If you’re comparing a DAO vs decentralized protocols, you’re really weighing social governance models against technical control surfaces. A decentralized autonomous organization (DAO) coordinates people and capital using rules enforced by smart contracts, while a decentralized protocol embeds those rules directly in code and consensus—sometimes with minimal ongoing human discretion. In one sentence: a DAO is a decision-making layer; a decentralized protocol is an execution layer you can (and should) govern sparingly. To choose wisely, evaluate risk tolerance, speed of change, accountability, and how much authority you want humans—versus code—to hold. The short path: (1) define outcomes, (2) map decisions to code vs community, (3) pick a voting or council model only where needed, (4) add timelocks and emergency stops, (5) minimize governance over time for stability.

Disclaimer: The following is educational and not legal, financial, or security advice. Consult qualified professionals before implementing governance or technical controls.

1. Start With the Boundary: What Must Humans Decide vs What Code Should Enforce

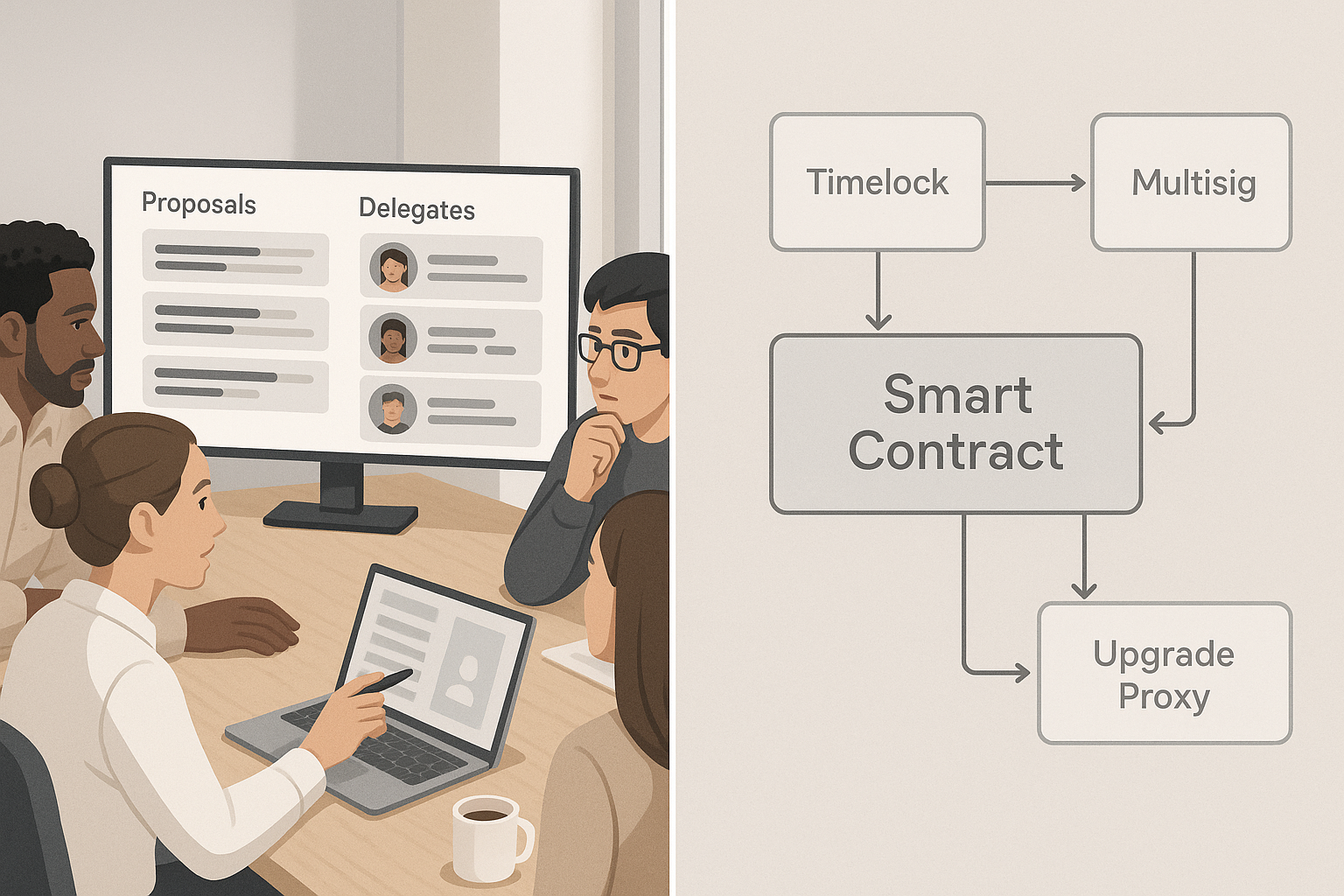

The fastest way to resolve DAO vs decentralized protocols is to draw a bright boundary between decisions that require judgment and those that should be hard-coded. Most projects benefit from a thin human layer—budgeting, selecting stewards, or changing high-level policy—and a thicker code layer for deterministic, recurring operations. Begin by listing decisions you expect to make repeatedly (e.g., parameter tuning, feature flags) and those you hope to “set and forget.” If you can define an objective metric and a safe range, the protocol should enforce it; if context or values matter, a DAO (or a council) should decide. This framing reduces governance bloat, narrows attack surface, and improves user trust because fewer behaviors depend on sentiment or turnout. Close the loop by clarifying who can propose changes, who can execute them, and how the system recovers from mistakes (timelocks, rollbacks, and pauses). This boundary-first approach becomes your blueprint for both social processes and smart-contract architecture. A concise definition of DAOs from the Ethereum documentation reinforces this division of concerns: DAOs coordinate people; smart contracts enforce the rules they vote in.

How to do it

- Inventory decisions for the next 6–12 months; classify each as value-laden (human) or mechanical (code).

- For mechanical items, specify invariant checks and safe parameter ranges.

- For value-laden items, choose a governance method (token vote, delegated council, or both).

- Document who can propose, queue, and execute each change.

- Add recovery mechanisms: timelocks, pause/kill switches, and rollbacks.

Numbers & guardrails

- Aim to put >70% of recurring actions behind automated checks and only <30% through governance proposals (rule of thumb for early stages).

- For code-executed actions, require a timelock delay (e.g., 48–96 hours) before execution to allow audit and user exit. OpenZeppelin’s timelock modules formalize this pattern.

Synthesis: Decide the boundary first; it prevents over-governance and keeps your protocol predictable while reserving judgment for the proposals that truly need it.

2. Token Voting Is Not the Only Option: Match Mechanism to Risk and Values

Many teams default to one-token-one-vote because it’s familiar, but you should select a voting mechanism that mirrors your risks and goals. Token voting is simple and liquid, yet it can concentrate power and invite vote buying; quadratic or square-root voting can temper plutocracy by pricing influence nonlinearly; delegation can improve participation by routing power to active specialists; conviction voting smooths decisions over time; futarchy uses markets to forecast outcomes, and multisig/council models trade breadth for speed and accountability. In practice, projects blend mechanisms: delegation plus on-chain votes for major changes, Snapshot (off-chain) for signaling, and a small security council for emergencies. Critiques by Vitalik Buterin and others remind us that coin-voting alone is fragile; your mechanism should address collusion, apathy, and information asymmetry rather than assume them away. When evaluating, consider Sybil resistance, the cost to participate, and whether influence should be transferable, reputation-based, or earned. The goal is not maximal democracy; it’s fit-for-purpose legitimacy.

Tools/Examples

- Compound/Bravo for on-chain proposals with thresholds, quorum, and timelock.

- Snapshot for gasless signaling votes and custom strategies.

Numbers & guardrails

- Use a proposal threshold (e.g., fixed voting power) and quorum to deter spam. Compound’s defaults illustrate a rigorous timeline: proposal threshold, days-long voting period, then timelock delay.

- For quadratic/square-root voting pilots, start with caps on purchasable votes and identity constraints to limit sybils, then evaluate variance in outcomes across 3–5 proposals. SSRN

Synthesis: Mechanisms are instruments; choose the one that mitigates your specific risks rather than copying whatever is trendy.

3. Practice Governance Minimization: Shrink the Social Attack Surface

Governance minimization says: govern only what you must, then reduce it over time. Protocols that rely heavily on human votes for routine changes invite capture, coordination failures, and investor-driven politics. A better path is to hard-code invariants, automate parameter adjustments where safe, and reserve governance for exceptional events. This principle builds credibility with users who prefer systems that don’t change capriciously. Essays from founders and researchers argue that protocols become dependable standards when they avoid frequent discretionary governance—just like internet protocols did. Operationally, commit in writing to a narrow “governance surface area,” adopt timelocks so users can react to approved changes, and publish deprecation schedules for powers you plan to sunset. Over time, upgrade hooks can be locked, emergency levers handed to diverse councils with clear mandates, and policy parameters bounded by code. Governance minimization doesn’t eliminate community voice; it channels it toward durable norms and limited, high-impact choices that actually need human judgment.

Common mistakes

- Treating every small parameter change as a vote.

- Letting emergency powers become permanent “shortcuts.”

- Vague scopes for councils or committees.

Numbers & guardrails

- Publish a retirement plan for powers: e.g., remove or narrow at least one governance permission per release until only critical controls remain.

- Ensure timelock coverage for any function that can move treasury funds or change core logic.

Synthesis: The less you ask people to vote on, the more your protocol behaves like a stable utility—and the harder it is to capture.

4. On-Chain vs Off-Chain Voting: Choose Speed, Cost, and Finality Deliberately

On-chain governance (e.g., OpenZeppelin Governor, Compound Bravo) provides cryptographic finality: proposals execute through contracts after quorum and timelock. Off-chain votes (e.g., Snapshot) are fast and gasless, good for gauging sentiment or iterating policy drafts. Off-chain results are typically advisory unless a binding bridge exists; many DAOs use Snapshot for initial signaling, then escalate important proposals on-chain. The trade-offs are clear: on-chain is slower and costlier but enforceable; off-chain is cheap and flexible but requires trust in tallying and execution agents. A pragmatic pattern is to bind off-chain votes via multisig policies: the council commits to execute any Snapshot result that meets documented criteria (quorum, supermajority, no emergency flags). Some projects also integrate custom voting power strategies—staked balances, time-weighted holdings, or reputation scores—to align incentives. Your choice should reflect participation goals, treasury risk, and upgrade cadence. If you expect rapid iterations or frequent parameter updates, stage them through off-chain signaling with periodic on-chain batched execution windows.

How to do it

- Define which proposal classes must go on-chain (treasury moves, contract upgrades).

- Use Snapshot for policy drafts, grants, and temperature checks; document quorum and majority rules.

- Bridge off-chain results via a multisig that signs transactions queued in a TimelockController.

Mini case

- A grants DAO uses Snapshot with a 10% quorum and simple majority to approve grants, then a 3-of-5 multisig queues payments into a 72-hour timelock before disbursing, aligning speed with safety. (Timelock pattern per OpenZeppelin Governor.)

Synthesis: Use off-chain to move fast and learn; require on-chain for anything that changes rights, risks, or core logic.

5. Delegation and Representation: Power the System With Active Stewards

Delegation channels passive holders’ influence to active stewards who research, vote, and report. It’s essential wherever voter apathy or gas costs depress participation. Effective programs make delegation explicit and revocable; they publish delegate manifests, voting histories, and conflict disclosures; and they pay stipends conditioned on transparency and attendance. Projects like Uniswap embed delegation natively so stakeholders can assign votes without transferring tokens, while community tools track delegates’ performance across proposals. Where specialized expertise matters, consider domain councils (risk, growth, security) with explicit charters and check-ins. Hybrid designs pair broad token votes with advisory delegates who can initiate proposals and recommend options but can’t unilaterally execute changes. This keeps decision power with the community while ensuring that informed proposals reach the ballot. Over time, rotate or term-limit delegates to avoid entrenchment and publish a clear recall process.

Mini-checklist

- Public delegate directory with mandates and addresses.

- Transparent compensation, if any, tied to activity.

- Quarterly review: replace inactive delegates.

Tools/Examples

- On-chain delegation in Uniswap’s governance contracts and user guides. Uniswap Docs

Synthesis: Delegation converts passive supply into informed, accountable influence—without surrendering community control.

6. Emergency Controls: Timelocks, Pause Guardians, and Security Councils

Exceptional powers deserve exceptional process. Timelocks create notice windows so communities can audit and exit before changes execute; pause guardians (or circuit breakers) can stop dangerous functions fast; security councils provide trained responders who can approve emergency actions within strict bounds. Together, these tools address the reality that exploits, misconfigurations, and governance attacks do occur. Implement timelocks on any administrative function that moves funds or upgrades contracts. Define narrowly scoped pause permissions (e.g., pausing mint/borrow but not withdraw) and require multi-signature approval from diverse actors. Document what triggers a pause, who can unpause, and the maximum pause duration. Security council runbooks should specify incident triage, upgrade workflows, and communication timelines. Several audits and vendor guides recommend drills and time-boxed actions (e.g., pausing within minutes, reviewing fixes within days), balancing swift mitigation with accountability and later community ratification.

Numbers & guardrails

- Multisig threshold: ≥60% of signers for emergency actions; require geographic and organizational diversity.

- Timelock delay: 48–96 hours for routine upgrades; longer for high-risk changes.

- Pause scope: isolate risky functions; Compound’s pause guardian model is a reference pattern.

Tools/Examples

- OpenZeppelin Pausable and TimelockController modules; incident-response guidance and security-council best practices.

Synthesis: Emergencies are governance too—codify them so the fastest actions are also the most legitimate.

7. Upgradeability & Change Management: Proxies, Queues, and Rollouts

Most modern protocols separate interfaces from implementations using proxy patterns, allowing upgrades without changing addresses. Governance then controls which implementation the proxy points to. To keep this safe, route upgrade calls through a timelock owned by governance (or a council), batch related changes, and publish pre- and post-conditions users can verify. Specify who can deploy candidate implementations, which tests must pass, and how you’ll roll back if monitoring trips alarms. For multi-chain deployments, pick a canonical chain for governance and pass messages (or execute mirrored proposals) to satellite chains, ensuring timelock parity across instances. Compound’s governance docs outline how the timelock administers instances and how parameter changes propagate via configurators; similar modular designs keep upgrades auditable and reversible. The net effect is predictable change with verifiable provenance—exactly what risk-averse users want from core infrastructure.

Numbers & guardrails

- Require at least N+1 independent reviews (e.g., core team, auditor, external reviewer) before queueing.

- Set a minimum observation window (e.g., 24 hours on testnet, 48–72 hours on mainnet timelock) before execution.

- For multi-chain, enforce symmetric delays so no chain can be upgraded faster than the canonical chain. docs.compound.finance

Mini-checklist

- Proxy change diff published.

- Upgrade scripts open-sourced.

- Rollback path documented and tested.

Synthesis: Upgrades should feel boring—scripted, delayed, and fully inspectable—so users can trust the system while it evolves.

8. Treasury & Resource Allocation: DAO Budgets vs Protocol Fee Switches

Treasuries are where DAOs shine: community-directed grants, contributor pay, audits, liquidity programs, or public goods. Protocols, by contrast, should rarely “decide to spend” at runtime; they should emit fees according to clear rules with minimal discretion. Keep the two layers distinct: use your DAO to set strategy and budgets, then stream funds via contracts that enforce vesting, cliffs, and accountability milestones. For routine disbursements, a committee or multisig can execute within a budget approved by token holders, subject to regular reporting and revocation rights. When discussions get contentious, off-chain signaling helps converge on scope before any on-chain commitment. The guiding principle is clarity: token holders decide what outcomes to fund; contracts ensure how funds move remains predictable and reversible where necessary.

How to do it

- Publish a rolling treasury plan with capped categories (e.g., audits, growth, ops) and objective KPIs.

- Use payment streams with emergency halt conditions.

- Require post-grant reports and clawback hooks for non-delivery.

Mini case (numbers)

- Annual budget: 1,000,000 units native token. Allocate 30% audits, 25% grants, 20% liquidity, 15% ops, 10% R&D. Disburse via monthly streams with 7-day halts for material breaches; reports due quarterly. (Structure mirrors common practice; implementation should be encoded in contracts with timelocks.)

Synthesis: Let the DAO decide why and what to fund; let the protocol’s contracts decide how money moves, with baked-in accountability.

9. Legal & Accountability: Entity Choices, Liability, and Jurisdictions

Governance involves people, and people exist within legal systems. Token-voting communities that act collectively may be treated as unincorporated associations or partnerships in some jurisdictions, exposing members or voters to liability. Cases and commentary highlight that regulators and courts are still shaping how DAOs fit into existing categories, while some regions now offer DAO-native entities to provide limited liability. Your key choices are whether to form an entity (e.g., a foundation, association, or LLC-style wrapper), how that entity relates to your token holders and multisigs, and what disclosures or policies you’ll publish to clarify roles. If your protocol touches regulated activities (e.g., lending, derivatives, payments), consult counsel early; emergency powers and pause mechanisms can also intersect with consumer protection expectations. The legal landscape is evolving; prudence means separating protocol operation (automated, transparent) from discretionary programs run by a legal entity, with clear terms and privacy practices.

Region-specific notes

- Some jurisdictions recognize DAOs as legal entities; others treat them as partnerships or ignore them altogether.

- Publishing a charter, conflict-of-interest policy, and disclosures reduces ambiguity even where formal law is unsettled.

Mini-checklist

- Map roles: token holders, delegates, council, multisig signers, service providers.

- Determine entity wrappers for treasury and payroll.

- Establish incident-response and disclosure policies in plain language.

Synthesis: Clarity of roles and a sensible wrapper can protect contributors without undermining decentralization.

10. Participation, Sybils & Turnout: Design for Real-World Human Behavior

A persistent challenge in token governance is low, uneven participation and the ease with which influence can be bought, borrowed, or coordinated off-chain. Empirical work shows voting is often centralized among a small group, turnout is sensitive to participation costs, and voting rights are transferable in ways that may undermine long-term security. This doesn’t mean token voting is hopeless; it means incentives and UX matter. Reduce friction with gasless voting (off-chain), standardize proposal formats, and publish “explainer” memos. Consider reputation overlays, minimum stake-time requirements, and delegation marketplaces that emphasize alignment rather than popularity. Where the protocol’s safety is at stake, pair votes with risk reviews and “cooling-off” delays. Finally, measure what matters: not just how many wallets voted, but how informed those votes were and how well outcomes matched stated objectives.

How to do it

- Use off-chain signaling (Snapshot) to reduce cost barriers; bind results via documented policies.

- Build a lightweight “why it matters” template for proposals; require risk and security sections.

- Pilot identity or stake-time requirements where sybil risk is high.

Mini case (numbers)

- Moving from on-chain only to a Snapshot-first flow with delegates: proposal participation rises from hundreds to thousands of votes per proposal; delegate coverage targets >60% of circulating voting power within one quarter through campaigns and reporting. (Illustrative targets; set your own based on supply and community size.)

Synthesis: Optimize for informed, low-friction participation and measure it—what you track improves.

11. Risk Controls in Practice: From Pause to Recovery and Post-Mortems

Risk controls are only as good as the runbooks behind them. Define trigger conditions (oracle failure, invariant breach, abnormal outflows), roles (who can pause, who must co-sign), and time boxes (how fast to act and how long a pause can last without ratification). During an incident, your council should follow a checklist: pause scoped functions, communicate publicly, craft a patch, stage it behind a timelock where possible, and schedule a ratification vote. After recovery, publish a post-mortem with fixes, timelines, and compensation decisions if applicable. Industry patterns show pause guardians held by community multisigs, upgrades batched with audits, and security councils empowered to act within narrow limits. Documenting these pathways before trouble hits is both a technical and a governance task—and it’s central to user trust.

Numbers & guardrails

- Pause window: initial pause within minutes, review within 48 hours, community ratification within a set window afterward.

- Veto or override limits: any unilateral emergency action expires unless confirmed by governance, and all logs must be published. (Patterns drawn from public incident-response guides.) openzeppelin.com

Mini-checklist

- Pre-approved emergency signers with hardware keys.

- Dry-run drills on testnets.

- Public status page and incident timeline template.

Synthesis: Bake response and accountability into your design so emergencies strengthen—not weaken—legitimacy.

12. A Practical Decision Framework: When to Use a DAO vs a Decentralized Protocol

The final step is making the call. Use this compact matrix to align your architecture with your goals:

| Decision area | Prefer a DAO (social) | Prefer protocol (technical) |

|---|---|---|

| Budgeting & grants | Community votes, delegate committees | Streaming contracts with milestones |

| Core logic | Advisory votes only | Hard-coded invariants; guarded upgrades |

| Parameters | Delegate-led proposals for major shifts | Auto-adjust within safe ranges |

| Upgrades | On-chain vote + timelock | Proxy pattern; audits; rollbacks |

| Emergencies | Security council ratifies | Pausable functions; scoped stops |

| Participation | Delegation & Snapshot | Gasless signaling; execution bridges |

How to do it

- Write a one-page constitution that binds your DAO to minimal discretion and codified safety rails.

- For each proposal type, specify who proposes, how votes count, what executes, and what delays apply.

- Adopt an opinionated governance stack: OpenZeppelin Governor + Timelock on-chain, Snapshot off-chain, Safe multisig for execution, and a narrowly scoped security council for emergencies.

Numbers & guardrails

- Quorum bands: start conservative (e.g., 5–15%) and revisit after 5–10 proposals; use higher thresholds for irreversible changes (treasury drains, logic upgrades). Compound’s governance shows how thresholds, voting periods, and timelocks compose a predictable workflow.

Synthesis: Codify a thin, high-legitimacy human layer atop a thick, predictable technical layer; that’s the sweet spot for durable systems.

Conclusion

Choosing between a DAO vs decentralized protocols isn’t binary; it’s a layering decision. Let code do the heavy lifting—enforcing invariants, rate limits, and upgrade workflows—while the community decides values and strategy within a tightly scoped surface area. Start by drawing the boundary between human judgment and machine enforcement, then choose the lightest governance mechanism that can credibly handle the remaining choices. Pair on-chain finality with off-chain speed, and surround everything with timelocks, pause guardians, and a disciplined incident-response plan. Measure participation and fairness, minimize governance over time, and keep your users informed with transparent documentation and post-mortems. If you apply these 12 lenses, you won’t just pick the right model; you’ll build a system that is safer, clearer, and easier to trust. Ready to decide? Draft your boundary document and governance surface map today.

FAQs

1) What’s the simplest definition of a DAO vs a decentralized protocol?

A DAO is a community-run organization that decides; a decentralized protocol is code that executes. DAOs aggregate preferences through governance processes, while protocols apply deterministic rules. In healthy systems, governance sets high-level policy and the protocol enforces it through smart contracts. For more formal definitions, see the Ethereum documentation and leading governance frameworks.

2) Do I need both a DAO and a protocol?

Often yes. Most products pair a minimal DAO—handling budgets, delegates, and upgrades—with a protocol that automates day-to-day operations. The DAO’s scope should shrink over time (governance minimization) as code matures and risks are better understood.

3) Is token voting good enough?

Sometimes, but don’t rely on it blindly. Token voting can centralize power, enable vote buying, and depress participation when costs are high. Consider delegation, quadratic or square-root voting, or council models where appropriate, and use gasless signaling to widen participation.

4) When should I use off-chain voting like Snapshot?

Use it when you need speed, exploration, or broad sentiment without gas costs—draft policies, grants, or temperature checks. Bind results through a documented policy and execute on-chain for anything that changes rights or risk.

5) How do timelocks actually protect users?

Timelocks create a delay between approval and execution, giving users, auditors, and integrators time to review and react—exiting or raising alarms if needed. They’re a standard part of secure governance stacks and are supported by popular libraries.

6) What is a pause guardian or circuit breaker?

It’s an authorized role (often a multisig) that can pause specific protocol functions during emergencies. The scope should be narrow, with clear triggers and quick community ratification. Many DeFi protocols use this pattern to buy time during incidents.

7) What’s conviction voting, in plain terms?

Instead of a one-time yay/nay, conviction voting lets stakeholders stake support on proposals; support accumulates over time until a threshold is met. It reduces short-term swings and amplifies consistent preferences. Implementations exist in open-source tooling and research repos.

8) Are there market-based alternatives to voting?

Yes—futarchy: communities vote on values and bet on which policies will achieve them, using prediction markets to guide decisions. It’s experimental but useful to understand as part of your option set.

9) How can we avoid governance capture by a few big holders?

Blend mechanisms (delegation + quadratic/square-root weighting), set proposal thresholds and quorums, and publish transparent conflict policies. Consider non-transferable reputation for certain domains and higher thresholds for irreversible actions. Research and practitioner guides discuss these trade-offs.

10) What metrics prove our governance is healthy?

Track quorum attainment rate, median voter turnout, delegate coverage of voting power, proposal lead time, timelock adherence, and incident-response SLAs. Also measure how often outcomes match documented goals. Studies emphasize participation quality and concentration—not just raw counts. arXiv

11) Do we need a legal entity for the DAO?

If you’re paying people, signing contracts, or bearing risk, a wrapper entity often helps with liability and operations. Laws vary; some places recognize DAOs as entities, while elsewhere token voters can be treated as partners. Get counsel early.

12) What’s a realistic first-month rollout plan?

Ship with a minimal DAO (delegation enabled), Snapshot for signaling, a Safe multisig executing through a Timelock, and clearly scoped pause powers. Publish your boundary document and proposal types, then run drills and refine thresholds after your first 3–5 proposals.

References

- “What is a DAO?” — Ethereum.org (web), https://ethereum.org/dao/

- Ehrsam, F., “Governance Minimization” — fehrsam.xyz (blog), https://www.fehrsam.xyz/blog/governance-minimization

- Buterin, V., “Moving beyond coin voting governance” — vitalik.eth.limo (blog), https://vitalik.eth.limo/general/2021/08/16/voting3.html

- Posner, E.A. & Weyl, E.G., “Quadratic Voting as Efficient Corporate Governance” — University of Chicago (paper), https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics/643/

- 1Hive, “Conviction Voting (code & models)” — GitHub, https://github.com/1Hive/conviction-voting-app and https://github.com/1Hive/conviction-voting-cadcad

- Hanson, R., “Shall We Vote on Values, But Bet on Beliefs?” — GMU (paper), https://mason.gmu.edu/~rhanson/futarchy2013.pdf

- OpenZeppelin, “Governor & Timelock” — Docs, https://docs.openzeppelin.com/contracts/5.x/api/governance

- Compound, “Governance (Governor Bravo)” — Docs, https://compound.finance/docs/governance

- Snapshot, “Welcome to Snapshot docs” — Docs, https://docs.snapshot.box/

- Gauntlet, “Guide to Protocol Risk Controls” — gauntlet.xyz (guide), https://www.gauntlet.xyz/resources/guide-to-protocol-risk-controls

- OpenZeppelin, “Pausable” — Docs, https://docs.openzeppelin.com/contracts/4.x/api/security

- Reuters, “Digital assets and DAOs: new theories of liability” — reuters.com (analysis), https://www.reuters.com/legal/legalindustry/digital-assets-daos-new-theories-liability-2024-06-10/