Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical or legal advice. It explores the ethical, social, and governance frameworks surrounding the use of automation and artificial intelligence in healthcare settings. For specific medical guidance, consult a qualified healthcare professional. For legal compliance regarding medical technology, consult a legal expert specializing in healthcare regulations.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and automated systems into healthcare is arguably one of the most transformative shifts in the history of medicine. From algorithms that detect early signs of cancer in radiology scans to chatbots that triage patients in emergency rooms, the promise of automation is immense: greater efficiency, higher accuracy, and democratized access to care. However, as we delegate more high-stakes choices to machines, we face a complex web of ethical dilemmas.

Automating healthcare decisions is not merely a technical upgrade; it is a fundamental shift in how care is delivered, who is responsible for outcomes, and how the sanctity of the doctor-patient relationship is preserved. As of January 2026, healthcare institutions and regulators worldwide are grappling with how to harness these tools without compromising human rights or patient safety.

Key Takeaways

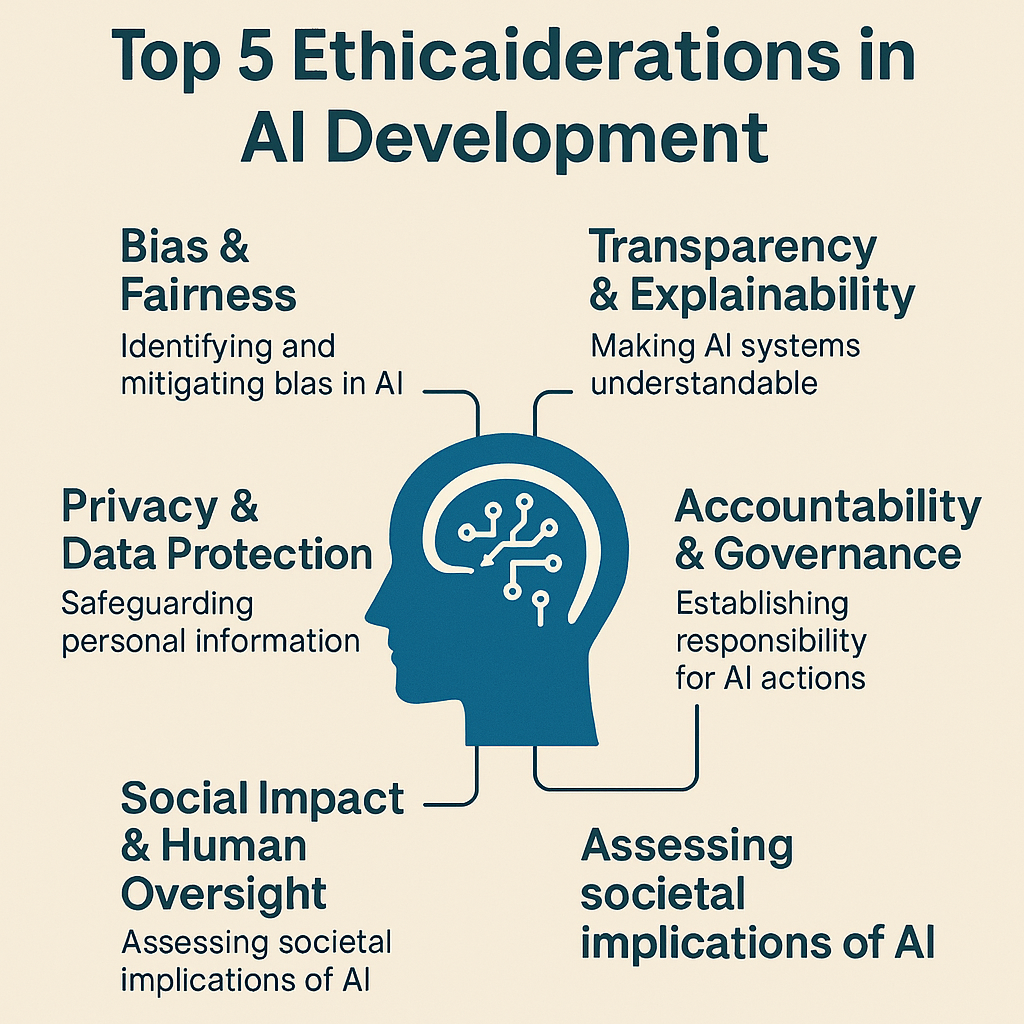

- Accountability Gap: Determining liability when an algorithm makes an error—whether it lies with the developer, the hospital, or the clinician—remains a primary legal and ethical challenge.

- Bias and Equity: Automation can scale existing inequalities if training data reflects historical biases, potentially leading to worse outcomes for marginalized demographics.

- The “Black Box” Problem: Many advanced models cannot explain why they reached a specific conclusion, complicating informed consent and clinical trust.

- Human-in-the-Loop: Ethical deployment almost always requires human oversight, yet “automation bias” can cause clinicians to over-rely on machine outputs.

- Privacy Beyond HIPAA: Modern AI can infer sensitive health conditions from non-health data, requiring a re-evaluation of privacy standards.

Scope of This Guide

In this guide, “automating healthcare decisions” refers to the use of algorithms, AI, and machine learning (ML) models to assist or replace human judgment in clinical settings (diagnosis, treatment recommendations), administrative tasks (insurance claims, scheduling), and operational logistics (resource allocation).

Out of scope: This guide does not cover the technical engineering of these models (coding, architecture) or purely mechanical automation (robotic surgery arms controlled entirely by humans), except where autonomous decision-making is involved.

1. The Core Tension: Efficiency vs. Humanity in Medicine

The fundamental ethical tension in automating healthcare decisions lies between the drive for efficiency and the imperative of human-centric care. Algorithms are designed to optimize metrics—speed, cost, accuracy rates—whereas medicine is deeply rooted in empathy, context, and the nuance of individual human experience.

The Promise of Automation

In an ideal scenario, automated systems act as a “second pair of eyes.” They can process vast datasets that no single human brain could encompass, identifying patterns in genomic data or flagging drug interactions that a tired physician might miss. This can lead to earlier interventions and more personalized treatment plans, theoretically saving lives and resources.

The Risk of Dehumanization

The ethical risk arises when the patient becomes a data point rather than a person. If a system automatically denies an insurance claim based on a statistical probability of recovery, or if a triage algorithm prioritizes patients based solely on vitals without seeing their pain, the system strips away the compassionate discretion that defines quality care. There is a tangible fear that “care” is being replaced by “processing,” leaving patients feeling alienated and unheard.

2. Algorithmic Bias and Health Equity

One of the most urgent ethical considerations is the potential for automated systems to perpetuate or even exacerbate health disparities. AI systems are only as good as the data they are trained on, and historical health data is frequently riddled with bias.

The Data Representation Problem

If an algorithm is trained primarily on data from academic medical centers in wealthy urban areas, it will learn the health patterns of that specific demographic—often Caucasian, insured, and affluent. When that same model is applied to a rural or minority population, its predictions may be inaccurate.

- Example in Practice: Dermatological AI trained mostly on light skin tones may fail to recognize skin cancer signs on darker skin, leading to delayed diagnoses and higher mortality rates for Black or Brown patients.

- Socioeconomic Proxies: Algorithms often use “healthcare cost” as a proxy for “health need.” However, due to systemic barriers, marginalized groups often spend less on healthcare even when they are sicker. An automated system might therefore classify them as “healthier” and deny them necessary extra support, as documented in seminal studies regarding population health management.

Impact on Vulnerable Populations

The ethical imperative here is distributive justice. If automation benefits the majority but harms a minority, it violates the core medical ethic of justice. Automating decisions regarding organ transplant lists, ICU bed allocation, or insurance coverage must be rigorously audited to ensure they do not systematically disadvantage people based on race, gender, disability, or economic status.

Mitigation Strategies

To address this, developers and healthcare providers must:

- Auditing Datasets: Rigorously screen training data for representation gaps before a model is built.

- Algorithmic Impact Assessments: Conduct simulations to see how the model affects different demographic groups before deployment.

- Continuous Monitoring: Track real-world outcomes by demographic to catch drift or bias immediately.

3. The “Black Box” Problem and Transparency

Trust is the currency of healthcare. Patients trust doctors to act in their best interest, and doctors trust their training and tools. However, many modern AI tools, particularly Deep Learning (DL) models, operate as “black boxes.”

What is the Black Box?

A black box model takes inputs (e.g., patient symptoms, lab results) and produces an output (e.g., a diagnosis of pneumonia) without revealing the internal logic or specific features that led to that decision. The relationships between variables are so complex that even the developers cannot fully explain how the model arrived at the answer.

The Ethical Conflict with Informed Consent

Informed consent requires that a patient understands the risks, benefits, and alternatives of a medical procedure. If a doctor recommends a surgery based on an AI prediction, but cannot explain why the AI predicts the surgery is necessary, can the patient truly give informed consent?

- The Clinician’s Dilemma: A doctor might be faced with an AI suggestion that contradicts their intuition. If the AI is opaque, the doctor cannot validate the reasoning. If they follow the AI and it’s wrong, they harm the patient. If they ignore the AI and it was right, they also harm the patient. Transparency is essential for clinical validation.

Explainable AI (XAI) as an Ethical Requirement

There is a growing ethical consensus that high-stakes healthcare AI must be “explainable” or “interpretable.” This means the system should provide:

- Global Interpretability: Understanding the general rules the model follows.

- Local Interpretability: Understanding why a specific decision was made for a specific patient (e.g., “The model flagged sepsis risk because of the rapid drop in blood pressure combined with elevated white blood cell count”).

4. Accountability and Liability: Who is Responsible?

When a human doctor makes a mistake, the frameworks for malpractice and liability are well-established. When an automated system makes a mistake, the lines of responsibility blur.

The Liability Web

- The Developer: Is the software company liable for a coding error or a biased dataset?

- The Healthcare Provider (Hospital): Is the hospital liable for procuring and deploying the tool?

- The Clinician: Is the doctor liable for trusting the tool, or for overriding it?

Automation Bias and “Rubber Stamping”

A major ethical risk is automation bias, where humans tend to favor suggestions from automated decision-making systems and ignore contradictory information, even if it is correct. In a high-pressure environment like an Emergency Department, a doctor might mentally “offload” the decision to the AI to save cognitive energy. If the AI misses a diagnosis and the doctor rubber-stamps it, the doctor is typically legally liable, as the “human-in-the-loop.” However, ethically, the system design contributed to the error by creating a reliance that the human could not realistically police.

The Moral Crumple Zone

Researchers refer to the human operator as the “moral crumple zone”—the person who takes the blame for the failure of a complex technological system. Ethical automation requires that we do not unfairly burden clinicians with supervising machines they do not understand, while simultaneously stripping them of the agency to make independent decisions.

5. Patient Autonomy and the Doctor-Patient Relationship

Patient autonomy is the right of patients to make decisions about their own medical care without their healthcare provider trying to influence the decision. Automation introduces a third party—the algorithm—that can subtly erode this autonomy.

Nudging and Paternalism

Automated systems often use “nudges” to guide behavior. For example, an app might nag a diabetic patient to exercise or take medication. While benevolent in intent, this can cross into paternalism if the system manipulates the patient or overrides their preferences. Furthermore, if an AI system predicts a patient has a low probability of adhering to a treatment plan, a provider might unconsciously (or consciously) withhold that treatment option. This preemptive denial based on a statistical prediction violates the patient’s right to try.

Erosion of Empathy

The doctor-patient relationship relies on empathy—the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. AI cannot empathize. If a consultation is dominated by a doctor staring at a screen and inputting data to satisfy an algorithm, the therapeutic value of the human connection is lost. Studies have shown that patients who feel heard have better outcomes. If automation turns the encounter into a transactional data exchange, the quality of care diminishes, regardless of the diagnostic accuracy.

6. Privacy and Data Security Risks

Healthcare data is among the most sensitive data in existence. While regulations like HIPAA (in the US) and GDPR (in the EU) protect medical records, AI introduces new privacy challenges that existing laws may not fully cover.

The Risk of Re-identification

AI models require massive datasets. Often, data is “anonymized” before training. However, AI is incredibly good at triangulation. By cross-referencing anonymized health data with public datasets (like voting records or social media), it is sometimes possible to re-identify individuals, exposing their private medical history.

Inference of Sensitive Attributes

AI can infer sensitive information from seemingly harmless data.

- Example: An algorithm analyzing typing patterns (keystroke dynamics) to detect early Parkinson’s disease might be deployed on a standard smartphone app. A user might download a game, unaware that their motor skills are being analyzed for neurological conditions.

- Ethical Question: Does a person have a “right not to know”? Or a right not to be diagnosed without consent? If an automated system infers a user has early-stage Alzheimer’s based on their shopping habits, does it have a duty to warn? Does it have a right to sell that inference to an insurance company?

Data Security vs. Model Utility

There is often a trade-off between privacy and utility. Federated Learning (where models are trained on decentralized devices without moving the data) is emerging as a solution, but it is not yet the standard. Until then, the centralization of massive health lakes creates a tempting target for cyberattacks.

7. Safety, Reliability, and Hallucination

In generative AI and Large Language Models (LLMs) used for summarising patient notes or suggesting diagnoses, hallucination is a critical safety risk.

The Consequence of False Confidence

An AI model might confidently assert a medical fact that is completely fabricated. Unlike a human student who might say “I’m not sure,” an algorithm often presents errors with the same statistical confidence as facts. In a clinical setting, a hallucinated drug dosage or a fabricated allergy in a patient summary could be fatal.

Robustness and Domain Shift

An AI model trained on data from 2020 might fail when applied to data in 2026 because medical protocols, drug names, and disease strains change. This is known as domain shift or model drift.

- Ethical Obligation: It is unethical to deploy a “set it and forget it” model in healthcare. There is a continuous obligation to monitor, retrain, and validate the model against current medical standards.

8. Regulatory Landscapes and Compliance

Navigating the ethics of automation is not just a philosophical exercise; it is a legal necessity. As of January 2026, the regulatory landscape is shifting from voluntary guidelines to strict enforcement.

The European Union (EU AI Act)

The EU AI Act classifies many healthcare AI systems (like those used for triage or robotic surgery) as “High Risk.” This designation imposes strict obligations:

- High-quality data governance.

- Detailed technical documentation.

- Transparency and information provision to users.

- Human oversight measures.

- High levels of accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity.

The United States (FDA and State Laws)

In the US, the FDA regulates AI as “Software as a Medical Device” (SaMD). The focus is heavily on safety and efficacy. Recent guidance emphasizes “Predetermined Change Control Plans,” allowing models to learn and adapt post-market within safe bounds. However, state-level privacy laws (like CCPA in California) and emerging liability laws are creating a patchwork of compliance requirements that providers must navigate.

Global Standards

Organizations like the WHO (World Health Organization) have released comprehensive guidance on the ethics of AI in health, emphasizing six core principles: protecting autonomy, promoting well-being, ensuring transparency, fostering responsibility, ensuring inclusiveness, and promoting responsive/sustainable AI.

9. Frameworks for Ethical Implementation

How do healthcare organizations move from abstract principles to practical implementation? Here are the frameworks currently considered best practice.

The Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Protocol

This framework dictates that for any high-stakes decision, a human must review and approve the automated suggestion.

- In Practice: An AI reads a mammogram and flags a suspicious mass. It does not issue a diagnosis. It routes the image to a radiologist with a “high priority” flag and a bounding box around the area of concern. The radiologist makes the final call.

The Ethics Committee for AI

Hospitals are increasingly establishing specific AI Ethics Committees, separate from standard Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). These committees include data scientists, clinicians, ethicists, and patient representatives. Their job is to vet new algorithms for bias, utility, and ethical congruence before they are purchased or deployed.

Continuous Algorithmic Auditing

Just as financial books are audited, AI models must undergo regular performance audits.

- Metric: Does the model perform equally well for men and women?

- Metric: Has the false positive rate increased since the last software update?

- Action: If a model fails an audit, it must be taken offline immediately (“kill switch” protocol).

10. Common Mistakes and Pitfalls

When implementing automated decision-making, organizations frequently fall into these ethical traps:

- Technological Solutionism: Believing that an app or algorithm can fix a structural social problem (e.g., trying to fix poor maternal health outcomes in minority communities solely with a monitoring app, without addressing the underlying lack of access to clinics).

- Failure to Validate Locally: Assuming a model trained at a top university hospital will work perfectly in a community clinic with different equipment and patient demographics.

- Ignoring the “Automation Paradox”: As systems become more reliable, humans become less attentive. When the system finally fails, the human is ill-equipped to step in because their skills have atrophied.

- Lack of Feedback Loops: Failing to provide a mechanism for clinicians to report when the AI is wrong. Without this feedback, the model never learns, and the clinicians stop trusting it.

11. Who This Is For (and Who It Isn’t)

This guide is for:

- Healthcare Administrators and CIOs: Who are purchasing or deploying AI tools and need to understand the liability and governance risks.

- Clinicians and Providers: Who are working alongside these tools and want to advocate for safe, ethical usage.

- Policy Makers: Who are drafting the rules of the road for medical AI.

- Patient Advocates: Who want to ensure technology serves the patient’s best interest.

This guide is NOT for:

- AI Engineers: Looking for technical code or mathematical formulas for loss functions (though the ethical concepts are relevant).

- Patients seeking medical advice: This is a governance guide, not a diagnostic tool.

Conclusion

Automating healthcare decisions offers a pathway to a future where medical care is more accurate, accessible, and efficient. However, this future is not guaranteed. Without a rigorous ethical framework, automation risks scaling bias, eroding privacy, and distancing the healer from the healed.

The ethical integration of AI in healthcare requires a shift in perspective. We must stop viewing AI as an oracle that delivers “truth” and start viewing it as a powerful, yet fallible, tool that requires constant supervision. The goal is not to replace the doctor, but to elevate the doctor-patient relationship by removing the burden of data processing, allowing the human aspects of care—empathy, judgment, and trust—to flourish.

Next Steps: If you are part of a healthcare organization exploring automation, your immediate next step should be to convene a multi-disciplinary stakeholder meeting—including patient representatives—to draft an “AI Bill of Rights” specifically for your institution, defining exactly how automated decisions will be governed, audited, and explained.

FAQs

Q: Can a patient refuse to have their diagnosis assisted by AI? A: In most jurisdictions, patients have the right to know if AI is being used significantly in their care and can request human-only review. However, as AI becomes embedded in standard software (like Electronic Health Records), completely opting out becomes difficult. Transparency and the right to human review are key components of emerging patient rights.

Q: Who is sued if an AI makes a wrong diagnosis? A: Currently, liability usually rests with the clinician, as they are the licensed professional responsible for the final decision (the “learned intermediary” doctrine). However, if the AI failed due to a product defect or negligence by the developer, the manufacturer could be liable. Legal standards are evolving rapidly in this area.

Q: How does automation affect doctor-patient confidentiality? A: Automation requires data sharing, often with third-party tech vendors. While Business Associate Agreements (BAAs) under HIPAA protect this data legally, the increased number of access points creates higher cybersecurity risks. Patients should be informed about who processes their data.

Q: What is “algorithmic bias” in healthcare? A: Algorithmic bias occurs when an AI system produces systematically unfair outcomes for certain groups of people. This often happens because the AI was trained on data that under-represented those groups, leading to less accurate diagnoses or treatment plans for minorities, women, or low-income patients.

Q: Is AI in healthcare regulated by the government? A: Yes. In the US, the FDA regulates medical AI that acts as a medical device. In the EU, the AI Act imposes strict regulations on high-risk medical AI. Other nations are developing similar frameworks. Compliance is mandatory, not optional.

Q: Can AI replace doctors? A: No, and certainly not in the near future. AI excels at specific tasks (like reading an X-ray or spotting a pattern), but it lacks the general intelligence, empathy, physical dexterity, and ethical judgment required for holistic medical care. The future is “Human + AI,” not “AI instead of Human.”

Q: What does “Human-in-the-Loop” mean? A: Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) means that an automated system cannot execute a high-stakes decision (like prescribing a drug or scheduling a surgery) without a qualified human reviewing and approving the action. It is a critical safety and ethical safeguard.

Q: How can we ensure AI is safe for patients? A: Safety is ensured through rigorous clinical validation (testing the model in real-world scenarios before release), continuous monitoring after deployment, external audits, and strict adherence to regulatory standards like those from the FDA or EU bodies.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029200

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2023). Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Enabled Medical Devices. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-aiml-enabled-medical-devices

- European Commission. (2024). The AI Act: High-risk AI systems. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai

- Obermeyer, Z., et al. (2019). Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 366(6464), 447-453.

- American Medical Association (AMA). (2023). Principles for Augmented Intelligence Development, Deployment, and Use.

- Topol, E. J. (2019). High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature Medicine, 25, 44–56.

- Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). (2023). Guidance on AI and data protection.

- National Academy of Medicine. (2019). Artificial Intelligence in Health Care: The Hope, the Hype, the Promise, the Peril.

- The Lancet Digital Health. (2024). Transparency and reproducibility in artificial intelligence.

- Coalition for Health AI (CHAI). (2023). Blueprint for Trustworthy AI in Healthcare. https://www.coalitionforhealthai.org/