The traditional paradigm of machine learning often resembles studying for a final exam: a model crams information from a massive, static dataset (training), takes the test (deployment), and then never opens a book again until the next scheduled update. In a world where data is static, this works perfectly. However, the real world is rarely static. Consumer behaviors shift overnight, stock markets fluctuate in milliseconds, and cybersecurity threats evolve faster than engineers can retrain static models.

Enter adaptive learning algorithms, often referred to in data science as online machine learning or incremental learning. These are the systems designed to “learn on the fly.” Instead of requiring a complete retraining cycle every time new data arrives, these algorithms update their parameters continuously as data streams in. They are the difference between a map printed in 2020 and a GPS navigation app that reroutes you based on traffic accidents happening right now.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore the architecture, mechanisms, and critical applications of adaptive learning algorithms. We will decode how they manage to stay relevant in dynamic environments, the specific challenges they face (such as concept drift and catastrophic forgetting), and how organizations are deploying them to create smarter, more responsive AI systems.

Scope Note: In this article, “adaptive learning” primarily refers to Online Machine Learning—algorithms that update continuously from data streams. While this technology powers “Adaptive Learning” in the educational technology (EdTech) sector (personalized curriculum), our focus here is on the broader underlying computational technology applicable across finance, IoT, logistics, and software.

Key Takeaways

- Continuous Updates: Unlike batch learning, adaptive algorithms update their internal models instantly as new data instances arrive, making them ideal for streaming environments.

- Concept Drift Management: These algorithms are essential for handling “concept drift”—the phenomenon where the statistical properties of the target variable change over time (e.g., changing fraud tactics).

- Efficiency: Adaptive learning often requires less memory and storage because it processes data sequentially and doesn’t necessarily need to store historical data forever.

- Stability vs. Plasticity: A core challenge is balancing the ability to learn new things (plasticity) without forgetting useful old information (stability).

- Broad Application: From predicting sensor failures in factories to personalizing TikTok feeds and detecting credit card fraud, adaptive algorithms drive modern real-time applications.

1. The Shift from Static (Batch) to Adaptive (Online) Learning

To understand why adaptive learning is revolutionary, we must first understand the limitations of the standard approach: Batch Learning.

The Batch Learning Bottleneck

In a typical batch learning workflow, data scientists gather a large dataset, clean it, train a model, validate it, and deploy it. This model is a snapshot of the world at the moment the data was collected. This approach suffers from two main issues:

- The Aging Model: As soon as the model is deployed, it begins to degrade. If you trained a housing price predictor in 2019, it would fail miserably in the 2021 market because the underlying economic relationships changed.

- Resource Intensity: Retraining a batch model usually implies retraining on the entire historical dataset plus the new data. As data grows, retraining becomes computationally expensive and slow, often taking days or weeks.

The Adaptive Solution

Adaptive learning algorithms process data sequentially. They ingest a single data point (or a small mini-batch), use it to update their internal weights, and then discard the raw data (optional, but common). This allows the model to evolve in real-time.

Comparison at a Glance:

| Feature | Batch Learning (Static) | Adaptive Learning (Online) |

| Data Processing | Processes all data at once. | Processes data sequentially (one by one or chunks). |

| Model Updates | Static after deployment; requires full retraining. | Continuous updates; evolves with every new input. |

| Computation Cost | High spikes during training; low during inference. | Constant, low-level computational load. |

| Storage Needs | Requires storing all historical training data. | Can discard data after learning; lower storage footprint. |

| Best Use Case | Stable environments (e.g., image recognition). | Dynamic environments (e.g., stock trading, weather). |

2. Mechanics: How Algorithms Learn on the Fly

How does a mathematical formula “learn” without stopping? The process relies on specific optimization techniques that differ from traditional methods.

The Online Loop

The workflow of an adaptive system generally follows this cycle:

- Receive: The system receives a new data instance (xt).

- Predict: The model makes a prediction (yt′) based on its current parameters.

- Reveal: The true label or outcome (yt) is revealed (sometimes immediately, sometimes with a delay).

- Loss Calculation: The algorithm calculates the error (loss) between its prediction (yt′) and the reality (yt).

- Update: The algorithm adjusts its internal parameters (weights) to minimize this specific error, usually via a method like Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD).

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)

In batch learning, gradient descent calculates the average error across the entire dataset before taking a step to adjust the model. In adaptive learning, Stochastic Gradient Descent allows the model to take a step after seeing just one example.

- Analogy: Imagine trying to find the lowest point in a valley (the optimal model). Batch learning looks at the entire landscape, calculates the perfect route, and takes a step. Adaptive learning (SGD) takes a step immediately based on the slope of the ground right under its feet. It might be “noisier” and wobble a bit, but it moves much faster and can adapt if the landscape (the data distribution) shifts while it is walking.

Specialized Algorithms

While deep learning models can be adapted for online learning, several classic algorithms are specifically designed for it:

- Hoeffding Trees: A variation of decision trees designed for massive data streams. It uses the Hoeffding bound to decide effectively when to split a node with high confidence using only a subset of data, rather than waiting for all data.

- Naive Bayes: Being a probabilistic classifier, Naive Bayes is easily updateable. When a new data point arrives, the algorithm simply updates the count of frequencies for features and classes.

- Online Convex Optimization: A framework used for problems like ad placement, where the system must select an action and receives a “reward” or “loss” immediately.

3. The Core Challenge: Concept Drift

The primary reason to use adaptive learning is Concept Drift. This occurs when the statistical properties of the target variable change over time. If a model does not adapt, its accuracy will plummet.

Types of Concept Drift

Understanding the “flavor” of change is crucial for tuning adaptive algorithms:

- Sudden Drift (Abrupt):

- Definition: The data distribution changes instantly.

- Example: A pandemic hits, and suddenly everyone buys masks and hand sanitizer. A retail demand model trained on 2019 data fails immediately.

- Gradual Drift:

- Definition: New concepts replace old ones slowly over time.

- Example: A gradual shift in fashion trends, where skinny jeans slowly lose popularity while wide-leg trousers gain traction over three years.

- Incremental Drift:

- Definition: A steady, continuous change.

- Example: Inflation slowly increasing the nominal price of goods over decades.

- Recurring Drift (Seasonality):

- Definition: Old concepts return periodically.

- Example: Winter coat sales spike every November. An adaptive model shouldn’t “unlearn” winter behavior during the summer; it should recognize the context has returned.

Detecting and reacting to drift

Adaptive algorithms use drift detection mechanisms (like ADWIN or Page-Hinkley tests) to monitor the model’s error rate.

- Passive Adaptation: The model constantly updates blindly. This works for gradual drift but might be slow for sudden drift.

- Active Detection: The system monitors error rates. If the error rate spikes significantly (triggering a drift alarm), the system might discard older history or increase the “learning rate” to adapt quickly to the new reality.

4. The Stability-Plasticity Dilemma & Catastrophic Forgetting

One of the most profound difficulties in adaptive learning is the Stability-Plasticity Dilemma.

- Plasticity: The ability to learn new data.

- Stability: The ability to retain old, valid knowledge.

If a model is too plastic, it suffers from Catastrophic Forgetting. This happens when training on new data completely overwrites the weights learned from old data. For example, a robot learning to climb stairs might forget how to walk on flat ground if the neural network updates too aggressively.

Solutions to Forgetting

- Rehearsal / Replay: The system keeps a small “buffer” or memory of diverse past examples and mixes them in with the new streaming data during updates. This reminds the model of what it learned previously.

- Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC): A technique used in neural networks that identifies which connections (weights) are most important for previous tasks and “freezes” or slows down changes to them, forcing the model to use other, less critical neurons for the new task.

- Ensemble Methods: Instead of one model changing, the system maintains a library of models. When the environment changes, it might spin up a new model for the new concept while keeping the old model archived in case that environment returns.

5. Real-World Applications

Adaptive learning is not theoretical; it runs the backend of many services we use daily.

1. Financial Fraud Detection

- Context: Financial transactions occur in massive streams. Fraudsters constantly invent new techniques (e.g., synthetic ID fraud, account takeovers).

- Adaptive Use: A static model trained on last month’s fraud patterns will miss today’s attack. Adaptive algorithms analyze streams of transaction data. If a new pattern emerges (e.g., high-value transactions from a specific IP range at 3 AM), the model learns this correlation instantly and begins flagging it, minimizing losses.

2. IoT and Predictive Maintenance

- Context: Manufacturing equipment is outfitted with sensors measuring vibration, temperature, and sound.

- Adaptive Use: Every machine is slightly different, and machines degrade slowly (incremental drift). An adaptive model deployed on the “edge” (directly on the machine) learns the specific baseline “normal” for that specific motor. As bearings wear down, the vibration patterns shift. The model adapts to the aging machine but flags deviations that indicate imminent failure, adjusting its threshold for “danger” as the machine ages.

3. E-Commerce and Recommendation Engines

- Context: User preferences are fickle. A user might be interested in camping gear today because of an upcoming trip, but will never look at a tent again after next week.

- Adaptive Use: Platforms like Netflix, TikTok, and Amazon use online learning to adjust recommendations instantly. If you click on three cat videos in a row, the algorithm updates your vector immediately to serve more cat content, rather than waiting for a nightly batch update.

4. Dynamic Pricing (Ride-sharing & Airlines)

- Context: The demand for rides or flights changes based on weather, local events, and time of day.

- Adaptive Use: Algorithms ingest real-time demand data (how many people are opening the app) and supply data (how many drivers are available) to adjust prices on the fly. This balances the marketplace dynamically.

6. Implementation Framework: Building an Adaptive Pipeline

Building an adaptive system requires different infrastructure than a standard batch system. It moves away from data warehouses (Snowflake/BigQuery) toward streaming buses (Kafka/Pulsar).

Step 1: The Streaming Architecture

You need a pipeline that can handle high-throughput data.

- Ingestion: Tools like Apache Kafka or Amazon Kinesis ingest data streams.

- Processing: Stream processing engines like Apache Flink or Spark Streaming handle the data manipulation in real-time.

Step 2: The Online Learner

You need a library that supports incremental updates. Standard Scikit-Learn libraries generally assume batch learning (with some exceptions like SGDClassifier using partial_fit).

- River (Python): River is the gold-standard Python library specifically for online machine learning. It merges functionality from older libraries like Creme and scikit-multiflow. It allows you to build pipelines where data flows through, updates the model, and yields predictions in one line of code.

- Vowpal Wabbit: A fast, out-of-core learning system developed by Microsoft Research and others, optimized for high-speed online learning and reinforcement learning.

Step 3: Evaluation (The Prequential Method)

You cannot use standard Cross-Validation in online learning because the order of data matters.

- Test-Then-Train: For every new data point, you first use the model to predict the outcome (Test). Then, you reveal the answer and update the model (Train).

- Running Metrics: You track accuracy or RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) as a moving average over time. This gives you a live “heartbeat” of model performance.

Step 4: The Fallback (Safety Net)

Never rely solely on an adaptive model without guardrails.

- Feedback Loops: Be careful of feedback loops. If an algorithm recommends only Action movies, the user only clicks Action movies, and the model thinks, “They love Action movies!” while the user is actually bored but has no other options.

- Canary Deployment: Often, a batch model is kept as a stable benchmark. The adaptive model runs in “shadow mode” until its stability is proven.

7. Ethical and Safety Considerations in Adaptive Systems

When models learn on the fly without human supervision, things can go wrong quickly.

The “Tay” Scenario

In 2016, Microsoft released a Twitter chatbot named Tay that learned from user interactions. Within 24 hours, users fed it toxic data, and the bot began outputting offensive, racist content. This is the dark side of “learning on the fly.”

- Lesson: Adaptive algorithms are highly susceptible to Data Poisoning. If bad actors know a model is updating in real-time, they can flood it with adversarial data to skew its decision boundary.

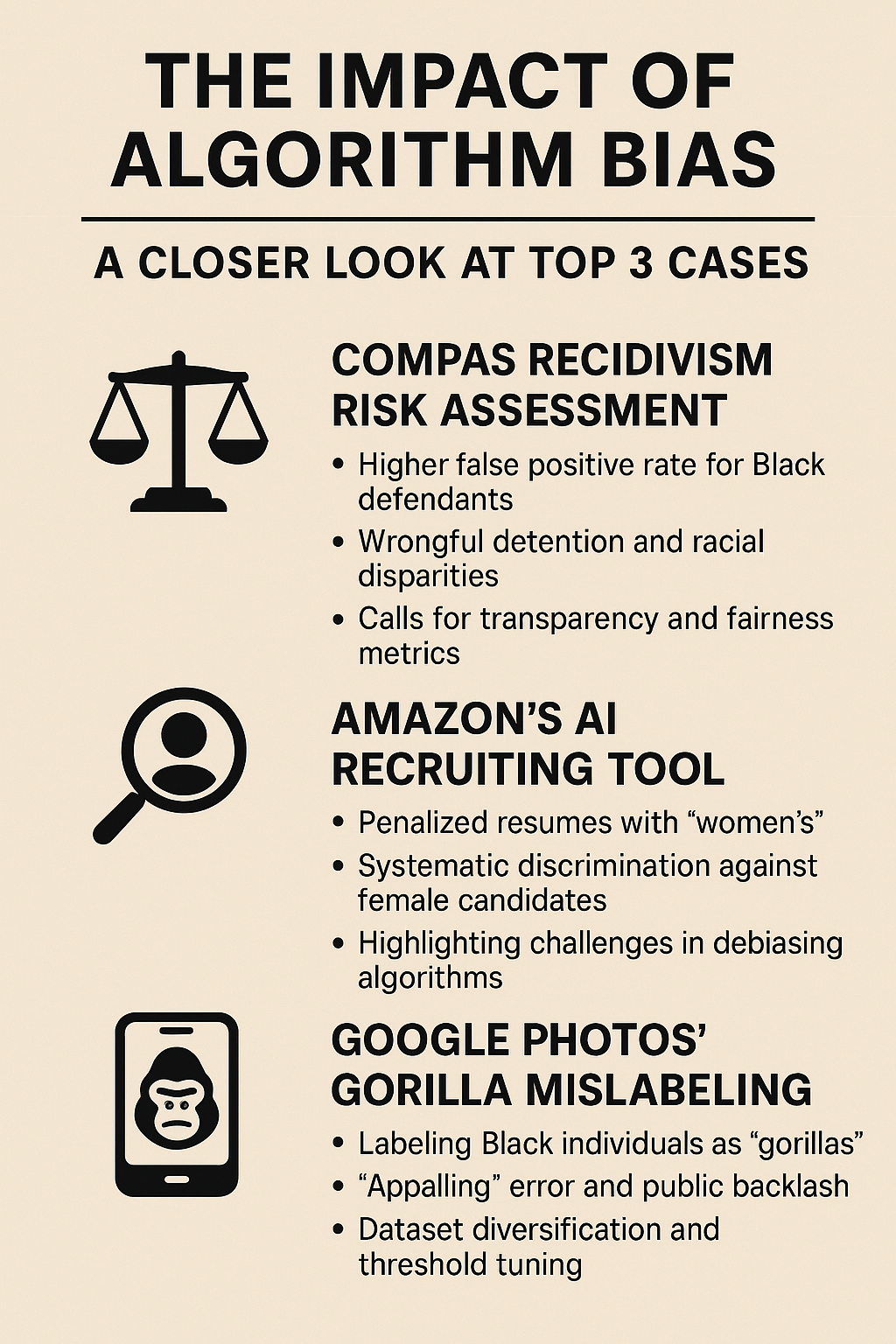

Managing Bias Amplification

If an adaptive hiring algorithm notices that it accepted a few candidates from a specific demographic who performed well, it might rapidly over-index on that demographic, rejecting qualified candidates from other groups before a human auditor notices.

- Mitigation: Real-time constraints must be hard-coded. For example, applying fairness constraints that prevent the model’s weights from drifting into discriminatory territories, regardless of the incoming data stream.

As of 2026: Regulation

As of January 2026, regulations like the EU AI Act place strict requirements on “high-risk” AI systems. Adaptive systems in high-risk categories (like credit scoring or biometrics) face higher scrutiny because their behavior is not fixed at the time of deployment. They require continuous monitoring logs to prove that the adaptation hasn’t violated compliance rules post-deployment.

8. Common Mistakes and Pitfalls

If you are planning to implement adaptive learning, avoid these frequent errors:

- Premature Optimization: Not every problem needs adaptive learning. If your data changes once a year, use batch learning. Adaptive learning adds significant engineering complexity.

- Ignoring Latency: The update step takes time. If your inference requirement is sub-millisecond (e.g., high-frequency trading), the time taken to run backpropagation for every single data point might be too high. You may need to update in mini-batches (e.g., every 100 points) rather than truly one-by-one.

- Lack of versioning: In batch learning, you have “Model v1.0”. In adaptive learning, the model at 12:00 PM is different from the model at 12:05 PM. Reproducing bugs becomes a nightmare. You must log the data stream sequence exactly to reproduce the state of the model.

9. Future Trends: Where Adaptive Learning is Going

The future of adaptive algorithms lies in their intersection with hardware and privacy.

Federated Learning

This is a decentralized form of adaptive learning. Instead of sending data to a central cloud to update a model, the learning happens on the device (edge). Millions of smartphones update their local models (e.g., predictive text) and send only the weight updates (not the data) to the central server. This allows for global adaptive learning while preserving user privacy.

Neuromorphic Computing

New chip architectures (like Intel’s Loihi) mimic the human brain’s spiking neural networks. These chips are designed specifically for continuous, low-power learning, enabling devices like drones or cameras to learn on the fly with minimal energy consumption.

Self-Supervised Streams

Currently, most adaptive learning requires “labels” (we need to know if the fraud prediction was right to update the model). Future algorithms will rely more on self-supervised learning, where the model generates its own supervisory signals from the structure of the data stream itself, reducing the reliance on immediate human labeling.

Conclusion

Adaptive learning algorithms represent the shift from static software to organic, evolving intelligence. In a world characterized by volatility and speed, the ability to “learn on the fly” is no longer a luxury—it is a necessity for staying competitive.

For organizations looking to adopt these systems, the journey begins with identifying the right use case—where data is fast, drift is high, and the cost of being wrong is substantial. From there, it requires a robust engineering mindset that prioritizes monitoring and safety just as much as accuracy.

Next Steps: If you are a data scientist or engineer looking to experiment with these concepts, start by exploring the River library in Python. Try simulating a data stream with a known concept drift and observe how a Hoeffding Tree adapts compared to a static Random Forest. Seeing the “accuracy recovery” curve in real-time is the best way to understand the power of adaptive learning.

FAQs

1. What is the difference between online machine learning and adaptive learning? In the context of data science, they are often used interchangeably. “Online machine learning” refers to the technical method of processing data sequentially (one by one). “Adaptive learning” describes the capability of the system to adjust to new environments. However, be aware that in the education sector, “Adaptive Learning” specifically refers to software that personalizes lesson plans for students.

2. Can deep learning models learn on the fly? Yes, but it is challenging. Deep learning models (neural networks) typically require large batches of data to calculate stable gradients. Updating a neural network with a single data point can cause the weights to oscillate wildly (noisy gradients). However, techniques like “Experience Replay” and “Elastic Weight Consolidation” are making online deep learning more stable.

3. What happens if the data stream contains bad or noisy data? This is a major risk. Since the model updates immediately, noise can degrade performance. To mitigate this, systems use “learning rates” (determining how much influence new data has). A lower learning rate makes the model more robust to noise but slower to adapt to real changes. Robust outlier detection is also essential before the data hits the learning algorithm.

4. Is adaptive learning more expensive than batch learning? It depends on the metric. It is usually computationally cheaper because you process data once and don’t need to retrain on terabytes of history repeatedly. However, it is architecturally more expensive because building reliable streaming pipelines and monitoring infrastructure is more complex than running a batch script.

5. How do you label data in real-time for adaptive learning? This is the biggest bottleneck. For some tasks (like predicting the next click), the label arrives instantly (the user clicked or didn’t). For others (like predicting loan default), the label arrives months later. Adaptive learning works best for “short feedback loop” problems. If delays are long, you may need a hybrid approach or rely on unsupervised adaptation.

6. What are the best tools for adaptive learning? For Python users, River is the leading library. For big data distributed processing, Apache Flink combined with Alink or Spark Streaming offers online learning capabilities. Vowpal Wabbit is industry-standard for high-performance scenarios.

7. Does adaptive learning eliminate the need for data scientists? No. It shifts the data scientist’s role. Instead of spending time manually retraining models, the data scientist focuses on designing the monitoring architecture, defining the drift detection thresholds, and ensuring the safety rails are holding. The human moves from being the “trainer” to being the “supervisor.”

8. Can adaptive learning handle seasonality? Yes, but it needs help. A basic adaptive model might “forget” summer trends during the winter. To handle seasonality, feature engineering is crucial (e.g., adding “day of year” as a feature) or using ensemble methods that keep different models for different seasons.

References

- River Development Team. (2024). River: Online Machine Learning in Python. River Project Documentation. https://riverml.xyz/

- Gama, J., Žliobaitė, I., Bifet, A., Pechenizkiy, M., & Bouchachia, A. (2014). A Survey on Concept Drift Adaptation. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR).

- Huyen, C. (2022). Designing Machine Learning Systems: An Iterative Process for Production-Ready Applications. O’Reilly Media. (Chapter on Continual Learning).

- Microsoft Research. (n.d.). Vowpal Wabbit: Fast, efficient, and flexible online learning. Vowpal Wabbit Project. https://vowpalwabbit.org/

- European Parliament. (2024). The EU Artificial Intelligence Act: Regulation on European Approach for AI. Official Journal of the European Union.

- Bifet, A., & Gavalda, R. (2007). Learning from Time-Changing Data with Adaptive Windowing. SIAM International Conference on Data Mining.

- Kirkpatrick, J., et al. (2017). Overcoming catastrophic forgetting in neural networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). DeepMind.