displacement requires inoculating the next generation against obsolescence.

Shifting Focus: From Rote to Resilience

Traditional education often emphasizes memorization and standardized testing—skills that AI excels at. Curricula must shift toward:

- Critical Thinking and Synthesis: The ability to evaluate AI outputs and connect disparate ideas.

- Emotional Intelligence (EQ): Empathy, negotiation, and leadership are difficult to automate.

- Agility: Teaching students how to learn, rather than what to know.

Integrating AI Literacy

Just as computer literacy became mandatory in the 90s, AI literacy is now essential. Every student should understand how LLMs work, their limitations, and the ethics of their use. This demystifies the technology and empowers future workers to use AI as a tool rather than seeing it solely as a rival.

The Decline of the “Degree Signal”

As AI helps non-experts perform expert tasks (e.g., coding assistants), the premium on expensive 4-year degrees may diminish for some roles. Policy should support alternative credentialing, micro-credentials, and apprenticeships that value demonstrated skill over prestige.

Corporate Responsibility vs. State Intervention

Governments cannot manage this transition alone. The private sector, which benefits from the efficiency gains of AI, bears a responsibility to its workforce.

The “Retrain to Retain” Model

Forward-thinking companies are realizing that firing and re-hiring is expensive and damages morale. “Internal mobility” platforms, powered by AI, can identify employees in at-risk roles and match them to open internal positions that require similar soft skills, bridging the technical gap with training.

- Policy Incentive: Tax credits can be offered to corporations that retrain employees for new roles rather than laying them off.

Worker Consultation

Policies should mandate that Worker Councils or unions be consulted before major AI implementations. This “co-determination” allows workers to provide input on how tools are deployed, often identifying efficiencies that management might miss and reducing resistance to change.

Common Pitfalls in Policy Design

In the rush to regulate, policymakers often make mistakes. Here are common traps to avoid when managing AI job displacement.

Pitfall 1: Protecting Jobs Instead of Workers

Trying to ban automation to “save jobs” is usually futile and economically damaging. Policies should focus on protecting people (income, healthcare, dignity) rather than preserving obsolete job descriptions.

Pitfall 2: One-Size-Fits-All Training

Not everyone can “learn to code.” Reskilling programs often fail because they push everyone toward technical fields. Effective policy supports transitions into the care economy, trades, and arts, not just software engineering.

Pitfall 3: Ignoring Regional Disparities

AI impact will be uneven. Tech hubs may boom while manufacturing or administrative centers decline. Place-based policies (investment zones, relocation assistance) are necessary to prevent the hollowing out of specific communities.

Who This Is For (and Who It Isn’t)

This guide is for:

- Policymakers and Civil Servants: Seeking frameworks to draft legislation regarding labor and technology.

- Business Leaders and HR Executives: Looking to understand the regulatory horizon and ethical transition strategies.

- Labor Unions and Advocates: Needing arguments and structures for collective bargaining in the AI era.

- Concerned Citizens: Wanting to understand the future of the social safety net.

This guide is NOT for:

- Technical Developers: Looking for code or architectural advice on building AI models.

- Individual Job Seekers: Looking for specific resume tips or job interview hacks (though the “Reskilling” section is relevant).

Global Perspectives: Differing Approaches

Different regions are adopting distinct strategies for managing AI job displacement.

| Region | Primary Focus | Key Mechanisms |

| European Union | Regulation & Rights | The AI Act; strong GDPR protections; focus on worker privacy and algorithmic transparency. |

| United States | Innovation & Safety Nets | Market-driven adaptation; debates over expanding trade adjustment assistance; pilot UBI programs at state levels. |

| Scandinavia | Flexicurity | High taxes funding robust social safety nets combined with easy hiring/firing rules; heavy investment in state-funded retraining. |

| China | Strategic Planning | State-directed investment in AI infrastructure; focus on education reform to support national tech goals. |

Related Topics to Explore

For a deeper understanding of the ecosystem surrounding AI and labor, consider exploring these related topics:

- The Ethics of Generative AI: Intellectual property rights and creative labor.

- Algorithmic Bias: How AI models perpetuate historical discrimination.

- The Gig Economy Evolution: How platforms are changing the definition of “employee.”

- Human-Centric AI Design: Building tools that augment rather than replace.

- Sustainable AI: The environmental cost of training large models.

- Digital Sovereignty: Nations controlling their own data and AI infrastructure.

Conclusion

Managing AI job displacement is the defining economic challenge of our time. The “invisible hand” of the market alone will not be sufficient to ensure a fair transition; it requires the “visible hand” of thoughtful, proactive social policy.

We are at a crossroads. One path leads to a future of extreme inequality, where the owners of AI capital capture the vast majority of wealth while a displaced workforce struggles with structural unemployment. The other path uses the abundance generated by AI to fund a robust social floor, reinvigorate the care economy, and empower humans to pursue work that is creative, interpersonal, and meaningful.

The difference between these futures lies in the policies we choose today. Governments must move beyond reactive measures and build a twenty-first-century safety net that is flexible, inclusive, and funded by the very efficiencies AI creates.

Next Step: If you are a business leader, audit your current workforce for automation risk and investigate “internal mobility” tax incentives in your jurisdiction; if you are a citizen, advocate for portable benefits and lifelong learning accounts.

FAQs

What is the difference between job displacement and job augmentation?

Job displacement occurs when a technology renders a role obsolete, leading to job loss. Job augmentation happens when technology automates specific tasks within a job, allowing the worker to be more productive or focus on higher-value work. Policy for displacement focuses on safety nets and rehiring, while policy for augmentation focuses on upskilling workers to use new tools.

Can Universal Basic Income (UBI) really solve AI unemployment?

UBI is not a silver bullet, but it provides a necessary foundation. It addresses the income volatility that comes with displacement and gig work. However, without accompanying policies like rent control, public services (UBS), and reskilling programs, UBI alone may not be sufficient to ensure a high quality of life or social inclusion.

What is a “Robot Tax”?

A “Robot Tax” is a proposed fiscal policy where companies pay a tax based on the use of automated systems that replace human workers. The revenue is intended to fund social programs for displaced workers. Critics argue it is hard to implement and stifles innovation, while proponents say it is necessary to slow automation and redistribute wealth.

How does “Algorithmic Management” affect workers?

Algorithmic management uses data and AI to track, evaluate, and direct workers. Without regulation, it can lead to excessive surveillance, stress, and unfair termination. Social policies are increasingly focusing on “digital rights” at work, ensuring human oversight in critical employment decisions.

Which industries are most at risk of AI displacement?

Unlike previous automation waves, AI heavily impacts cognitive sectors. Administrative support, customer service, translation, writing, basic coding, and junior financial or legal analysis are at high risk. Manual trades like plumbing, electricians, and personalized healthcare are currently more resilient due to the complexity of the physical environment.

What is the “Skills Gap”?

The skills gap refers to the mismatch between the skills workers currently possess and the skills employers need. In the AI era, this gap widens quickly. Workers may be skilled in manual processes or legacy software, while employers need skills in AI prompting, data analysis, and complex problem-solving.

How can education systems adapt to AI?

Education needs to move away from rote memorization, which AI does better than humans. Instead, it should focus on “soft skills” (empathy, leadership), critical thinking, and adaptability. Lifelong learning models, where adults return to education periodically, are replacing the “one-and-done” degree model.

Is AI job displacement a global issue?

Yes, but it affects regions differently. Developed nations with high wage costs have a higher incentive to automate. Developing nations may lose the “outsourcing” advantage as AI can do cheap cognitive labor (like call centers) locally in developed markets. Global policy cooperation is needed to manage these shifts.

References

- OECD. (2024). The Impact of AI on the Workplace: Evidence from the OECD AI Surveys. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2023). Generative AI and Jobs: A global analysis of potential effects on job quantity and quality. ILO Working Paper. https://www.ilo.org

- World Economic Forum. (2023). The Future of Jobs Report 2023. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org

- Acemoglu, D., & Restrepo, P. (2020). Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets. Journal of Political Economy. University of Chicago Press.

- European Parliament. (2024). The Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act). Official Journal of the European Union.

- Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI). (2024). AI Index Report 2024. Stanford University. https://hai.stanford.edu

- SkillsFuture Singapore. (n.d.). About SkillsFuture. Government of Singapore. https://www.skillsfuture.gov.sg

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2023). Generative AI and the Future of Work in America. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com

- Brundage, M., et al. (2018). The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation. Future of Humanity Institute. https://www.fhi.ox.ac.uk

- Standing, G. (2017). Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen. Penguin Books. (Contextual reference for UBI frameworks).